| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Seeking still more control, Rockefeller recognized the advantages of controlling the transportation of his product. He next began to grow his company through vertical integration , wherein a company handles all aspects of a product’s lifecycle, from the creation of raw materials through the production process to the delivery of the final product. In Rockefeller’s case, this model required investment and acquisition of companies involved in everything from barrel-making to pipelines, tanker cars to railroads. He came to own almost every type of business and used his vast power to drive competitors from the market through intense price wars. Although vilified by competitors who suffered from his takeovers and considered him to be no better than a robber baron, several observers lauded Rockefeller for his ingenuity in integrating the oil refining industry and, as a result, lowering kerosene prices by as much as 80 percent by the end of the century. Other industrialists quickly followed suit, including Gustavus Swift, who used vertical integration to dominate the U.S. meatpacking industry in the late nineteenth century.

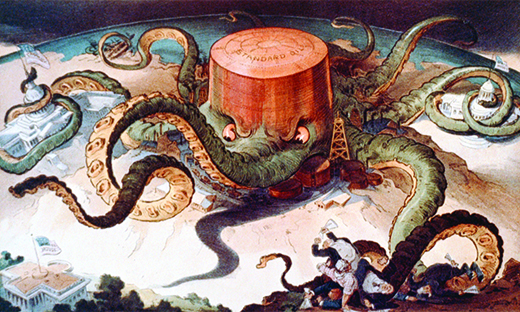

In order to control the variety of interests he now maintained in industry, Rockefeller created a new legal entity, known as a trust . In this arrangement, a small group of trustees possess legal ownership of a business that they operate for the benefit of other investors. In 1882, all thirty-seven stockholders in the various Standard Oil enterprises gave their stock to nine trustees who were to control and direct all of the company’s business ventures. State and federal challenges arose, due to the obvious appearance of a monopoly, which implied sole ownership of all enterprises composing an entire industry. When the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that the Standard Oil Company must dissolve, as its monopoly control over all refining operations in the U.S. was in violation of state and federal statutes, Rockefeller shifted to yet another legal entity, called a holding company model. The holding company model created a central corporate entity that controlled the operations of multiple companies by holding the majority of stock for each enterprise. While not technically a “trust” and therefore not vulnerable to anti-monopoly laws, this consolidation of power and wealth into one entity was on par with a monopoly; thus, progressive reformers of the late nineteenth century considered holding companies to epitomize the dangers inherent in capitalistic big business, as can be seen in the political cartoon below ( [link] ). Impervious to reformers’ misgivings, other businessmen followed Rockefeller’s example. By 1905, over three hundred business mergers had occurred in the United States, affecting more than 80 percent of all industries. By that time, despite passage of federal legislation such as the Sherman Anti-Trust Act in 1890, 1 percent of the country’s businesses controlled over 40 percent of the nation’s economy.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?