| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

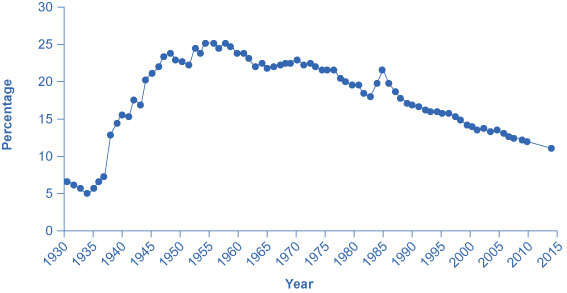

In terms of pay, benefits, and hiring, U.S. unions offer a good news/bad news story. The good news for unions and their members is that their members earn about 20% more than nonunion workers, even after adjusting for factors such as years of work experience and education level. The bad news for unions is that the share of U.S. workers who belong to a labor union has been steadily declining for 50 years, as shown in [link] . About one-quarter of all U.S. workers belonged to a union in the mid-1950s, but only 11.1% of U.S. workers are union members today. If you leave out workers employed by the government (which includes teachers in public schools), only 6.6% of the workers employed by private firms now work for a union.

The following section analyzes the higher pay union workers receive compared the pay rates for nonunion workers. The following section analyzes declining union membership levels. An overview of these two issues will allow us to discuss many aspects of how unions work.

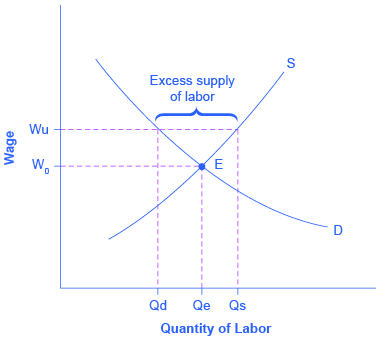

Why might union workers receive higher pay? What are the limits on how much higher pay they can receive? To analyze these questions, let’s consider a situation where all firms in an industry must negotiate with a single union, and no firm is allowed to hire nonunion labor. If no labor union existed in this market, then equilibrium (E) in the labor market would occur at the intersection of the demand for labor (D) and the supply of labor (S) in [link] . The union can, however, threaten that, unless firms agree to the wages they demand, the workers will strike. As a result, the labor union manages to achieve, through negotiations with the firms, a union wage of Wu for its members, above what the equilibrium wage would otherwise have been.

This labor market situation resembles what a monopoly firm does in selling a product, but in this case a union is a monopoly selling labor to firms. At the higher union wage Wu, the firms in this industry will hire less labor than they would have hired in equilibrium. Moreover, an excess supply of workers want union jobs, but firms will not be hiring for such jobs.

From the union point of view, workers who receive higher wages are better off. However, notice that the quantity of workers (Qd) hired at the union wage Wu is smaller than the quantity Qe that would have been hired at the original equilibrium wage. A sensible union must recognize that when it pushes up the wage, it also reduces the incentive of firms to hire. This situation does not necessarily mean that union workers are fired. Instead, it may be that when union workers move on to other jobs or retire, they are not always replaced. Or perhaps when a firm expands production, it expands employment somewhat less with a higher union wage than it would have done with the lower equilibrium wage. Or perhaps a firm decides to purchase inputs from nonunion producers, rather than producing them with its own highly paid unionized workers. Or perhaps the firm moves or opens a new facility in a state or country where unions are less powerful.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Microeconomics' conversation and receive update notifications?