| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

While many now assume the United States was founded as a democracy, history, as always, is more complicated. Conservative Whigs believed in government by a patrician class, a ruling group composed of a small number of privileged families. Radical Whigs favored broadening the popular participation in political life and pushed for democracy. The great debate after independence was secured centered on this question: Who should rule in the new American republic?

According to political theory, a republic requires its citizens to cultivate virtuous behavior; if the people are virtuous, the republic will survive. If the people become corrupt, the republic will fall. Whether republicanism succeeded or failed in the United States would depend on civic virtue and an educated citizenry. Revolutionary leaders agreed that the ownership of property provided one way to measure an individual’s virtue, arguing that property holders had the greatest stake in society and therefore could be trusted to make decisions for it. By the same token, non-property holders, they believed, should have very little to do with government. In other words, unlike a democracy, in which the mass of non-property holders could exercise the political right to vote, a republic would limit political rights to property holders. In this way, republicanism exhibited a bias toward the elite, a preference that is understandable given the colonial legacy. During colonial times, wealthy planters and merchants in the American colonies had looked to the British ruling class, whose social order demanded deference from those of lower rank, as a model of behavior. Old habits died hard.

In the 1780s, Benjamin Franklin carefully defined thirteen virtues to help guide his countrymen in maintaining a virtuous republic. His choice of thirteen is telling since he wrote for the citizens of the thirteen new American republics. These virtues were:

1. Temperance. Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation.

2. Silence. Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation.

3. Order. Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time.

4. Resolution. Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve.

5. Frugality. Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e., waste nothing.

6. Industry. Lose no time; be always employ’d in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions.

7. Sincerity. Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly, and, if you speak, speak accordingly.

8. Justice. Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty.

9. Moderation. Avoid extremes; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve.

10. Cleanliness. Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, cloaths, or habitation.

11. Tranquillity. Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable.

12. Chastity. Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dullness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another’s peace or reputation.

13. Humility. Imitate Jesus and Socrates.

Franklin’s thirteen virtues suggest that hard work and good behavior will bring success. What factors does Franklin ignore? How would he likely address a situation in which children inherit great wealth rather than working for it? How do Franklin’s values help to define the notion of republican virtue?

Check how well you are demonstrating all thirteen of Franklin’s virtues on thirteenvirtues.com, where you can register to track your progress.

George Washington served as a role model par excellence for the new republic, embodying the exceptional talent and public virtue prized under the political and social philosophy of republicanism. He did not seek to become the new king of America; instead he retired as commander in chief of the Continental Army and returned to his Virginia estate at Mount Vernon to resume his life among the planter elite. Washington modeled his behavior on that of the Roman aristocrat Cincinnatus, a representative of the patrician or ruling class, who had also retired from public service in the Roman Republic and returned to his estate to pursue agricultural life.

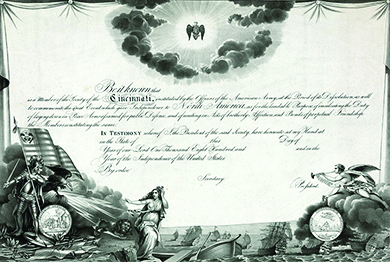

The aristocratic side of republicanism—and the belief that the true custodians of public virtue were those who had served in the military—found expression in the Society of the Cincinnati, of which Washington was the first president general ( [link] ). Founded in 1783, the society admitted only officers of the Continental Army and the French forces, not militia members or minutemen. Following the rule of primogeniture, the eldest sons of members inherited their fathers’ memberships. The society still exists today and retains the motto Omnia relinquit servare rempublicam (“He relinquished everything to save the Republic”).

The guiding principle of republicanism was that the people themselves would appoint or select the leaders who would represent them. The debate over how much democracy (majority rule) to incorporate in the governing of the new United States raised questions about who was best qualified to participate in government and have the right to vote. Revolutionary leaders argued that property holders had the greatest stake in society and favored a republic that would limit political rights to property holders. In this way, republicanism exhibited a bias toward the elite. George Washington served as a role model for the new republic, embodying the exceptional talent and public virtue prized in its political and social philosophy.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?