| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

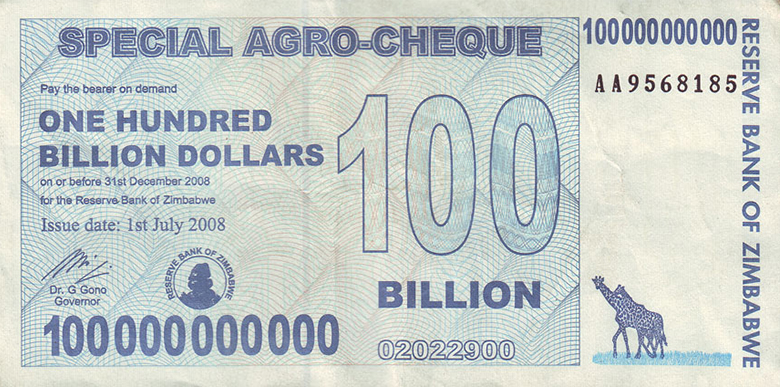

If you were born within the last three decades in the United States, Canada, or many other countries in the developed world, you probably have no real experience with a high rate of inflation. Inflation is when most prices in an entire economy are rising. But there is an extreme form of inflation called hyperinflation. This occurred in Germany between 1921 and 1928, and more recently in Zimbabwe between 2008 and 2009. In November of 2008, Zimbabwe had an inflation rate of 79.6 billion percent. In contrast, in 2014, the United States had an average annual rate of inflation of 1.6%.

Zimbabwe’s inflation rate was so high it is difficult to comprehend. So, let’s put it into context. It is equivalent to price increases of 98% per day. This means that, from one day to the next, prices essentially double. What is life like in an economy afflicted with hyperinflation? Not like anything you are familiar with. Prices for commodities in Zimbabwean dollars were adjusted several times each day . There was no desire to hold on to currency since it lost value by the minute. The people there spent a great deal of time getting rid of any cash they acquired by purchasing whatever food or other commodities they could find. At one point, a loaf of bread cost 550 million Zimbabwean dollars. Teachers were paid in the trillions a month; however this was equivalent to only one U.S. dollar a day. At its height, it took 621,984,228 Zimbabwean dollars to purchase one U.S. dollar.

Government agencies had no money to pay their workers so they started printing money to pay their bills rather than raising taxes. Rising prices caused the government to enact price controls on private businesses, which led to shortages and the emergence of black markets. In 2009, the country abandoned its currency and allowed foreign currencies to be used for purchases.

How does this happen? How can both government and the economy fail to function at the most basic level? Before we consider these extreme cases of hyperinflation, let’s first look at inflation itself.

In this chapter, you will learn about:

Inflation is a general and ongoing rise in the level of prices in an entire economy. Inflation does not refer to a change in relative prices. A relative price change occurs when you see that the price of tuition has risen, but the price of laptops has fallen. Inflation, on the other hand, means that there is pressure for prices to rise in most markets in the economy. In addition, price increases in the supply-and-demand model were one-time events, representing a shift from a previous equilibrium to a new one. Inflation implies an ongoing rise in prices. If inflation happened for one year and then stopped—well, then it would not be inflation any more.

This chapter begins by showing how to combine prices of individual goods and services to create a measure of overall inflation. It discusses the historical and recent experience of inflation, both in the United States and in other countries around the world. Other chapters have sometimes included a note under an exhibit or a parenthetical reminder in the text saying that the numbers have been adjusted for inflation. In this chapter, it is time to show how to use inflation statistics to adjust other economic variables, so that you can tell how much of, say, the rise in GDP over different periods of time can be attributed to an actual increase in the production of goods and services and how much should be attributed to the fact that prices for most things have risen.

Inflation has consequences for people and firms throughout the economy, in their roles as lenders and borrowers, wage-earners, taxpayers, and consumers. The chapter concludes with a discussion of some imperfections and biases in the inflation statistics, and a preview of policies for fighting inflation that will be discussed in other chapters.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of economics' conversation and receive update notifications?