| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

For some in the NAWSA, however, the pace of change was too slow. Frustrated with the lack of response by state and national legislators, Alice Paul, who joined the organization in 1912, sought to expand the scope of the organization as well as to adopt more direct protest tactics to draw greater media attention. When others in the group were unwilling to move in her direction, Paul split from the NAWSA to create the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, later renamed the National Woman’s Party, in 1913. Known as the Silent Sentinels ( [link] ), Paul and her group picketed outside the White House for nearly two years, starting in 1917. In the latter stages of their protests, many women, including Paul, were arrested and thrown in jail, where they staged a hunger strike as self-proclaimed political prisoners. Prison guards ultimately force-fed Paul to keep her alive. At a time—during World War I—when women volunteered as army nurses, worked in vital defense industries, and supported Wilson’s campaign to “make the world safe for democracy,” the scandalous mistreatment of Paul embarrassed President Woodrow Wilson. Enlightened to the injustice toward all American women, he changed his position in support of a woman’s constitutional right to vote.

While Catt and Paul used different strategies, their combined efforts brought enough pressure to bear for Congress to pass the Nineteenth Amendment, which prohibited voter discrimination on the basis of sex, during a special session in the summer of 1919. Subsequently, the required thirty-six states approved its adoption, with Tennessee doing so in August of 1920, in time for that year’s presidential election.

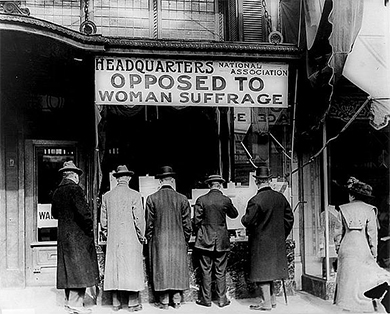

The early suffragists may have believed that the right to vote was a universal one, but they faced waves of discrimination and ridicule from both men and women. The image below ( [link] ) shows one of the organizations pushing back against the suffragist movement, but much of the anti-suffrage campaign was carried out through ridiculing postcards and signs that showed suffragists as sexually wanton, grasping, irresponsible, or impossibly ugly. Men in anti-suffragist posters were depicted as henpecked, crouching to clean the floor, while their suffragist wives marched out the door to campaign for the vote. They also showed cartoons of women gambling, drinking, and smoking cigars, that is, taking on men’s vices, once they gained voting rights.

Other anti-suffragists believed that women could better influence the country from outside the realm of party politics, through their clubs, petitions, and churches. Many women also opposed women’s suffrage because they thought the dirty world of politics was a morass to which ladies should not be exposed. The National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage formed in 1911; around the country, state representatives used the organization’s speakers, funds, and literature to promote the anti-suffragist cause. As the link below illustrates, the suffragists endured much prejudice and backlash in their push for equal rights.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?