| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The colonies’ alliance with France, secured after the victory at Saratoga in 1777, proved crucial in their victory against the British, and during the 1780s France and the new United States enjoyed a special relationship. Together they had defeated their common enemy, Great Britain. But despite this shared experience, American opinions regarding France diverged sharply in the 1790s when France underwent its own revolution. Democratic-Republicans seized on the French revolutionaries’ struggle against monarchy as the welcome harbinger of a larger republican movement around the world. To the Federalists, however, the French Revolution represented pure anarchy, especially after the execution of the French king in 1793. Along with other foreign and domestic uprisings, the French Revolution helped harden the political divide in the United States in the early 1790s.

The French Revolution, which began in 1789, further split American thinkers into different ideological camps, deepening the political divide between Federalists and their Democratic-Republican foes. At first, in 1789 and 1790, the revolution in France appeared to most in the United States as part of a new chapter in the rejection of corrupt monarchy, a trend inspired by the American Revolution. A constitutional monarchy replaced the absolute monarchy of Louis XVI in 1791, and in 1792, France was declared a republic. Republican liberty, the creed of the United States, seemed to be ushering in a new era in France. Indeed, the American Revolution served as an inspiration for French revolutionaries.

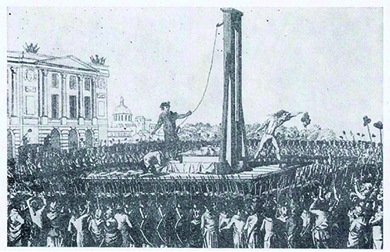

The events of 1793 and 1794 challenged the simple interpretation of the French Revolution as a happy chapter in the unfolding triumph of republican government over monarchy. The French king was executed in January 1793 ( [link] ), and the next two years became known as the Terror , a period of extreme violence against perceived enemies of the revolutionary government. Revolutionaries advocated direct representative democracy, dismantled Catholicism, replaced that religion with a new philosophy known as the Cult of the Supreme Being, renamed the months of the year, and relentlessly employed the guillotine against their enemies. Federalists viewed these excesses with growing alarm, fearing that the radicalism of the French Revolution might infect the minds of citizens at home. Democratic-Republicans interpreted the same events with greater optimism, seeing them as a necessary evil of eliminating the monarchy and aristocratic culture that supported the privileges of a hereditary class of rulers.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?