| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

With the onset of the

Great Depression in 1929, the United States faced record levels of unemployment and the associated fall into poverty, food shortages, and general desperation. When the Republican president and Congress were not seen as moving aggressively enough to fix the situation, the Democrats won the 1932 election in overwhelming fashion. President Franklin D.

Roosevelt and the U.S. Congress rapidly reorganized the government’s problem-solving efforts into a series of programs designed to revive the economy, stimulate economic development, and generate employment opportunities. In the 1930s, the federal bureaucracy grew with the addition of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to protect and regulate U.S. banking, the National Labor Relations Board to regulate the way companies could treat their workers, the Securities and Exchange Commission to regulate the stock market, and the Civil Aeronautics Board to regulate air travel. Additional programs and institutions emerged with the Social Security Administration in 1935 and then, during World War II, various wartime boards and agencies. By 1940, approximately 700,000 U.S. workers were employed in the federal bureaucracy.

Under President Lyndon B.

Johnson in the 1960s, that number reached 2.2 million, and the federal budget increased to $332 billion.

All of these new programs required bureaucrats to run them, and the national bureaucracy naturally ballooned. Its size became a rallying cry for conservatives, who eventually elected Ronald

Reagan president for the express purpose of reducing the bureaucracy. While Reagan was able to work with Congress to reduce some aspects of the federal bureaucracy, he contributed to its expansion in other ways, particularly in his efforts to fight the Cold War.

The two periods of increased bureaucratic growth in the United States, the 1930s and the 1960s, accomplished far more than expanding the size of government. They transformed politics in ways that continue to shape political debate today. While the bureaucracies created in these two periods served important purposes, many at that time and even now argue that the expansion came with unacceptable costs, particularly economic costs. The common argument that bureaucratic regulation smothers capitalist innovation was especially powerful in the Cold War environment of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. But as long as voters felt they were benefiting from the bureaucratic expansion, as they typically did, the political winds supported continued growth.

In the 1970s, however, Germany and Japan were thriving economies in positions to compete with U.S. industry. This competition, combined with technological advances and the beginnings of computerization, began to eat away at American prosperity. Factories began to close, wages began to stagnate, inflation climbed, and the future seemed a little less bright. In this environment, tax-paying workers were less likely to support generous welfare programs designed to end poverty. They felt these bureaucratic programs were adding to their misery in order to support unknown others.

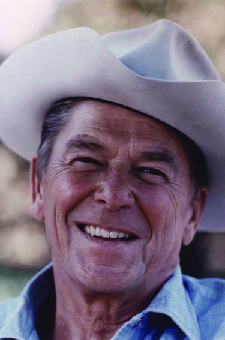

In his first and unsuccessful presidential bid in 1976, Ronald Reagan, a skilled politician and governor of California, stoked working-class anxieties by directing voters’ discontent at the bureaucratic dragon he proposed to slay. When he ran again four years later, his criticism of bureaucratic waste in Washington carried him to a landslide victory. While it is debatable whether Reagan actually reduced the size of government, he continued to wield rhetoric about bureaucratic waste to great political advantage. Even as late as 1986, he continued to rail against the Washington bureaucracy ( [link] ), once declaring famously that “the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.”

Why might people be more sympathetic to bureaucratic growth during periods of prosperity? In what way do modern politicians continue to stir up popular animosity against bureaucracy to political advantage? Is it effective? Why or why not?

During the post-Jacksonian era of the nineteenth century, the common charge against the bureaucracy was that it was overly political and corrupt. This changed in the 1880s as the United States began to create a modern civil service. The civil service grew once again in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration as he expanded government programs to combat the effects of the Great Depression. The most recent criticisms of the federal bureaucracy, notably under Ronald Reagan, emerged following the second great expansion of the federal government under Lyndon B Johnson in the 1960s.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'American government' conversation and receive update notifications?