| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

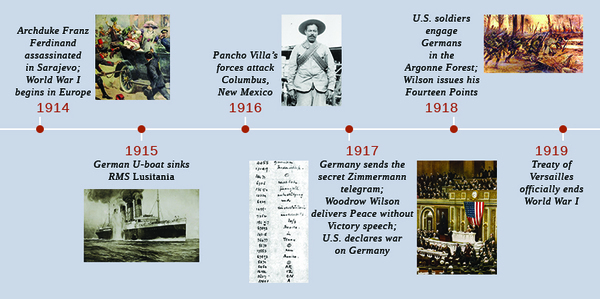

Unlike his immediate predecessors, President Woodrow Wilson had planned to shrink the role of the United States in foreign affairs. He believed that the nation needed to intervene in international events only when there was a moral imperative to do so. But as Europe’s political situation grew dire, it became increasingly difficult for Wilson to insist that the conflict growing overseas was not America’s responsibility. Germany’s war tactics struck most observers as morally reprehensible, while also putting American free trade with the Entente at risk. Despite campaign promises and diplomatic efforts, Wilson could only postpone American involvement in the war.

When Woodrow Wilson took over the White House in March 1913, he promised a less expansionist approach to American foreign policy than Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft had pursued. Wilson did share the commonly held view that American values were superior to those of the rest of the world, that democracy was the best system to promote peace and stability, and that the United States should continue to actively pursue economic markets abroad. But he proposed an idealistic foreign policy based on morality, rather than American self-interest, and felt that American interference in another nation’s affairs should occur only when the circumstances rose to the level of a moral imperative.

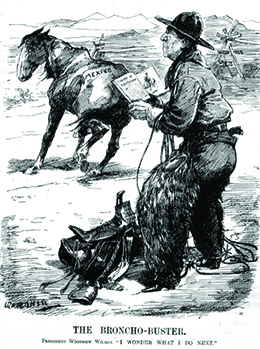

Wilson appointed former presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, a noted anti-imperialist and proponent of world peace, as his Secretary of State. Bryan undertook his new assignment with great vigor, encouraging nations around the world to sign “cooling off treaties,” under which they agreed to resolve international disputes through talks, not war, and to submit any grievances to an international commission. Bryan also negotiated friendly relations with Colombia, including a $25 million apology for Roosevelt’s actions during the Panamanian Revolution, and worked to establish effective self-government in the Philippines in preparation for the eventual American withdrawal. Even with Bryan’s support, however, Wilson found that it was much harder than he anticipated to keep the United States out of world affairs ( [link] ). In reality, the United States was interventionist in areas where its interests—direct or indirect—were threatened.

Wilson’s greatest break from his predecessors occurred in Asia, where he abandoned Taft’s “dollar diplomacy,” a foreign policy that essentially used the power of U.S. economic dominance as a threat to gain favorable terms. Instead, Wilson revived diplomatic efforts to keep Japanese interference there at a minimum. But as World War I, also known as the Great War, began to unfold, and European nations largely abandoned their imperialistic interests in order to marshal their forces for self-defense, Japan demanded that China succumb to a Japanese protectorate over their entire nation. In 1917, William Jennings Bryan’s successor as Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, signed the Lansing-Ishii Agreement, which recognized Japanese control over the Manchurian region of China in exchange for Japan’s promise not to exploit the war to gain a greater foothold in the rest of the country.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?