| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The Daughters’ non-importation movement broadened the protest against the Stamp Act, giving women a new and active role in the political dissent of the time. Women were responsible for purchasing goods for the home, so by exercising the power of the purse, they could wield more power than they had in the past. Although they could not vote, they could mobilize others and make a difference in the political landscape.

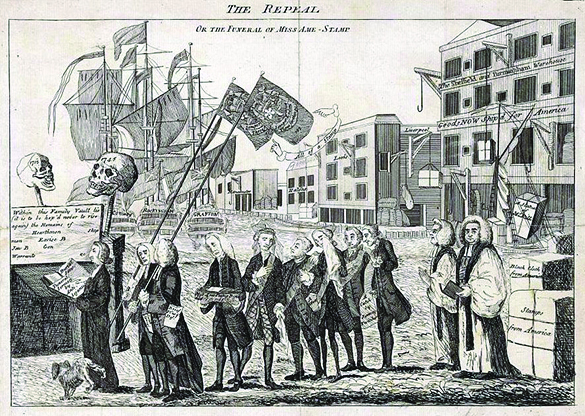

From a local movement, the protests of the Sons and Daughters of Liberty soon spread until there was a chapter in every colony. The Daughters of Liberty promoted the boycott on British goods while the Sons enforced it, threatening retaliation against anyone who bought imported goods or used stamped paper. In the protest against the Stamp Act, wealthy, lettered political figures like John Adams supported the goals of the Sons and Daughters of Liberty, even if they did not engage in the Sons’ violent actions. These men, who were lawyers, printers, and merchants, ran a propaganda campaign parallel to the Sons’ campaign of violence. In newspapers and pamphlets throughout the colonies, they published article after article outlining the reasons the Stamp Act was unconstitutional and urging peaceful protest. They officially condemned violent actions but did not have the protesters arrested; a degree of cooperation prevailed, despite the groups’ different economic backgrounds. Certainly, all the protesters saw themselves as acting in the best British tradition, standing up against the corruption (especially the extinguishing of their right to representation) that threatened their liberty ( [link] ).

Back in Great Britain, news of the colonists’ reactions worsened an already volatile political situation. Grenville’s imperial reforms had brought about increased domestic taxes and his unpopularity led to his dismissal by King George III. While many in Parliament still wanted such reforms, British merchants argued strongly for their repeal. These merchants had no interest in the philosophy behind the colonists’ desire for liberty; rather, their motive was that the non-importation of British goods by North American colonists was hurting their business. Many of the British at home were also appalled by the colonists’ violent reaction to the Stamp Act. Other Britons cheered what they saw as the manly defense of liberty by their counterparts in the colonies.

In March 1766, the new prime minister, Lord Rockingham, compelled Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act. Colonists celebrated what they saw as a victory for their British liberty; in Boston, merchant John Hancock treated the entire town to drinks. However, to appease opponents of the repeal, who feared that it would weaken parliamentary power over the American colonists, Rockingham also proposed the Declaratory Act. This stated in no uncertain terms that Parliament’s power was supreme and that any laws the colonies may have passed to govern and tax themselves were null and void if they ran counter to parliamentary law.

Visit USHistory.org to read the full text of the Declaratory Act, in which Parliament asserted the supremacy of parliamentary power.

Though Parliament designed the 1765 Stamp Act to deal with the financial crisis in the Empire, it had unintended consequences. Outrage over the act created a degree of unity among otherwise unconnected American colonists, giving them a chance to act together both politically and socially. The crisis of the Stamp Act allowed colonists to loudly proclaim their identity as defenders of British liberty. With the repeal of the Stamp Act in 1766, liberty-loving subjects of the king celebrated what they viewed as a victory.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?