| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Unlike other countries, we have not developed coherent national science policies. Indeed, the very idea is abhorrent to many.Our free enterprise laissez-faire system has served us well during periods of expansion and growth, but in retrenchment the development of more formal scienceand technology policies seems essential if we are to preserve the best aspects of our system.

—D. Allan Bromley, 1982

I will upgrade the President’s science advisor to Assistant to the President and make him an active member of the EconomicPolicy Council and our national security planning processes. And I will create a President’s Council of Science and Technology Advisors, composed of leadingscientists, engineers and distinguished executives from the private sector.

—George H.W. Bush, October 1988

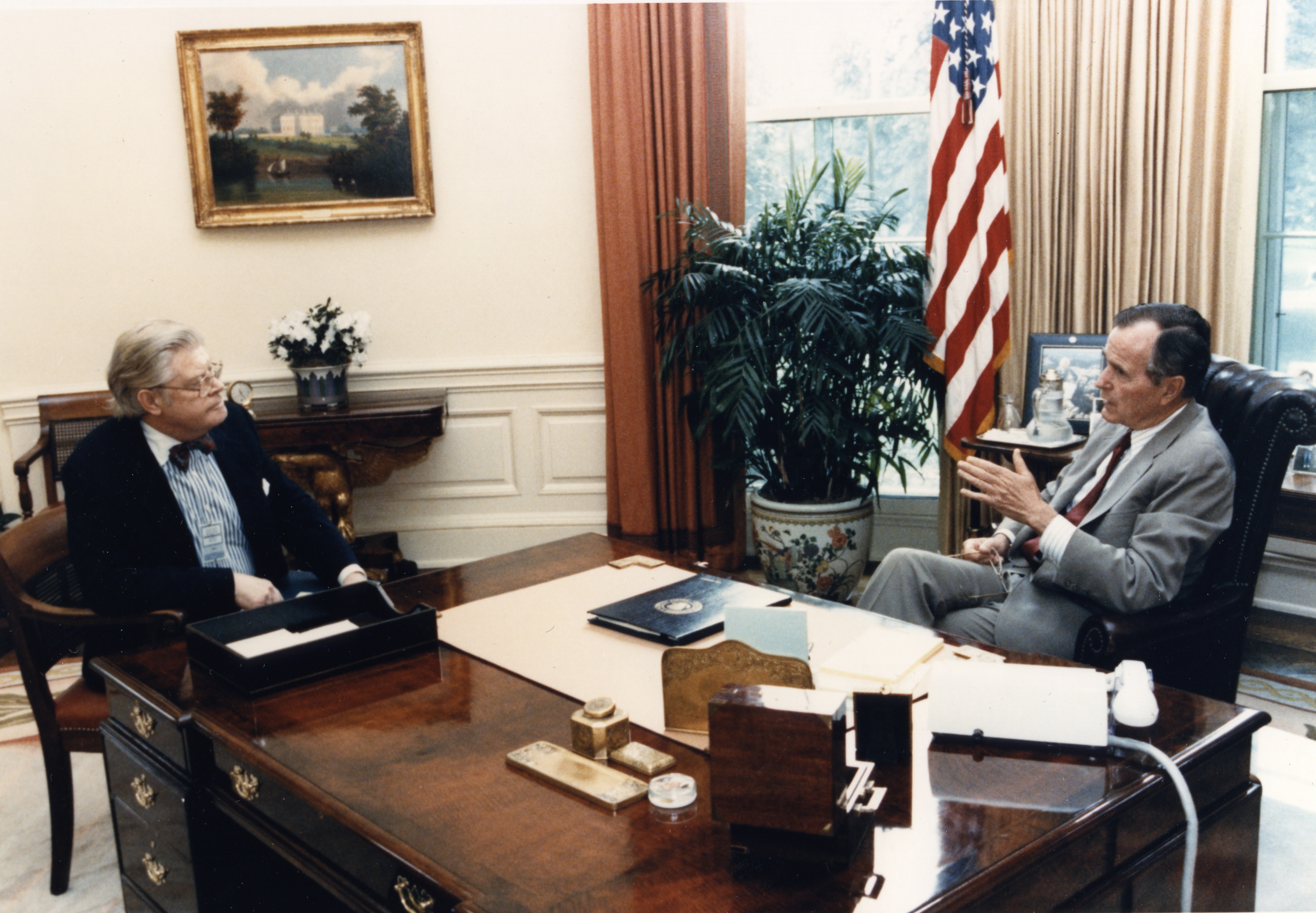

During the 1988 presidential campaign, Vice President George H.W. Bush had a science adviser: D. Allan Bromley, Professor ofPhysics at Yale and a charter member of the White House Science Council. Jeffrey Mervis, “Science and the Next President,” The Scientist (June 27, 1988). Upon his election, Bush nominated Bromley as Assistant to the President for Science and Technology and director of the OSTP. Bromley was the first science advisor to hold the title Assistant to the President for Science and Technology. Both of Clinton’ssuccessive science advisors had that title, as does the science advisor to President Barack Obama. The Senate unanimously confirmed him in the latter position on August 4; confirmation was not required for the former.

Bromley brought a significant roster of accomplishments along with him. Soon after arriving as associate professor ofphysics at Yale in 1960, he managed to obtain federal funding for a state of the art tandem Van de Graff particle accelerator, with construction of the facilityitself funded by the university. While at Yale, he made many advances in nuclear physics, and was awarded the National Medal of Science in 1988. He was alsoelected to the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

During the Carter and Reagan administrations, Congress had expressed increasing frustration with the failure of eitherpresident to implement significant features of the OSTP Act.

For example, although the Ford administration had created the Act’s mandated President’s Council on Science and Technology,the Carter administration never convened the PCST, nor did it ever fulfill its promise to conduct the congressionally mandated two-year survey of the federalgovernment’s science and technology programs. By the end of the Reagan administration, the attitude of Congress towards OSTP ranged from indifferenceto open hostility. Bromley, op. cit. , 39. Bush’s pre-election pledge to reestablish a body comparable to the President’s Science Advisory Committee,created by Eisenhower and abolished by Nixon, seems to have reflected Bromley’s views about the inadequacy of the WHSC. Bromley clearly enjoyed his membershipon the WHSC, but he believed that its membership was hampered in the formulation and implementation of a national science policy by its lack of direct access tothe president. During his first discussions with Bush about joining the new administration, Bromley insisted on three conditions, which the presidentaccepted:

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'A history of federal science policy from the new deal to the present' conversation and receive update notifications?