| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

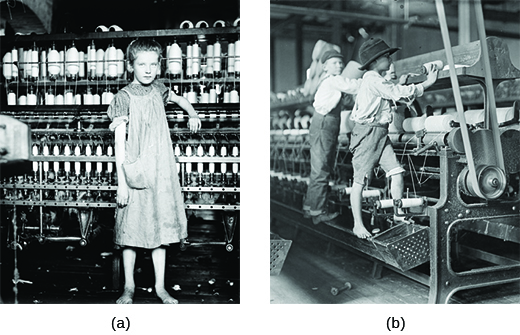

Building on the successes of the settlement houses, social justice reformers took on other, related challenges. The National Child Labor Committee (NCLC), formed in 1904, urged the passage of labor legislation to ban child labor in the industrial sector. In 1900, U.S. census records indicated that one out of every six children between the ages of five and ten were working, a 50-percent increase over the previous decade. If the sheer numbers alone were not enough to spur action, the fact that managers paid child workers noticeably less for their labor gave additional fuel to the NCLC’s efforts to radically curtail child labor. The committee employed photographer Lewis Hine to engage in a decade-long pictorial campaign to educate Americans on the plight of children working in factories ( [link] ).

Although low-wage industries fiercely opposed any federal restriction on child labor, the NCLC did succeed in 1912, urging President William Howard Taft to sign into law the creation of the U.S. Children’s Bureau. As a branch of the Department of Labor, the bureau worked closely with the NCLC to bring greater awareness to the issue of child labor. In 1916, the pressure from the NCLC and the general public resulted in the passage of the Keating-Owen Act, which prohibited the interstate trade of any goods produced with child labor. Although the U.S. Supreme Court later declared the law unconstitutional, Keating-Owen reflected a significant shift in the public perception of child labor. Finally, in 1938, the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act signaled the victory of supporters of Keating-Owen. This new law outlawed the interstate trade of any products produced by children under the age of sixteen.

Florence Kelley, a Progressive supporter of the NCLC, championed other social justice causes as well. As the first general secretary of the National Consumers League, which was founded in 1899 by Jane Addams and others, Kelley led one of the original battles to try and secure safety in factory working conditions. She particularly opposed sweatshop labor and urged the passage of an eight-hour-workday law in order to specifically protect women in the workplace. Kelley’s efforts were initially met with strong resistance from factory owners who exploited women’s labor and were unwilling to give up the long hours and low wages they paid in order to offer the cheapest possible product to consumers. But in 1911, a tragedy turned the tide of public opinion in favor of Kelley’s cause. On March 25 of that year, a fire broke out at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company on the eighth floor of the Asch building in New York City, resulting in the deaths of 146 garment workers, most of them young, immigrant women ( [link] ). Management had previously blockaded doors and fire escapes in an effort to control workers and keep out union organizers; in the blaze, many died due to the crush of bodies trying to evacuate the building. Others died when they fell off the flimsy fire escape or jumped to their deaths to escape the flames. This tragedy provided the National Consumers League with the moral argument to convince politicians of the need to pass workplace safety laws and codes.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?