| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

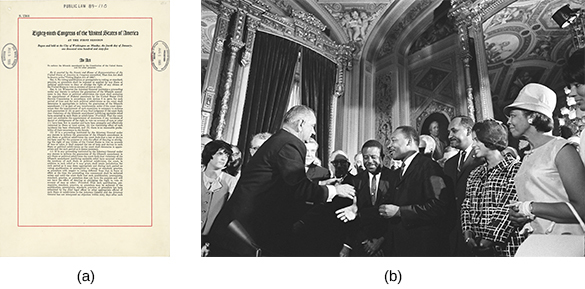

Building the Great Society had been Lyndon Johnson’s biggest priority, and he effectively used his decades of experience in building legislative majorities in a style that ranged from diplomacy to quid pro quo deals to bullying. In the summer of 1964, he deployed these political skills to secure congressional approval for a new strategy in Vietnam—with fateful consequences.

President Johnson had never been the cold warrior Kennedy was, but believed that the credibility of the nation and his office depended on maintaining a foreign policy of containment. When, on August 2, the U.S. destroyer USS Maddox conducted an arguably provocative intelligence-gathering mission in the gulf of Tonkin, it reported an attack by North Vietnamese torpedo boats. Two days later, the Maddox was supposedly struck again, and a second ship, the USS Turner Joy , reported that it also had been fired upon. The North Vietnamese denied the second attack, and Johnson himself doubted the reliability of the crews’ report. The National Security Agency has since revealed that the August 4 attacks did not occur. Relying on information available at the time, however, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara reported to Congress that U.S. ships had been fired upon in international waters while conducting routine operations. On August 7, with only two dissenting votes, Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, and on August 10, the president signed the resolution into law. The resolution gave President Johnson the authority to use military force in Vietnam without asking Congress for a declaration of war. It dramatically increased the power of the U.S. president and transformed the American role in Vietnam from advisor to combatant.

In 1965, large-scale U.S. bombing of North Vietnam began. The intent of the campaign, which lasted three years under various names, was to force the North to end its support for the insurgency in the South. More than 200,000 U.S. military personnel, including combat troops, were sent to South Vietnam. At first, most of the American public supported the president’s actions in Vietnam. Support began to ebb, however, as more troops were deployed. Frustrated by losses suffered by the South’s Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), General William Westmoreland called for the United States to take more responsibility for fighting the war. By April 1966, more Americans were being killed in battle than ARVN troops. Johnson, however, maintained that the war could be won if the United States stayed the course, and in November 1967, Westmoreland proclaimed the end was in sight.

To hear one soldier’s story about his time in Vietnam, listen to Sergeant Charles G. Richardson’s recollections of his experience on the ground and his reflections on his military service.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?