| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

While some scientists were arguing over the theory of spontaneous generation, other scientists were making discoveries leading to a better understanding of what we now call the cell theory . Modern cell theory has two basic tenets:

Today, these tenets are fundamental to our understanding of life on earth. However, modern cell theory grew out of the collective work of many scientists.

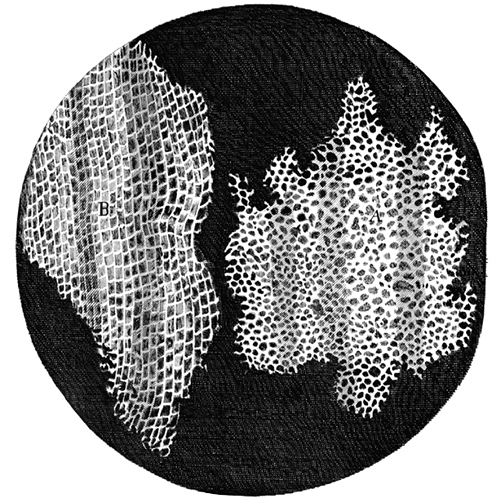

The English scientist Robert Hooke first used the term “cells” in 1665 to describe the small chambers within cork that he observed under a microscope of his own design. To Hooke, thin sections of cork resembled “Honey-comb,” or “small Boxes or Bladders of Air.” He noted that each “Cavern, Bubble, or Cell” was distinct from the others ( [link] ). At the time, Hooke was not aware that the cork cells were long dead and, therefore, lacked the internal structures found within living cells.

Despite Hooke’s early description of cells, their significance as the fundamental unit of life was not yet recognized. Nearly 200 years later, in 1838, Matthias Schleiden (1804–1881), a German botanist who made extensive microscopic observations of plant tissues, described them as being composed of cells. Visualizing plant cells was relatively easy because plant cells are clearly separated by their thick cell walls. Schleiden believed that cells formed through crystallization, rather than cell division.

Theodor Schwann (1810–1882), a noted German physiologist, made similar microscopic observations of animal tissue. In 1839, after a conversation with Schleiden, Schwann realized that similarities existed between plant and animal tissues. This laid the foundation for the idea that cells are the fundamental components of plants and animals.

In the 1850s, two Polish scientists living in Germany pushed this idea further, culminating in what we recognize today as the modern cell theory. In 1852, Robert Remak (1815–1865), a prominent neurologist and embryologist, published convincing evidence that cells are derived from other cells as a result of cell division. However, this idea was questioned by many in the scientific community. Three years later, Rudolf Virchow (1821–1902), a well-respected pathologist, published an editorial essay entitled “Cellular Pathology,” which popularized the concept of cell theory using the Latin phrase omnis cellula a cellula (“all cells arise from cells”), which is essentially the second tenet of modern cell theory. M. Schultz. “Rudolph Virchow.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 14 no. 9 (2008):1480–1481. Given the similarity of Virchow’s work to Remak’s, there is some controversy as to which scientist should receive credit for articulating cell theory. See the following Eye on Ethics feature for more about this controversy.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Microbiology' conversation and receive update notifications?