| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The hornworts ( Anthocerotophyta ) belong to the broad bryophyte group. They have colonized a variety of habitats on land, although they are never far from a source of moisture. The short, blue-green gametophyte is the dominant phase of the lifecycle of a hornwort. The narrow, pipe-like sporophyte is the defining characteristic of the group. The sporophytes emerge from the parent gametophyte and continue to grow throughout the life of the plant ( [link] ).

Stomata appear in the hornworts and are abundant on the sporophyte. Photosynthetic cells in the thallus contain a single chloroplast. Meristem cells at the base of the plant keep dividing and adding to its height. Many hornworts establish symbiotic relationships with cyanobacteria that fix nitrogen from the environment.

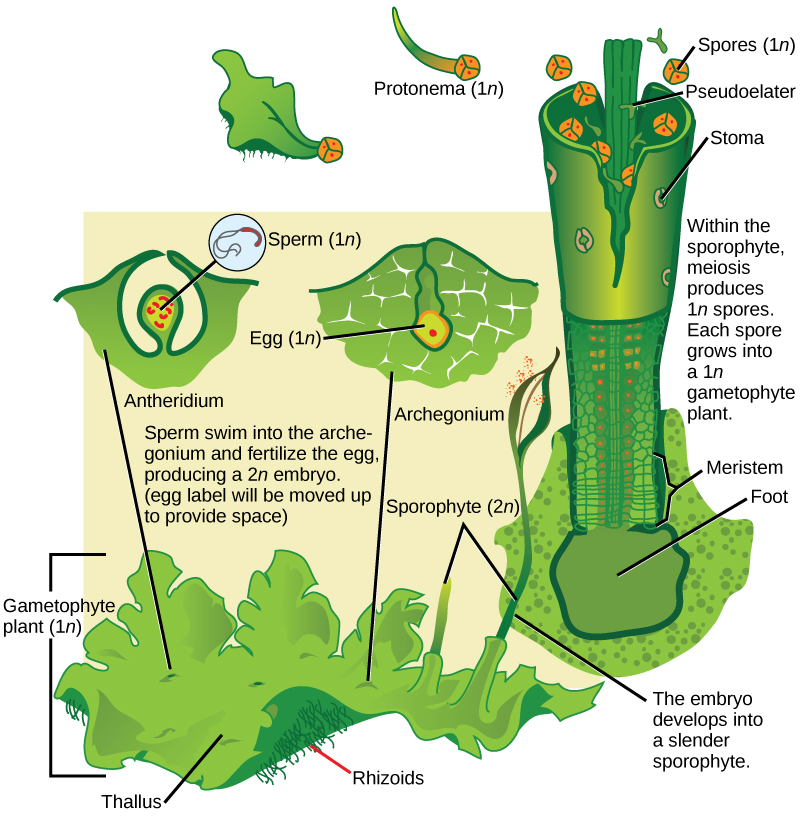

The lifecycle of hornworts ( [link] ) follows the general pattern of alternation of generations. The gametophytes grow as flat thalli on the soil with embedded gametangia. Flagellated sperm swim to the archegonia and fertilize eggs. The zygote develops into a long and slender sporophyte that eventually splits open, releasing spores. Thin cells called pseudoelaters surround the spores and help propel them further in the environment. Unlike the elaters observed in horsetails, the hornwort pseudoelaters are single-celled structures. The haploid spores germinate and give rise to the next generation of gametophyte.

More than 10,000 species of mosses have been catalogued. Their habitats vary from the tundra, where they are the main vegetation, to the understory of tropical forests. In the tundra, the mosses’ shallow rhizoids allow them to fasten to a substrate without penetrating the frozen soil. Mosses slow down erosion, store moisture and soil nutrients, and provide shelter for small animals as well as food for larger herbivores, such as the musk ox. Mosses are very sensitive to air pollution and are used to monitor air quality. They are also sensitive to copper salts, so these salts are a common ingredient of compounds marketed to eliminate mosses from lawns.

