| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The organisms retrieved from arctic lakes such as Lake Whillans are considered extreme

psychrophile

s (cold loving). Psychrophiles are microorganisms that can grow at 0 °C and below, have an optimum growth temperature close to

15 °C, and usually do not survive at temperatures above 20 °C. They are found in permanently cold environments such as the deep waters of the oceans. Because they are active at low temperature, psychrophiles and psychrotrophs are important decomposers in cold climates.

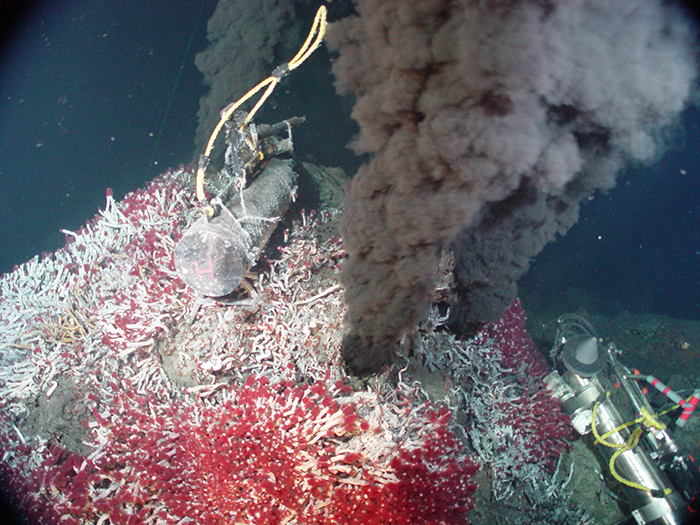

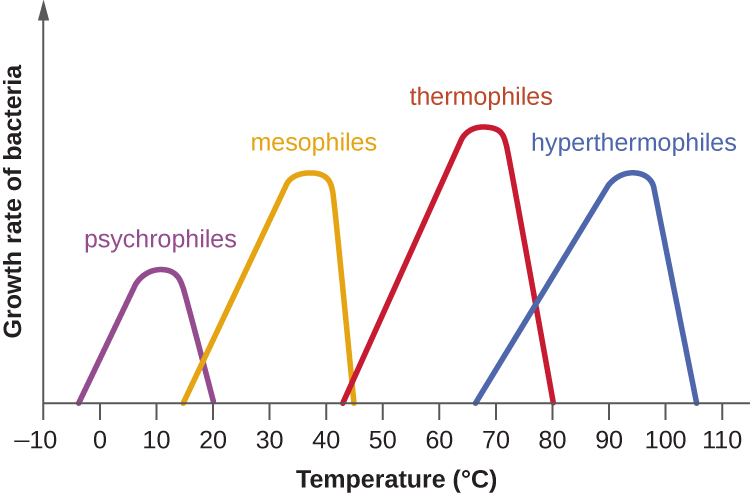

Organisms that grow at optimum temperatures of 50 °C to a maximum of 80 °C are called thermophiles (“heat loving”). They do not multiply at room temperature. Thermophiles are widely distributed in hot springs, geothermal soils, and manmade environments such as garden compost piles where the microbes break down kitchen scraps and vegetal material. Examples of thermophiles include Thermus aquaticus and Geobacillus spp. Higher up on the extreme temperature scale we find the hyperthermophiles , which are characterized by growth ranges from 80 °C to a maximum of 110 °C, with some extreme examples that survive temperatures above 121 °C, the average temperature of an autoclave. The hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the ocean are a prime example of extreme environments, with temperatures reaching an estimated 340 °C ( [link] ). Microbes isolated from the vents achieve optimal growth at temperatures higher than 100 °C. Noteworthy examples are Pyrobolus and Pyrodictium , archaea that grow at 105 °C and survive autoclaving. [link] shows the typical skewed curves of temperature-dependent growth for the categories of microorganisms we have discussed.

Life in extreme environments raises fascinating questions about the adaptation of macromolecules and metabolic processes. Very low temperatures affect cells in many ways. Membranes lose their fluidity and are damaged by ice crystal formation. Chemical reactions and diffusion slow considerably. Proteins become too rigid to catalyze reactions and may undergo denaturation. At the opposite end of the temperature spectrum, heat denatures proteins and nucleic acids. Increased fluidity impairs metabolic processes in membranes. Some of the practical applications of the destructive effects of heat on microbes are sterilization by steam, pasteurization, and incineration of inoculating loops. Proteins in psychrophiles are, in general, rich in hydrophobic residues, display an increase in flexibility, and have a lower number of secondary stabilizing bonds when compared with homologous proteins from mesophiles. Antifreeze proteins and solutes that decrease the freezing temperature of the cytoplasm are common. The lipids in the membranes tend to be unsaturated to increase fluidity. Growth rates are much slower than those encountered at moderate temperatures. Under appropriate conditions, mesophiles and even thermophiles can survive freezing. Liquid cultures of bacteria are mixed with sterile glycerol solutions and frozen to −80 °C for long-term storage as stocks. Cultures can withstand freeze drying (lyophilization) and then be stored as powders in sealed ampules to be reconstituted with broth when needed.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Microbiology' conversation and receive update notifications?