| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Although Hayes’ questionable ascendancy to the presidency did not create political corruption in the nation’s capital, it did set the stage for politically motivated agendas and widespread inefficiency in the White House for the next twenty-four years. Weak president after weak president took office, and, as mentioned above, not one incumbent was reelected. The populace, it seemed, preferred the devil they didn’t know to the one they did. Once elected, presidents had barely enough power to repay the political favors they owed to the individuals who ensured their narrow victories in cities and regions around the country. Their four years in office were spent repaying favors and managing the powerful relationships that put them in the White House. Everyday Americans were largely left on their own. Among the few political issues that presidents routinely addressed during this era were ones of patronage, tariffs, and the nation’s monetary system.

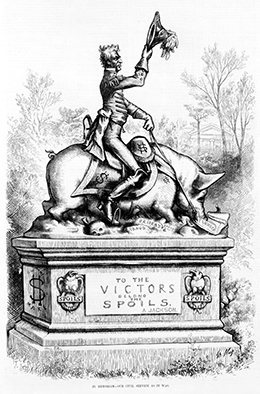

At the heart of each president’s administration was the protection of the spoils system, that is, the power of the president to practice widespread political patronage. Patronage, in this case, took the form of the president naming his friends and supporters to various political posts. Given the close calls in presidential elections during the era, the maintenance of political machinery and repaying favors with patronage was important to all presidents, regardless of party affiliation. This had been the case since the advent of a two-party political system and universal male suffrage in the Jacksonian era. For example, upon assuming office in March 1829, President Jackson immediately swept employees from over nine hundred political offices, amounting to 10 percent of all federal appointments. Among the hardest-hit was the U.S. Postal Service, which saw Jackson appoint his supporters and closest friends to over four hundred positions in the service ( [link] ).

As can be seen in the table below ( [link] ), every single president elected from 1876 through 1892 won despite receiving less than 50 percent of the popular vote. This established a repetitive cycle of relatively weak presidents who owed many political favors, which could be repaid through one prerogative power: patronage. As a result, the spoils system allowed those with political influence to ascend to powerful positions within the government, regardless of their level of experience or skill, thus compounding both the inefficiency of government as well as enhancing the opportunities for corruption.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?