| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

For many STIs, it is common to contact and treat sexual partners of the patient. This is especially important when a new illness has appeared, as when HIV became more prevalent in the 1980s. But to contact sexual partners, it is necessary to obtain their personal information from the patient. This raises difficult questions. In some cases, providing the information may be embarrassing or difficult for the patient, even though withholding such information could put their sexual partner(s) at risk.

Legal considerations further complicate such situations. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA), passed into law in 1996, sets the standards for the protection of patient information. It requires businesses that use health information, such as insurance companies and healthcare providers, to maintain strict confidentiality of patient records. Contacting a patient’s sexual partners may therefore violate the patient’s privacy rights if the patient’s diagnosis is revealed as a result.

From an ethical standpoint, which is more important: the patient’s privacy rights or the sexual partner’s right to know that they may be at risk of a sexually transmitted disease? Does the answer depend on the severity of the disease or are the rules universal? Suppose the physician knows the identity of the sexual partner but the patient does not want that individual to be contacted. Would it be a violation of HIPPA rules to contact the individual without the patient’s consent?

Questions related to patient privacy become even more complicated when dealing with patients who are minors. Adolescents may be reluctant to discuss their sexual behavior or health with a health professional, especially if they believe that healthcare professionals will tell their parents. This leaves many teens at risk of having an untreated infection or of lacking the information to protect themselves and their partners. On the other hand, parents may feel that they have a right to know what is going on with their child. How should physicians handle this? Should parents always be told even if the adolescent wants confidentiality? Does this affect how the physician should handle notifying a sexual partner?

Vaginal candidiasis is generally treated using topical antifungal medications such as butoconazole, miconazole, clotrimazole, ticonozole, nystatin, or oral fluconazole. However, it is important to be careful in selecting a treatment for use during pregnancy. Nadia’s doctor recommended treatment with topical clotrimazole. This drug is classified as a category B drug by the FDA for use in pregnancy, and there appears to be no evidence of harm, at least in the second or third trimesters of pregnancy. Based on Nadia’s particular situation, her doctor thought that it was suitable for very short-term use even though she was still in the first trimester. After a seven-day course of treatment, Nadia’s yeast infection cleared. She continued with a normal pregnancy and delivered a healthy baby eight months later.

Higher levels of hormones during pregnancy can shift the typical microbiota composition and balance in the vagina, leading to high rates of infections such as candidiasis or vaginosis. Topical treatment has an 80–90% success rate, with only a small number of cases resulting in recurrent or persistent infections. Longer term or intermittent treatment is usually effective in these cases.

Go back to the previous Clinical Focus box.

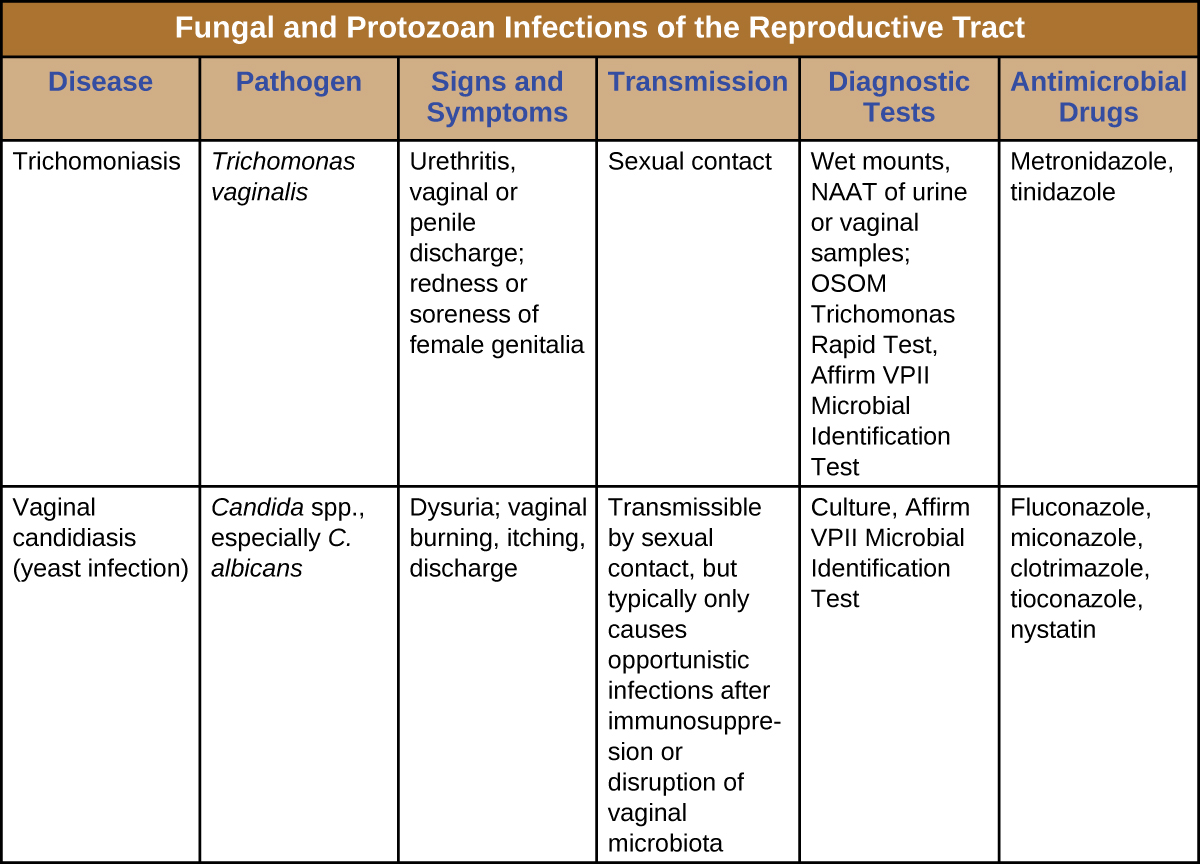

[link] summarizes the most important features of candidiasis and trichomoniasis.

Take an online quiz for a review of sexually transmitted infections.

Name three organisms (a bacterium, a fungus, and a protozoan) that are associated with vaginitis.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Microbiology' conversation and receive update notifications?