| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

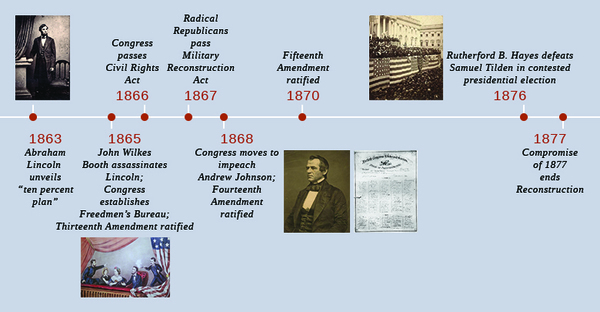

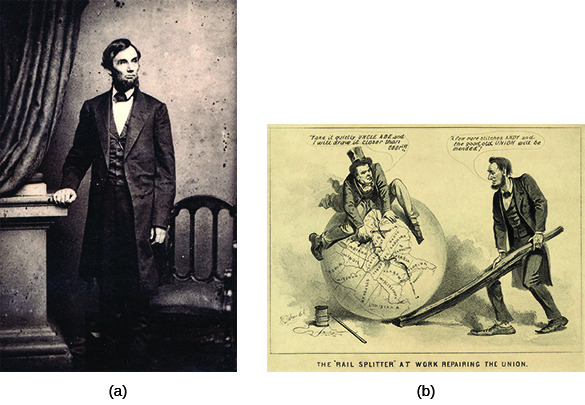

The end of the Civil War saw the beginning of the Reconstruction era, when former rebel Southern states were integrated back into the Union. President Lincoln moved quickly to achieve the war’s ultimate goal: reunification of the country. He proposed a generous and non-punitive plan to return the former Confederate states speedily to the United States, but some Republicans in Congress protested, considering the president’s plan too lenient to the rebel states that had torn the country apart. The greatest flaw of Lincoln’s plan, according to this view, was that it appeared to forgive traitors instead of guaranteeing civil rights to former slaves. President Lincoln oversaw the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, but he did not live to see its ratification.

From the outset of the rebellion in 1861, Lincoln’s overriding goal had been to bring the Southern states quickly back into the fold in order to restore the Union ( [link] ). In early December 1863, the president began the process of reunification by unveiling a three-part proposal known as the ten percent plan that outlined how the states would return. The ten percent plan gave a general pardon to all Southerners except high-ranking Confederate government and military leaders; required 10 percent of the 1860 voting population in the former rebel states to take a binding oath of future allegiance to the United States and the emancipation of slaves; and declared that once those voters took those oaths, the restored Confederate states would draft new state constitutions.

Lincoln hoped that the leniency of the plan—90 percent of the 1860 voters did not have to swear allegiance to the Union or to emancipation—would bring about a quick and long-anticipated resolution and make emancipation more acceptable everywhere. This approach appealed to some in the moderate wing of the Republican Party, which wanted to put the nation on a speedy course toward reconciliation. However, the proposal instantly drew fire from a larger faction of Republicans in Congress who did not want to deal moderately with the South. These members of Congress, known as Radical Republicans , wanted to remake the South and punish the rebels. Radical Republicans insisted on harsh terms for the defeated Confederacy and protection for former slaves, going far beyond what the president proposed.

In February 1864, two of the Radical Republicans, Ohio senator Benjamin Wade and Maryland representative Henry Winter Davis, answered Lincoln with a proposal of their own. Among other stipulations, the Wade-Davis Bill called for a majority of voters and government officials in Confederate states to take an oath, called the Ironclad Oath , swearing that they had never supported the Confederacy or made war against the United States. Those who could not or would not take the oath would be unable to take part in the future political life of the South. Congress assented to the Wade-Davis Bill, and it went to Lincoln for his signature. The president refused to sign, using the pocket veto (that is, taking no action) to kill the bill. Lincoln understood that no Southern state would have met the criteria of the Wade-Davis Bill, and its passage would simply have delayed the reconstruction of the South.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?