| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

For most infectious diseases, the ability to accurately identify the causative pathogen is a critical step in finding or prescribing effective treatments. Today’s physicians, patients, and researchers owe a sizable debt to the physician Robert Koch (1843–1910), who devised a systematic approach for confirming causative relationships between diseases and specific pathogens.

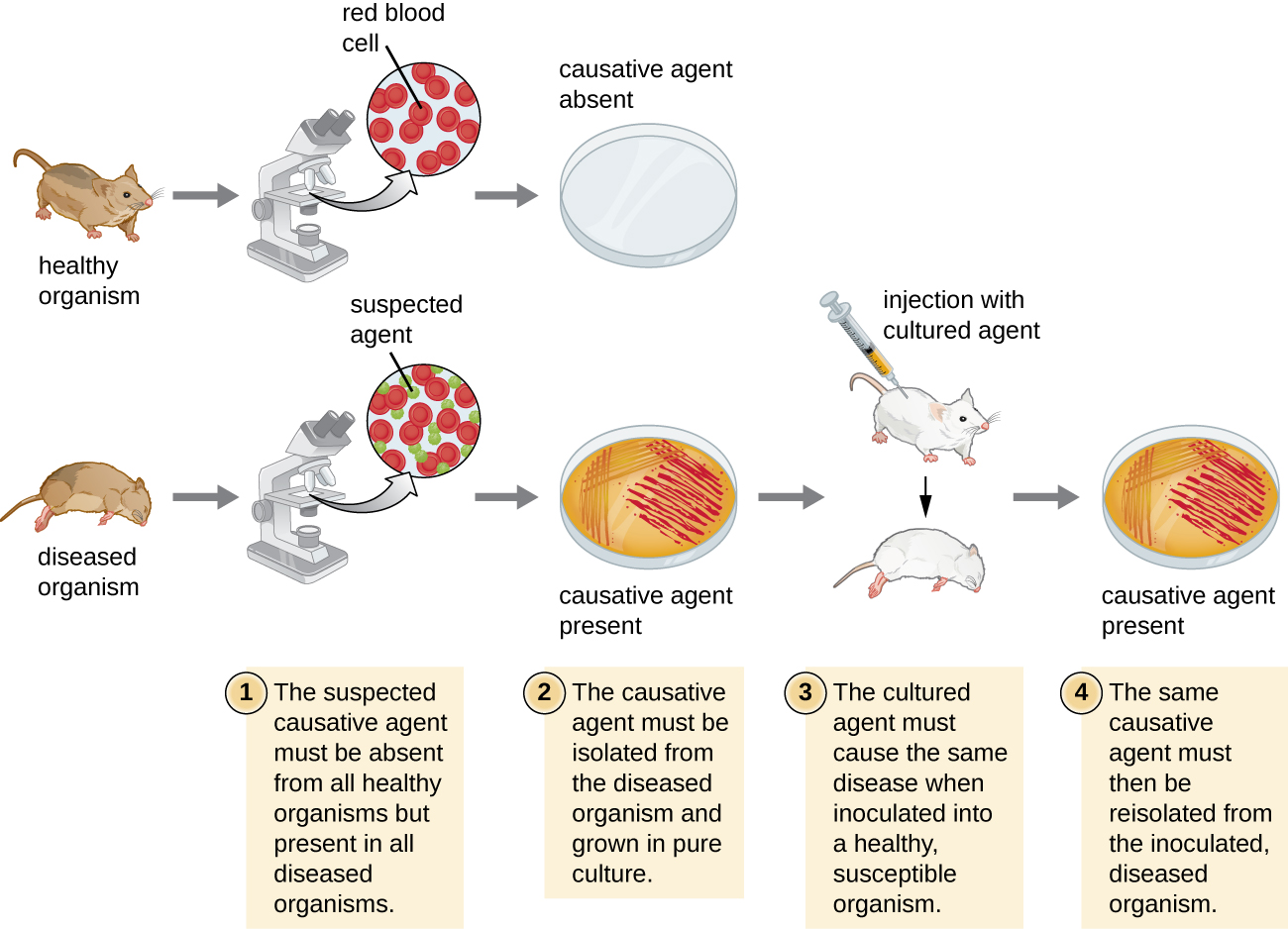

In 1884, Koch published four postulates ( [link] ) that summarized his method for determining whether a particular microorganism was the cause of a particular disease. Each of Koch’s postulates represents a criterion that must be met before a disease can be positively linked with a pathogen. In order to determine whether the criteria are met, tests are performed on laboratory animals and cultures from healthy and diseased animals are compared ( [link] ).

| Koch’s Postulates |

|---|

| (1) The suspected pathogen must be found in every case of disease and not be found in healthy individuals. |

| (2) The suspected pathogen can be isolated and grown in pure culture. |

| (3) A healthy test subject infected with the suspected pathogen must develop the same signs and symptoms of disease as seen in postulate 1. |

| (4) The pathogen must be re-isolated from the new host and must be identical to the pathogen from postulate 2. |

In many ways, Koch’s postulates are still central to our current understanding of the causes of disease. However, advances in microbiology have revealed some important limitations in Koch’s criteria. Koch made several assumptions that we now know are untrue in many cases. The first relates to postulate 1, which assumes that pathogens are only found in diseased, not healthy, individuals. This is not true for many pathogens. For example, H. pylori , described earlier in this chapter as a pathogen causing chronic gastritis, is also part of the normal microbiota of the stomach in many healthy humans who never develop gastritis. It is estimated that upwards of 50% of the human population acquires H. pylori early in life, with most maintaining it as part of the normal microbiota for the rest of their life without ever developing disease.

Koch’s second faulty assumption was that all healthy test subjects are equally susceptible to disease. We now know that individuals are not equally susceptible to disease. Individuals are unique in terms of their microbiota and the state of their immune system at any given time. The makeup of the resident microbiota can influence an individual’s susceptibility to an infection. Members of the normal microbiota play an important role in immunity by inhibiting the growth of transient pathogens. In some cases, the microbiota may prevent a pathogen from establishing an infection; in others, it may not prevent an infection altogether but may influence the severity or type of signs and symptoms. As a result, two individuals with the same disease may not always present with the same signs and symptoms. In addition, some individuals have stronger immune systems than others. Individuals with immune systems weakened by age or an unrelated illness are much more susceptible to certain infections than individuals with strong immune systems.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Microbiology' conversation and receive update notifications?