| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The new Negro found political expression in a political ideology that celebrated African Americans distinct national identity. This Negro nationalism , as some referred to it, proposed that African Americans had a distinct and separate national heritage that should inspire pride and a sense of community. An early proponent of such nationalism was W. E. B. Du Bois. One of the founders of the NAACP, a brilliant writer and scholar, and the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard, Du Bois openly rejected assumptions of white supremacy. His conception of Negro nationalism encouraged Africans to work together in support of their own interests, promoted the elevation of black literature and cultural expression, and, most famously, embraced the African continent as the true homeland of all ethnic Africans—a concept known as Pan-Africanism.

Taking Negro nationalism to a new level was Marcus Garvey. Like many black Americans, the Jamaican immigrant had become utterly disillusioned with the prospect of overcoming white racism in the United States in the wake of the postwar riots and promoted a “Back to Africa” movement. To return African Americans to a presumably more welcoming home in Africa, Garvey founded the Black Star Steamship Line . He also started the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), which attracted thousands of primarily lower-income working people. UNIA members wore colorful uniforms and promoted the doctrine of a “negritude” that reversed the color hierarchy of white supremacy, prizing blackness and identifying light skin as a mark of inferiority. Intellectual leaders like Du Bois, whose lighter skin put him low on Garvey’s social order, considered the UNIA leader a charlatan. Garvey was eventually imprisoned for mail fraud and then deported, but his legacy set the stage for Malcolm X and the Black Power movement of the 1960s.

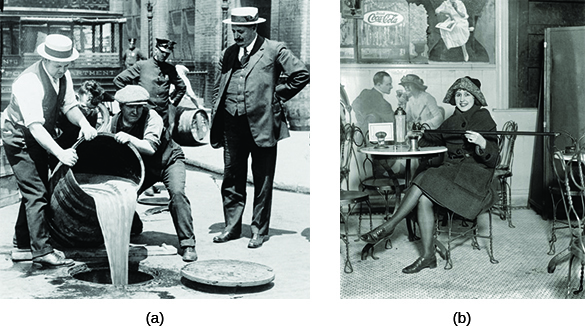

At precisely the same time that African Americans and women were experimenting with new forms of social expression, the country as a whole was undergoing a process of austere and dramatic social reform in the form of alcohol prohibition. After decades of organizing to reduce or end the consumption of alcohol in the United States, temperance groups and the Anti-Saloon League finally succeeded in pushing through the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919, which banned the manufacture, sale, and transportation of intoxicating liquors ( [link] ). The law proved difficult to enforce, as illegal alcohol soon poured in from Canada and the Caribbean, and rural Americans resorted to home-brewed “moonshine.” The result was an eroding of respect for law and order, as many people continued to drink illegal liquor. Rather than bringing about an age of sobriety, as Progressive reformers had hoped, it gave rise to a new subculture that included illegal importers, interstate smuggling (or bootlegging ), clandestine saloons referred to as “speakeasies,” hipflasks, cocktail parties, and the organized crime of trafficking liquor.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?