| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

| The U.S. Economy, after Specialization, Will Benefit If It: | The Saudi Arabian Economy, after Specialization, Will Benefit If It: |

|---|---|

| Exports no more than 60 bushels of corn | Imports at least 10 bushels of corn |

| Imports at least 20 barrels of oil | Exports less than 60 barrels of oil |

The underlying reason why trade benefits both sides is rooted in the concept of opportunity cost, as the following Clear It Up feature explains. If Saudi Arabia wishes to expand domestic production of corn in a world without international trade, then based on its opportunity costs it must give up four barrels of oil for every one additional bushel of corn. If Saudi Arabia could find a way to give up less than four barrels of oil for an additional bushel of corn (or equivalently, to receive more than one bushel of corn for four barrels of oil), it would be better off.

The range of trades that will benefit each country is based on the country’s opportunity cost of producing each good. The United States can produce 100 bushels of corn or 50 barrels of oil. For the United States, the opportunity cost of producing one barrel of oil is two bushels of corn. If we divide the numbers above by 50, we get the same ratio: one barrel of oil is equivalent to two bushels of corn, or (100/50 = 2 and 50/50 = 1). In a trade with Saudi Arabia, if the United States is going to give up 100 bushels of corn in exports, it must import at least 50 barrels of oil to be just as well off. Clearly, to gain from trade it needs to be able to gain more than a half barrel of oil for its bushel of corn—or why trade at all?

Recall that David Ricardo argued that if each country specializes in its comparative advantage, it will benefit from trade, and total global output will increase. How can we show gains from trade as a result of comparative advantage and specialization? [link] shows the output assuming that each country specializes in its comparative advantage and produces no other good. This is 100% specialization. Specialization leads to an increase in total world production. (Compare the total world production in [link] to that in [link] .)

| Country | Quantity produced after 100% specialization — Oil (barrels) | Quantity produced after 100% specialization — Corn (bushels) |

|---|---|---|

| Saudi Arabia | 100 | 0 |

| United States | 0 | 100 |

| Total World Production | 100 | 100 |

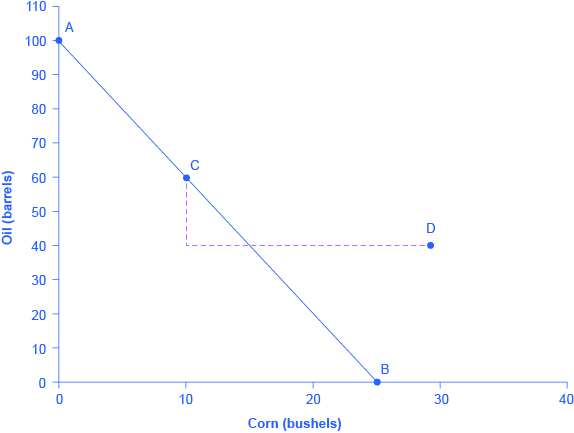

What if we did not have complete specialization, as in [link] ? Would there still be gains from trade? Consider another example, such as when the United States and Saudi Arabia start at C and C', respectively, as shown in [link] . Consider what occurs when trade is allowed and the United States exports 20 bushels of corn to Saudi Arabia in exchange for 20 barrels of oil.

Starting at point C, reduce Saudi Oil production by 20 and exchange it for 20 units of corn to reach point D (see [link] ). Notice that even without 100% specialization, if the “trading price,” in this case 20 barrels of oil for 20 bushels of corn, is greater than the country’s opportunity cost, the Saudis will gain from trade. Indeed both countries consume more of both goods after specialized production and trade occurs.

Visit this website for trade-related data visualizations.

A country has an absolute advantage in those products in which it has a productivity edge over other countries; it takes fewer resources to produce a product. A country has a comparative advantage when a good can be produced at a lower cost in terms of other goods. Countries that specialize based on comparative advantage gain from trade.

France and Tunisia both have Mediterranean climates that are excellent for producing/harvesting green beans and tomatoes. In France it takes two hours for each worker to harvest green beans and two hours to harvest a tomato. Tunisian workers need only one hour to harvest the tomatoes but four hours to harvest green beans. Assume there are only two workers, one in each country, and each works 40 hours a week.

Krugman, Paul R. Pop Internationalism . The MIT Press, Cambridge. 1996.

Krugman, Paul R. “What Do Undergrads Need to Know about Trade?” American Economic Review 83, no. 2. 1993. 23-26.

Ricardo, David. On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation . London: John Murray, 1817.

Ricardo, David. “On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation.” Library of Economics and Liberty. http://www.econlib.org/library/Ricardo/ricP.html.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of economics' conversation and receive update notifications?