| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Many settlers in the United States found themselves on this continent as refugees from such wars; others came to find a place where they could follow their own religion with like-minded people in relative peace. So as a practical matter, even if the early United States had wanted to establish a single national religion, the diversity of religious beliefs would already have prevented it. Nonetheless the differences were small; most people were of European origin and professed some form of Christianity (although in private some of the founders, most notably Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, and Benjamin Franklin, held what today would be seen as Unitarian and/or deistic views). So for much of U.S. history, the establishment clause was not particularly important—the vast majority of citizens were Protestant Christians of some form, and since the federal government was relatively uninvolved in the day-to-day lives of the people, there was little opportunity for conflict. That said, there were some citizenship and office-holding restrictions on Jews within some of the states.

Worry about state sponsorship of religion in the United States began to reemerge in the latter part of the nineteenth century. An influx of immigrants from Ireland and eastern and southern Europe brought large numbers of Catholics, and states—fearing the new immigrants and their children would not assimilate—passed laws forbidding government aid to religious schools. New religious organizations, such as the Church of Latter-day Saints (the Mormon Church), Seventh-day Adventists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and many others, also emerged, blending aspects of Protestant beliefs with other ideas and teachings at odds with the more traditional Protestant churches of the era. At the same time, public schooling was beginning to take root on a wide scale. Since most states had traditional Protestant majorities and most state officials were Protestants themselves, the public school curriculum incorporated many Protestant features; at times, these features would come into conflict with the beliefs of children from other Christian sects or from other religious traditions.

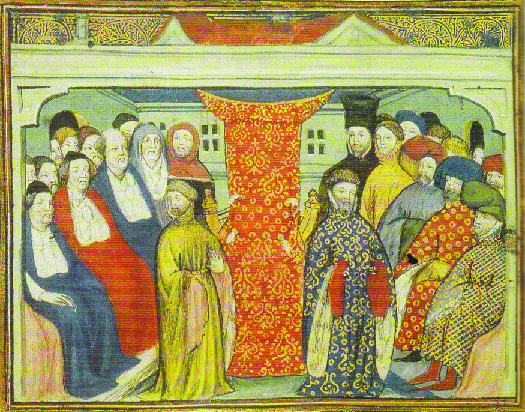

The establishment clause today tends to be interpreted a bit more broadly than in the past; it not only forbids the creation of a “Church of the United States” or “Church of Ohio” it also forbids the government from favoring one set of religious beliefs over others or favoring religion (of any variety) over non-religion. Thus, the government cannot promote, say, Islamic beliefs over Sikh beliefs or belief in God over atheism or agnosticism ( [link] ).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'American government' conversation and receive update notifications?