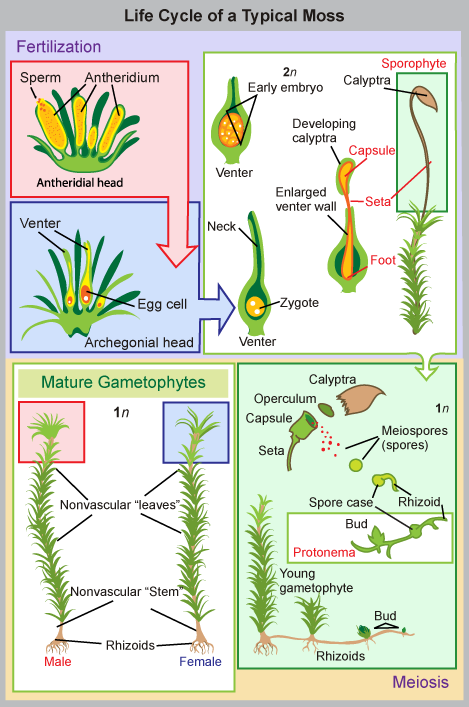

Mosses form diminutive gametophytes, which are the dominant phase of the lifecycle. Green, flat structures—resembling true leaves, but lacking vascular tissue—are attached in a spiral to a central stalk. The plants absorb water and nutrients directly through these leaf-like structures. Some mosses have small branches. Some primitive traits of green algae, such as flagellated sperm, are still present in mosses that are dependent on water for reproduction. Other features of mosses are clearly adaptations to dry land. For example, stomata are present on the stems of the sporophyte, and a primitive vascular system runs up the sporophyte’s stalk. Additionally, mosses are anchored to the substrate—whether it is soil, rock, or roof tiles—by multicellular rhizoids . These structures are precursors of roots. They originate from the base of the gametophyte, but are not the major route for the absorption of water and minerals. The lack of a true root system explains why it is so easy to rip moss mats from a tree trunk. The moss lifecycle follows the pattern of alternation of generations as shown in [link] . The most familiar structure is the haploid gametophyte, which germinates from a haploid spore and forms first a protonema —usually, a tangle of single-celled filaments that hug the ground. Cells akin to an apical meristem actively divide and give rise to a gametophore, consisting of a photosynthetic stem and foliage-like structures. Rhizoids form at the base of the gametophore. Gametangia of both sexes develop on separate gametophores. The male organ (the antheridium) produces many sperm, whereas the archegonium (the female organ) forms a single egg. At fertilization, the sperm swims down the neck to the venter and unites with the egg inside the archegonium. The zygote, protected by the archegonium, divides and grows into a sporophyte, still attached by its foot to the gametophyte.

Which of the following statements about the moss life cycle is false?

The slender seta (plural, setae), as seen in [link] , contains tubular cells that transfer nutrients from the base of the sporophyte (the foot) to the sporangium or capsule .

A structure called a peristome increases the spread of spores after the tip of the capsule falls off at dispersal. The concentric tissue around the mouth of the capsule is made of triangular, close-fitting units, a little like “teeth”; these open and close depending on moisture levels, and periodically release spores.

Seedless nonvascular plants are small, having the gametophyte as the dominant stage of the lifecycle. Without a vascular system and roots, they absorb water and nutrients on all their exposed surfaces. Collectively known as bryophytes, the three main groups include the liverworts, the hornworts, and the mosses. Liverworts are the most primitive plants and are closely related to the first land plants. Hornworts developed stomata and possess a single chloroplast per cell. Mosses have simple conductive cells and are attached to the substrate by rhizoids. They colonize harsh habitats and can regain moisture after drying out. The moss sporangium is a complex structure that allows release of spores away from the parent plant.

[link] Which of the following statements about the moss life cycle is false?

[link] C.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Biology' conversation and receive update notifications?