| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Antimicrobial resistance is not a new phenomenon. In nature, microbes are constantly evolving in order to overcome the antimicrobial compounds produced by other microorganisms. Human development of antimicrobial drugs and their widespread clinical use has simply provided another selective pressure that promotes further evolution. Several important factors can accelerate the evolution of drug resistance . These include the overuse and misuse of antimicrobials, inappropriate use of antimicrobials, subtherapeutic dosing, and patient noncompliance with the recommended course of treatment.

Exposure of a pathogen to an antimicrobial compound can select for chromosomal mutations conferring resistance, which can be transferred vertically to subsequent microbial generations and eventually become predominant in a microbial population that is repeatedly exposed to the antimicrobial. Alternatively, many genes responsible for drug resistance are found on plasmids or in transposons that can be transferred easily between microbes through horizontal gene transfer (see How Asexual Prokaryotes Achieve Genetic Diversity ). Transposons also have the ability to move resistance genes between plasmids and chromosomes to further promote the spread of resistance.

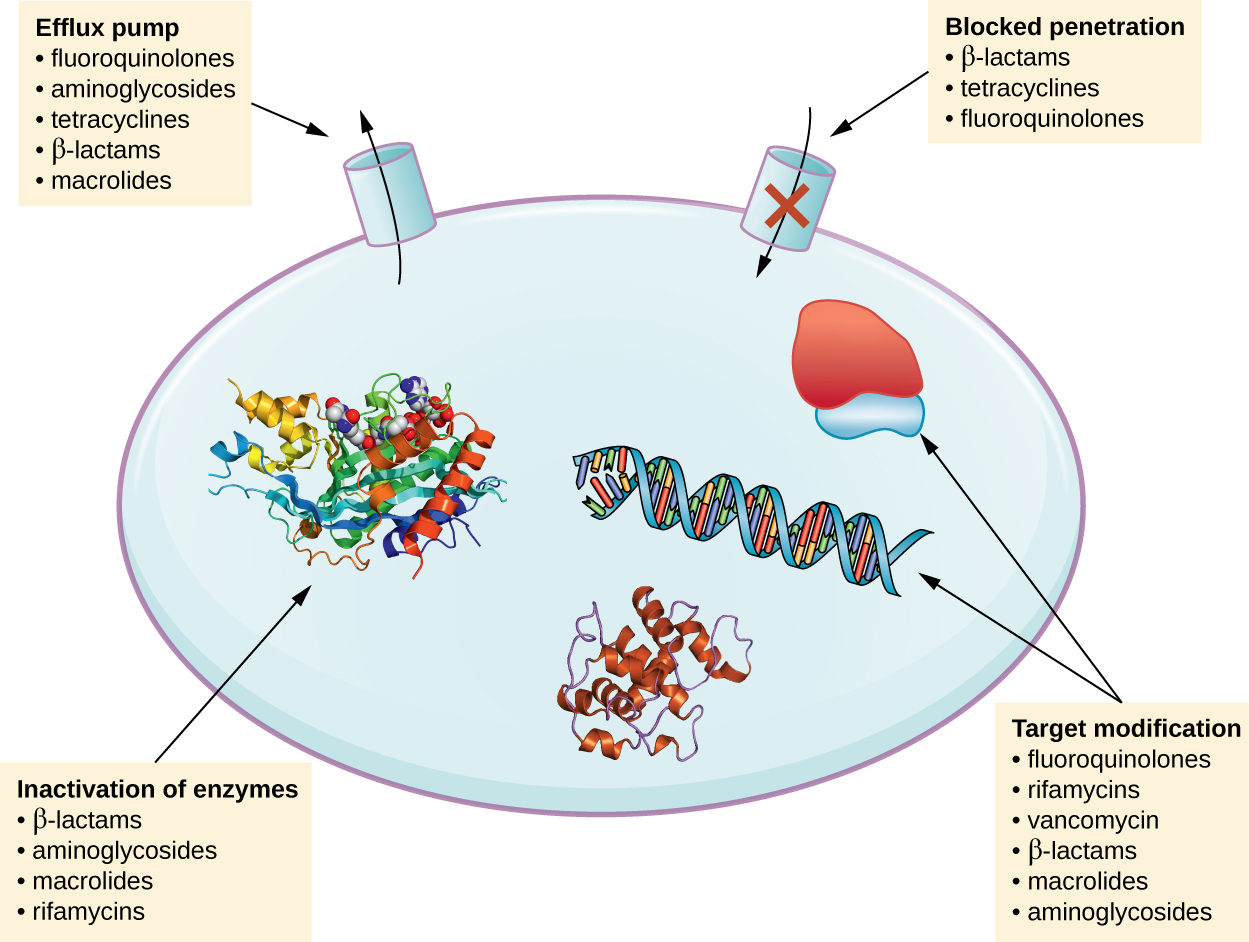

There are several common mechanisms for drug resistance, which are summarized in [link] . These mechanisms include enzymatic modification of the drug, modification of the antimicrobial target, and prevention of drug penetration or accumulation.

Resistance genes may code for enzymes that chemically modify an antimicrobial, thereby inactivating it, or destroy an antimicrobial through hydrolysis. Resistance to many types of antimicrobials occurs through this mechanism. For example, aminoglycoside resistance can occur through enzymatic transfer of chemical groups to the drug molecule, impairing the binding of the drug to its bacterial target. For β-lactams , bacterial resistance can involve the enzymatic hydrolysis of the β-lactam bond within the β-lactam ring of the drug molecule. Once the β-lactam bond is broken, the drug loses its antibacterial activity. This mechanism of resistance is mediated by β-lactamases , which are the most common mechanism of β-lactam resistance. Inactivation of rifampin commonly occurs through glycosylation , phosphorylation , or adenosine diphosphate (ADP) ribosylation, and resistance to macrolides and lincosamides can also occur due to enzymatic inactivation of the drug or modification.

Microbes may develop resistance mechanisms that involve inhibiting the accumulation of an antimicrobial drug, which then prevents the drug from reaching its cellular target. This strategy is common among gram-negative pathogens and can involve changes in outer membrane lipid composition, porin channel selectivity, and/or porin channel concentrations. For example, a common mechanism of carbapenem resistance among Pseudomonas aeruginosa is to decrease the amount of its OprD porin, which is the primary portal of entry for carbapenems through the outer membrane of this pathogen. Additionally, many gram-positive and gram-negative pathogenic bacteria produce efflux pump s that actively transport an antimicrobial drug out of the cell and prevent the accumulation of drug to a level that would be antibacterial. For example, resistance to β-lactams, tetracyclines , and fluoroquinolones commonly occurs through active efflux out of the cell, and it is rather common for a single efflux pump to have the ability to translocate multiple types of antimicrobials.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Microbiology' conversation and receive update notifications?