| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

By the beginning of the 20th century, a great deal of work had already been done on characterizing DNA and establishing the foundations of genetics, including attributing heredity to chromosomes found within the nucleus. Despite all of this research, it was not until well into the 20th century that these lines of research converged and scientists began to consider that DNA could be the genetic material that offspring inherited from their parents. DNA, containing only four different nucleotides , was thought to be structurally too simple to encode such complex genetic information. Instead, protein was thought to have the complexity required to serve as cellular genetic information because it is composed of 20 different amino acids that could be combined in a huge variety of combinations. Microbiologists played a pivotal role in the research that determined that DNA is the molecule responsible for heredity .

British bacteriologist Frederick Griffith (1879–1941) was perhaps the first person to show that hereditary information could be transferred from one cell to another “horizontally” (between members of the same generation), rather than “vertically” (from parent to offspring). In 1928, he reported the first demonstration of bacterial transformation , a process in which external DNA is taken up by a cell, thereby changing its characteristics. F. Griffith. “The Significance of Pneumococcal Types.” Journal of Hygiene 27 no. 2 (1928):8–159. He was working with two strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae , a bacterium that causes pneumonia: a rough (R) strain and a smooth (S) strain. The R strain is nonpathogenic and lacks a capsule on its outer surface; as a result, colonies from the R strain appear rough when grown on plates. The S strain is pathogenic and has a capsule outside its cell wall, allowing it to escape phagocytosis by the host immune system. The capsules cause colonies from the S strain to appear smooth when grown on plates.

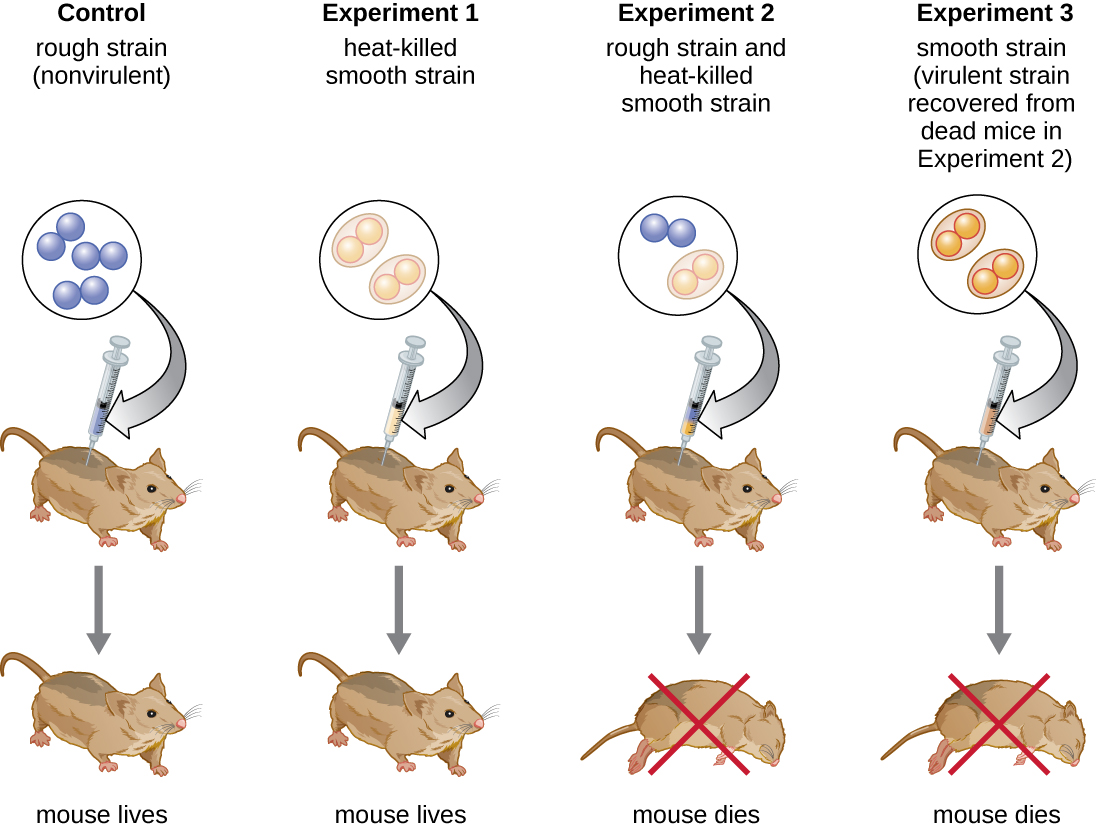

In a series of experiments, Griffith analyzed the effects of live R, live S, and heat-killed S strains of S. pneumoniae on live mice ( [link] ). When mice were injected with the live S strain, the mice died. When he injected the mice with the live R strain or the heat-killed S strain, the mice survived. But when he injected the mice with a mixture of live R strain and heat-killed S strain, the mice died. Upon isolating the live bacteria from the dead mouse, he only recovered the S strain of bacteria. When he then injected this isolated S strain into fresh mice, the mice died. Griffith concluded that something had passed from the heat-killed S strain into the live R strain and “transformed” it into the pathogenic S strain; he called this the “transforming principle.” These experiments are now famously known as Griffith’s transformation experiments .

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Microbiology' conversation and receive update notifications?