| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

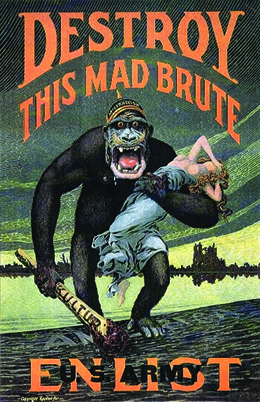

The Wilson administration created the Committee of Public Information under director George Creel, a former journalist, just days after the United States declared war on Germany. Creel employed artists, speakers, writers, and filmmakers to develop a propaganda machine. The goal was to encourage all Americans to make sacrifices during the war and, equally importantly, to hate all things German ( [link] ). Through efforts such as the establishment of “loyalty leagues” in ethnic immigrant communities, Creel largely succeeded in molding an anti-German sentiment around the country. The result? Some schools banned the teaching of the German language and some restaurants refused to serve frankfurters, sauerkraut, or hamburgers, instead serving “liberty dogs with liberty cabbage” and “liberty sandwiches.” Symphonies refused to perform music written by German composers. The hatred of Germans grew so widespread that, at one point, at a circus, audience members cheered when, in an act gone horribly wrong, a Russian bear mauled a German animal trainer (whose ethnicity was more a part of the act than reality).

In addition to its propaganda campaign, the U.S. government also tried to secure broad support for the war effort with repressive legislation. The Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917 prohibited individual trade with an enemy nation and banned the use of the postal service for disseminating any literature deemed treasonous by the postmaster general. That same year, the Espionage Act prohibited giving aid to the enemy by spying, or espionage, as well as any public comments that opposed the American war effort. Under this act, the government could impose fines and imprisonment of up to twenty years. The Sedition Act, passed in 1918, prohibited any criticism or disloyal language against the federal government and its policies, the U.S. Constitution, the military uniform, or the American flag. More than two thousand persons were charged with violating these laws, and many received prison sentences of up to twenty years. Immigrants faced deportation as punishment for their dissent. Not since the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 had the federal government so infringed on the freedom of speech of loyal American citizens.

For a sense of the response and pushback that antiwar sentiments incited, read this newspaper article from 1917, discussing the dissemination of 100,000 antidraft flyers by the No Conscription League.

In the months and years after these laws came into being, over one thousand people were convicted for their violation, primarily under the Espionage and Sedition Acts. More importantly, many more war critics were frightened into silence. One notable prosecution was that of Socialist Party leader Eugene Debs, who received a ten-year prison sentence for encouraging draft resistance, which, under the Espionage Act, was considered “giving aid to the enemy.” Prominent Socialist Victor Berger was also prosecuted under the Espionage Act and subsequently twice denied his seat in Congress, to which he had been properly elected by the citizens of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. One of the more outrageous prosecutions was that of a film producer who released a film about the American Revolution: Prosecutors found the film seditious, and a court convicted the producer to ten years in prison for portraying the British, who were now American allies, as the obedient soldiers of a monarchical empire.

State and local officials, as well as private citizens, aided the government’s efforts to investigate, identify, and crush subversion. Over 180,000 communities created local “councils of defense,” which encouraged members to report any antiwar comments to local authorities. This mandate encouraged spying on neighbors, teachers, local newspapers, and other individuals. In addition, a larger national organization—the American Protective League—received support from the Department of Justice to spy on prominent dissenters, as well as open their mail and physically assault draft evaders.

Understandably, opposition to such repression began mounting. In 1917, Roger Baldwin formed the National Civil Liberties Bureau—a forerunner to the American Civil Liberties Union, which was founded in 1920—to challenge the government’s policies against wartime dissent and conscientious objection. In 1919, the case of Schenck v. United States went to the U.S. Supreme Court to challenge the constitutionality of the Espionage and Sedition Acts. The case concerned Charles Schenck, a leader in the Socialist Party of Philadelphia, who had distributed fifteen thousand leaflets, encouraging young men to avoid conscription. The court ruled that during a time of war, the federal government was justified in passing such laws to quiet dissenters. The decision was unanimous, and in the court’s opinion, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote that such dissent presented a “ clear and present danger ” to the safety of the United States and the military, and was therefore justified. He further explained how the First Amendment right of free speech did not protect such dissent, in the same manner that a citizen could not be freely permitted to yell “fire!” in a crowded theater, due to the danger it presented. Congress ultimately repealed most of the Espionage and Sedition Acts in 1921, and several who were imprisoned for violation of those acts were then quickly released. But the Supreme Court’s deference to the federal government’s restrictions on civil liberties remained a volatile topic in future wars.

Wilson might have entered the war unwillingly, but once it became inevitable, he quickly moved to use federal legislation and government oversight to put into place the conditions for the nation’s success. First, he sought to ensure that all logistical needs—from fighting men to raw materials for wartime production—were in place and within government reach. From legislating rail service to encouraging Americans to buy liberty loans and “bring the boys home sooner,” the government worked to make sure that the conditions for success were in place. Then came the more nuanced challenge of ensuring that a country of immigrants from both sides of the conflict fell in line as Americans, first and foremost. Aggressive propaganda campaigns, combined with a series of restrictive laws to silence dissenters, ensured that Americans would either support the war or at least stay silent. While some conscientious objectors and others spoke out, the government efforts were largely successful in silencing those who had favored neutrality.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?