| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Some modern economists have argued in a Keynesian spirit that, along with wages, other prices may be sticky, too. Many firms do not change their prices every day or even every month. When a firm considers changing prices, it must consider two sets of costs. First, changing prices uses company resources: managers must analyze the competition and market demand and decide what the new prices will be, sales materials must be updated, billing records will change, and product labels and price labels must be redone. Second, frequent price changes may leave customers confused or angry—especially if they find out that a product now costs more than expected. These costs of changing prices are called menu costs —like the costs of printing up a new set of menus with different prices in a restaurant. Prices do respond to forces of supply and demand, but from a macroeconomic perspective, the process of changing all prices throughout the economy takes time.

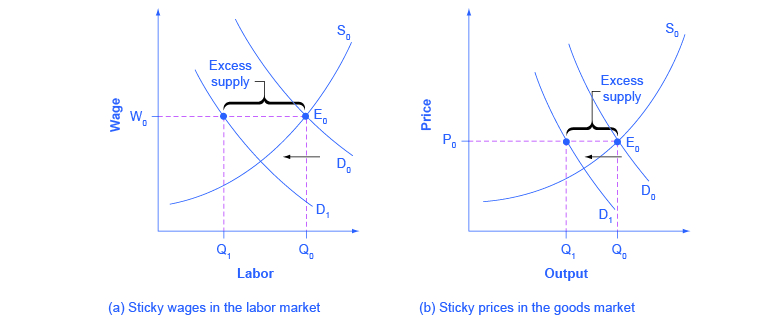

To understand the effect of sticky wages and prices in the economy, consider [link] (a) illustrating the overall labor market, while [link] (b) illustrates a market for a specific good or service. The original equilibrium (E 0 ) in each market occurs at the intersection of the demand curve (D 0 ) and supply curve (S 0 ). When aggregate demand declines, the demand for labor shifts to the left (to D 1 ) in [link] (a) and the demand for goods shifts to the left (to D 1 ) in [link] (b). However, because of sticky wages and prices, the wage remains at its original level (W 0 ) for a period of time and the price remains at its original level (P 0 ).

As a result, a situation of excess supply—where the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded at the existing wage or price—exists in markets for both labor and goods, and Q 1 is less than Q 0 in both [link] (a) and [link] (b). When many labor markets and many goods markets all across the economy find themselves in this position, the economy is in a recession; that is, firms cannot sell what they wish to produce at the existing market price and do not wish to hire all who are willing to work at the existing market wage. The Clear It Up feature discusses this problem in more detail.

The recovery after the Great Recession in the United States has been slow, with wages stagnant, if not declining. In fact, many low-wage workers at McDonalds, Dominos, and Walmart have threatened to strike for higher wages. Their plight is part of a larger trend in job growth and pay in the post–recession recovery.

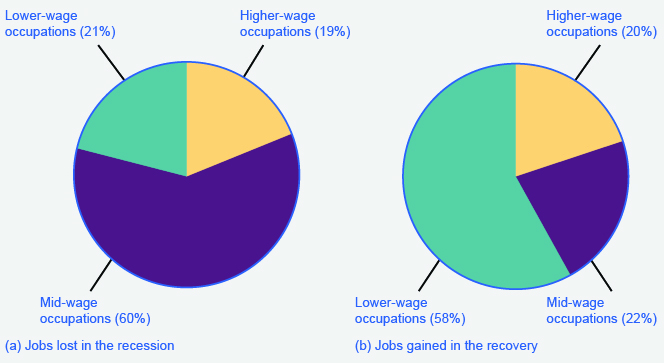

The National Employment Law Project compiled data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and found that, during the Great Recession, 60% of job losses were in medium-wage occupations. Most of them were replaced during the recovery period with lower-wage jobs in the service, retail, and food industries. This data is illustrated in [link] .

Wages in the service, retail, and food industries are at or near minimum wage and tend to be both downwardly and upwardly “sticky.” Wages are downwardly sticky due to minimum wage laws; they may be upwardly sticky if insufficient competition in low-skilled labor markets enables employers to avoid raising wages that would reduce their profits. At the same time, however, the Consumer Price Index increased 11% between 2007 and 2012, pushing real wages down.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of economics' conversation and receive update notifications?