| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

As the velocity of M1 began to fluctuate in the 1980s, having the money supply grow at a predetermined and unchanging rate seemed less desirable, because as the quantity theory of money shows, the combination of constant growth in the money supply and fluctuating velocity would cause nominal GDP to rise and fall in unpredictable ways. The jumpiness of velocity in the 1980s caused many central banks to focus less on the rate at which the quantity of money in the economy was increasing, and instead to set monetary policy by reacting to whether the economy was experiencing or in danger of higher inflation or unemployment.

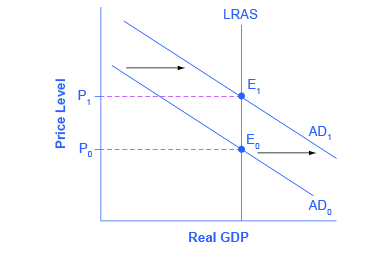

If you were to survey central bankers around the world and ask them what they believe should be the primary task of monetary policy, the most popular answer by far would be fighting inflation. Most central bankers believe that the neoclassical model of economics accurately represents the economy over the medium to long term. Remember that in the neoclassical model of the economy, the aggregate supply curve is drawn as a vertical line at the level of potential GDP, as shown in [link] . In the neoclassical model, the level of potential GDP (and the natural rate of unemployment that exists when the economy is producing at potential GDP) is determined by real economic factors. If the original level of aggregate demand is AD 0 , then an expansionary monetary policy that shifts aggregate demand to AD 1 only creates an inflationary increase in the price level, but it does not alter GDP or unemployment. From this perspective, all that monetary policy can do is to lead to low inflation or high inflation—and low inflation provides a better climate for a healthy and growing economy. After all, low inflation means that businesses making investments can focus on real economic issues, not on figuring out ways to protect themselves from the costs and risks of inflation. In this way, a consistent pattern of low inflation can contribute to long-term growth.

This vision of focusing monetary policy on a low rate of inflation is so attractive that many countries have rewritten their central banking laws since in the 1990s to have their bank practice inflation targeting , which means that the central bank is legally required to focus primarily on keeping inflation low. By 2014, central banks in 28 countries, including Austria, Brazil, Canada, Israel, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Spain, Sweden, Thailand, and the United Kingdom faced a legal requirement to target the inflation rate. A notable exception is the Federal Reserve in the United States, which does not practice inflation-targeting. Instead, the law governing the Federal Reserve requires it to take both unemployment and inflation into account.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of economics' conversation and receive update notifications?