| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

As discussed earlier, the shape of a protein is critical to its function. For example, an enzyme can bind to a specific substrate at a site known as the active site. If this active site is altered because of local changes or changes in overall protein structure, the enzyme may be unable to bind to the substrate. To understand how the protein gets its final shape or conformation, we need to understand the four levels of protein structure: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary. For a short (4 minutes) introduction video on protein structure click here .

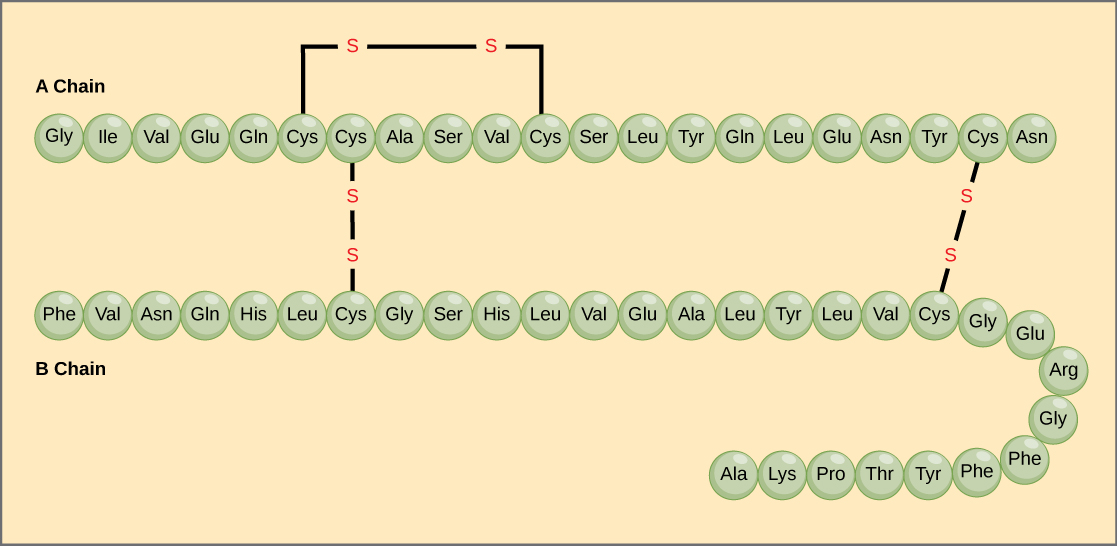

The unique sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain is its primary structure . For example, the pancreatic hormone insulin has two polypeptide chains, A and B, and they are linked together by disulfide bonds. The N terminal amino acid of the A chain is glycine, whereas the C terminal amino acid is asparagine ( [link] ). The sequences of amino acids in the A and B chains are unique to insulin.

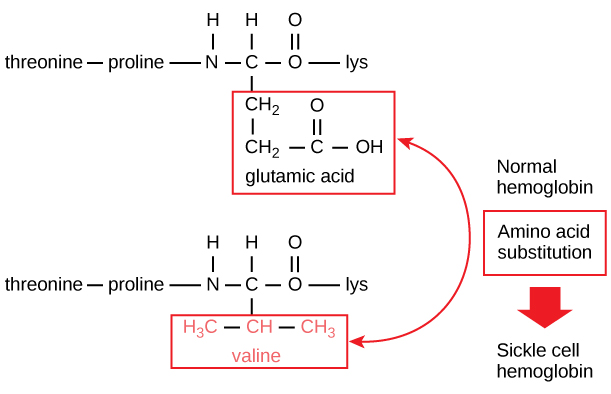

The unique sequence for every protein is ultimately determined by the gene encoding the protein. A change in nucleotide sequence of the gene’s coding region may lead to a different amino acid being added to the growing polypeptide chain, causing a change in protein structure and function. In sickle cell anemia, the hemoglobin β chain (a small portion of which is shown in [link] ) has a single amino acid substitution, causing a change in protein structure and function. Specifically, the amino acid glutamic acid is substituted by valine in the β chain. What is most remarkable to consider is that a hemoglobin molecule is made up of two alpha chains and two beta chains that each consist of about 150 amino acids. The molecule, therefore, has about 600 amino acids. The structural difference between a normal hemoglobin molecule and a sickle cell molecule—which dramatically decreases life expectancy—is a single amino acid of the 600. What is even more remarkable is that those 600 amino acids are encoded by three nucleotides each, and the mutation is caused by a single base change (point mutation), 1 in 1800 bases.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Cellular macromolecules: bis2a modules 3.0 to 3.5' conversation and receive update notifications?