| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Some of the fundamental characteristics and functions of microscopes can be understood in the context of the history of their use. Italian scholar Girolamo Fracastoro is regarded as the first person to formally postulate that disease was spread by tiny invisible seminaria , or “seeds of the contagion.” In his book De Contagione (1546), he proposed that these seeds could attach themselves to certain objects (which he called fomes [cloth]) that supported their transfer from person to person. However, since the technology for seeing such tiny objects did not yet exist, the existence of the seminaria remained hypothetical for a little over a century—an invisible world waiting to be revealed.

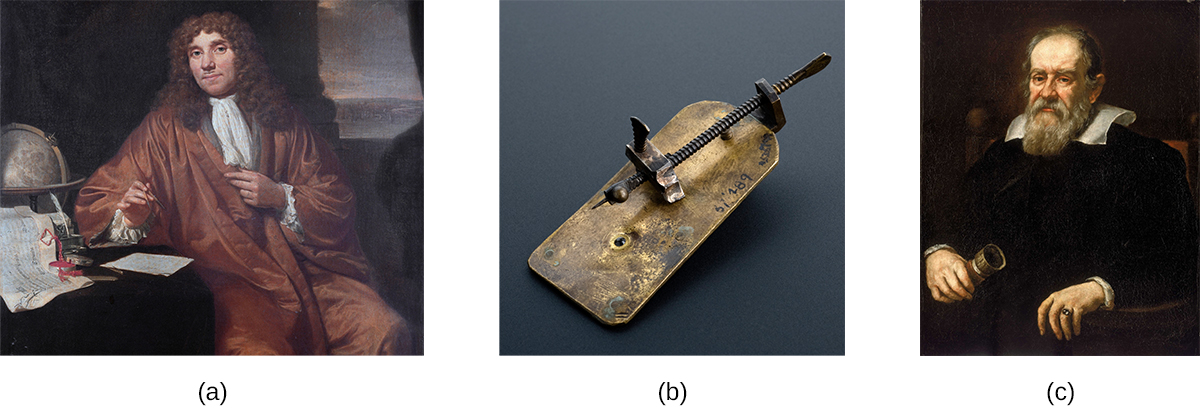

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek , sometimes hailed as “the Father of Microbiology,” is typically credited as the first person to have created microscopes powerful enough to view microbes ( [link] ). Born in the city of Delft in the Dutch Republic, van Leeuwenhoek began his career selling fabrics. However, he later became interested in lens making (perhaps to look at threads) and his innovative techniques produced microscopes that allowed him to observe microorganisms as no one had before. In 1674, he described his observations of single-celled organisms, whose existence was previously unknown, in a series of letters to the Royal Society of London. His report was initially met with skepticism, but his claims were soon verified and he became something of a celebrity in the scientific community.

While van Leeuwenhoek is credited with the discovery of microorganisms, others before him had contributed to the development of the microscope. These included eyeglass makers in the Netherlands in the late 1500s, as well as the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei, who used a compound microscope to examine insect parts ( [link] ). Whereas van Leeuwenhoek used a simple microscope , in which light is passed through just one lens, Galileo’s compound microscope was more sophisticated, passing light through two sets of lenses.

Van Leeuwenhoek’s contemporary, the Englishman Robert Hooke (1635–1703), also made important contributions to microscopy, publishing in his book Micrographia (1665) many observations using compound microscopes. Viewing a thin sample of cork through his microscope, he was the first to observe the structures that we now know as cells ( [link] ). Hooke described these structures as resembling “Honey-comb,” and as “small Boxes or Bladders of Air,” noting that each “Cavern, Bubble, or Cell” is distinct from the others (in Latin, “cell” literally means “small room”). They likely appeared to Hooke to be filled with air because the cork cells were dead, with only the rigid cell walls providing the structure.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Microbiology' conversation and receive update notifications?