| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

In an effort to stimulate the economy in the midst of the economic depression, Congress passed several acts modifying land sales. The Land Law of 1820 lowered the price of land to $1.25 per acre and allowed small parcels of eighty acres to be sold. The Relief Act of 1821 allowed Ohioans to return land to the government if they could not afford to keep it. The money they received in return was credited toward their debt. The act also extended the credit period to eight years. States, too, attempted to aid those faced with economic hard times by passing laws to prevent mortgage foreclosures so buyers could keep their homes. Americans made the best of the opportunities presented in business, in farming, or on the frontier, and by 1823 the Panic of 1819 had ended. The recovery provided ample evidence of the vibrant and resilient nature of the American people.

The volatility of the U.S. economy did nothing to dampen the creative energies of its citizens in the years before the Civil War. In the 1800s, a frenzy of entrepreneurship and invention yielded many new products and machines. The republic seemed to be a laboratory of innovation, and technological advances appeared unlimited.

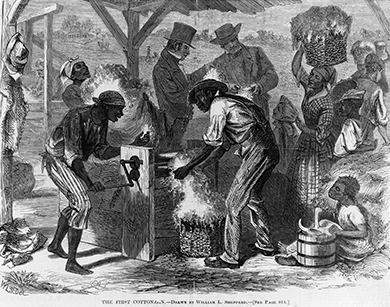

One of the most influential advancements of the early nineteenth century was the cotton engine or gin, invented by Eli Whitney and patented in 1794. Whitney, who was born in Massachusetts, had spent time in the South and knew that a device to speed up the production of cotton was desperately needed so cotton farmers could meet the growing demand for their crop. He hoped the cotton gin would render slavery obsolete. Whitney’s seemingly simple invention cleaned the seeds from the raw cotton far more quickly and efficiently than could slaves working by hand ( [link] ). The raw cotton with seeds was placed in the cotton gin, and with the use of a hand crank, the seeds were extracted through a carding device that aligned the cotton fibers in strands for spinning.

Whitney also worked on machine tools , devices that cut and shaped metal to make standardized, interchangeable parts for other mechanical devices like clocks and guns. Whitney’s machine tools to manufacture parts for muskets enabled guns to be manufactured and repaired by people other than skilled gunsmiths. His creative genius served as a source of inspiration for many other American inventors.

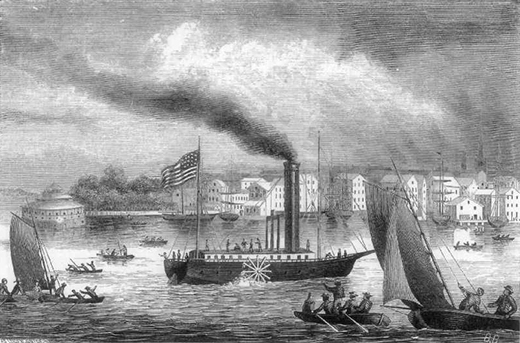

Another influential new technology of the early 1800s was the steamship engine, invented by Robert Fulton in 1807. Fulton’s first steamship, the Clermont , used paddle wheels to travel the 150 miles from New York City to Albany in a record time of only thirty-two hours ( [link] ). Soon, a fleet of steamboats was traversing the Hudson River and New York Harbor, later expanding to travel every major American river including the mighty Mississippi. By the 1830s there were over one thousand of these vessels, radically changing water transportation by ending its dependence on the wind. Steamboats could travel faster and more cheaply than sailing vessels or keelboats, which floated downriver and had to be poled or towed upriver on the return voyage. Steamboats also arrived with much greater dependability. The steamboat facilitated the rapid economic development of the massive Mississippi River Valley and the settlement of the West.

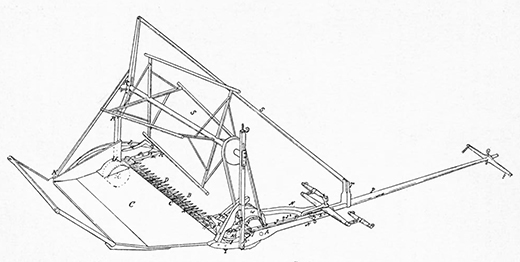

Virginia-born Cyrus McCormick wanted to replace the laborious process of using a scythe to cut and gather wheat for harvest. In 1831, he and the slaves on his family’s plantation tested a horse-drawn mechanical reaper, and over the next several decades, he made constant improvements to it ( [link] ). More farmers began using it in the 1840s, and greater demand for the McCormick reaper led McCormick and his brother to establish the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company in Chicago, where labor was more readily available. By the 1850s, McCormick’s mechanical reaper had enabled farmers to vastly increase their output. McCormick—and also John Deere, who improved on the design of plows—opened the prairies to agriculture. McCormick’s bigger machine could harvest grain faster, and Deere’s plow could cut through the thick prairie sod. Agriculture north of the Ohio River became the pantry that would lower food prices and feed the major cities in the East. In short order, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois all become major agricultural states.

Samuel Morse added the telegraph to the list of American innovations introduced in the years before the Civil War. Born in Massachusetts in 1791, Morse first gained renown as a painter before turning his attention to the development of a method of rapid communication in the 1830s. In 1838, he gave the first public demonstration of his method of conveying electric pulses over a wire, using the basis of what became known as Morse code. In 1843, Congress agreed to help fund the new technology by allocating $30,000 for a telegraph line to connect Washington, DC, and Baltimore along the route of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. In 1844, Morse sent the first telegraph message on the new link. Improved communication systems fostered the development of business, economics, and politics by allowing for dissemination of news at a speed previously unknown.

The selling of the public domain was one of the key features of the early nineteenth century in the United States. Thousands rushed west to take part in the bounty. In the wild frenzy of land purchases and speculation in land, state banks advanced risky loans and created unstable paper money not backed by gold or silver, ultimately leading to the Panic of 1819. The ensuing economic depression was the first in U.S. history. Recovery came in the 1820s, followed by a period of robust growth. In this age of entrepreneurship, in which those who invested their money wisely in land, business ventures, or technological improvements reaped vast profits, inventors produced new wonders that transformed American life.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?