| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

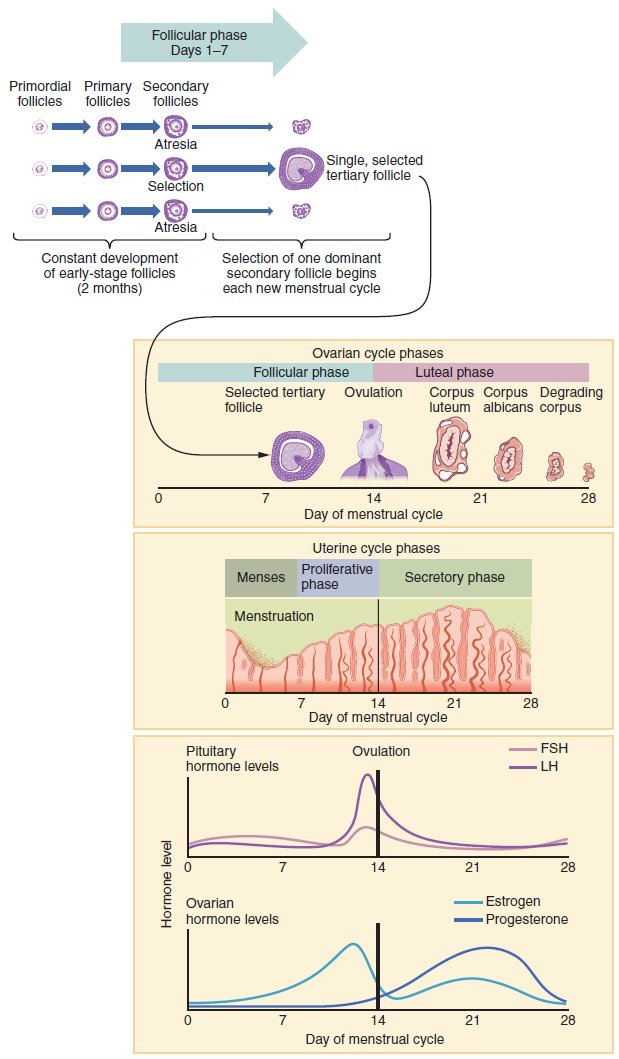

Once menstrual flow ceases, the endometrium begins to proliferate again, marking the beginning of the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle (see [link] ). It occurs when the granulosa and theca cells of the tertiary follicles begin to produce increased amounts of estrogen. These rising estrogen concentrations stimulate the endometrial lining to rebuild.

Recall that the high estrogen concentrations will eventually lead to a decrease in FSH as a result of negative feedback, resulting in atresia of all but one of the developing tertiary follicles. The switch to positive feedback—which occurs with the elevated estrogen production from the dominant follicle—then stimulates the LH surge that will trigger ovulation. In a typical 28-day menstrual cycle, ovulation occurs on day 14. Ovulation marks the end of the proliferative phase as well as the end of the follicular phase.

In addition to prompting the LH surge, high estrogen levels increase the uterine tube contractions that facilitate the pick-up and transfer of the ovulated oocyte. High estrogen levels also slightly decrease the acidity of the vagina, making it more hospitable to sperm. In the ovary, the luteinization of the granulosa cells of the collapsed follicle forms the progesterone-producing corpus luteum, marking the beginning of the luteal phase of the ovarian cycle. In the uterus, progesterone from the corpus luteum begins the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle, in which the endometrial lining prepares for implantation (see [link] ). Over the next 10 to 12 days, the endometrial glands secrete a fluid rich in glycogen. If fertilization has occurred, this fluid will nourish the ball of cells now developing from the zygote. At the same time, the spiral arteries develop to provide blood to the thickened stratum functionalis.

If no pregnancy occurs within approximately 10 to 12 days, the corpus luteum will degrade into the corpus albicans. Levels of both estrogen and progesterone will fall, and the endometrium will grow thinner. Prostaglandins will be secreted that cause constriction of the spiral arteries, reducing oxygen supply. The endometrial tissue will die, resulting in menses—or the first day of the next cycle.

HPV infections are common in both men and women. Indeed, a recent study determined that 42.5 percent of females had HPV at the time of testing. These women ranged in age from 14 to 59 years and differed in race, ethnicity, and number of sexual partners. Of note, the prevalence of HPV infection was 53.8 percent among women aged 20 to 24 years, the age group with the highest infection rate.

HPV strains are classified as high or low risk according to their potential to cause cancer. Though most HPV infections do not cause disease, the disruption of normal cellular functions in the low-risk forms of HPV can cause the male or female human host to develop genital warts. Often, the body is able to clear an HPV infection by normal immune responses within 2 years. However, the more serious, high-risk infection by certain types of HPV can result in cancer of the cervix ( [link] ). Infection with either of the cancer-causing variants HPV 16 or HPV 18 has been linked to more than 70 percent of all cervical cancer diagnoses. Although even these high-risk HPV strains can be cleared from the body over time, infections persist in some individuals. If this happens, the HPV infection can influence the cells of the cervix to develop precancerous changes.

Risk factors for cervical cancer include having unprotected sex; having multiple sexual partners; a first sexual experience at a younger age, when the cells of the cervix are not fully mature; failure to receive the HPV vaccine; a compromised immune system; and smoking. The risk of developing cervical cancer is doubled with cigarette smoking.

When the high-risk types of HPV enter a cell, two viral proteins are used to neutralize proteins that the host cells use as checkpoints in the cell cycle. The best studied of these proteins is p53. In a normal cell, p53 detects DNA damage in the cell’s genome and either halts the progression of the cell cycle—allowing time for DNA repair to occur—or initiates apoptosis. Both of these processes prevent the accumulation of mutations in a cell’s genome. High-risk HPV can neutralize p53, keeping the cell in a state in which fast growth is possible and impairing apoptosis, allowing mutations to accumulate in the cellular DNA.

The prevalence of cervical cancer in the United States is very low because of regular screening exams called pap smears. Pap smears sample cells of the cervix, allowing the detection of abnormal cells. If pre-cancerous cells are detected, there are several highly effective techniques that are currently in use to remove them before they pose a danger. However, women in developing countries often do not have access to regular pap smears. As a result, these women account for as many as 80 percent of the cases of cervical cancer worldwide.

In 2006, the first vaccine against the high-risk types of HPV was approved. There are now two HPV vaccines available: Gardasil ® and Cervarix ® . Whereas these vaccines were initially only targeted for women, because HPV is sexually transmitted, both men and women require vaccination for this approach to achieve its maximum efficacy. A recent study suggests that the HPV vaccine has cut the rates of HPV infection by the four targeted strains at least in half. Unfortunately, the high cost of manufacturing the vaccine is currently limiting access to many women worldwide.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Anatomy & Physiology' conversation and receive update notifications?