| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

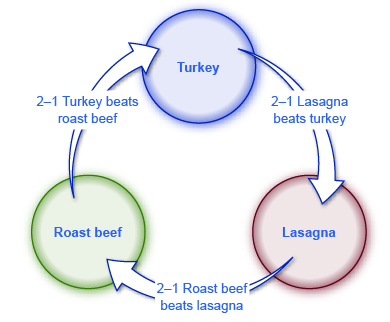

Clearly, the three families disagree on their first choice. But the problem goes even deeper. Instead of looking at all three choices at once, compare them two at a time. (See [link] ) In a vote of turkey versus beef, turkey wins by 2–1. In a vote of beef versus lasagna, beef wins 2–1. If turkey beats beef, and beef beats lasagna, then it might seem only logical that turkey must also beat lasagna. However, with the preferences shown, lasagna is preferred to turkey by a 2–1 vote, as well. If lasagna is preferred to turkey, and turkey beats beef, then surely it must be that lasagna also beats beef? Actually, no; beef beats lasagna. In other words, the majority view may not win. Clearly, as any car salesmen will tell you, choices are influenced by the way they are presented.

| The Ortega Family | The Schmidt Family | The Alexander Family | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Choice | Turkey | Roast beef | Lasagna |

| Second Choice | Roast beef | Lasagna | Turkey |

| Third Choice | Lasagna | Turkey | Roast beef |

The situation in which Choice A is preferred by a majority over Choice B, Choice B is preferred by a majority over Choice C, and Choice C is preferred by a majority over Choice A is called a voting cycle . It is easy to imagine sets of government choices—say, perhaps the choice between increased defense spending, increased government spending on health care, and a tax cut—in which a voting cycle could occur. The result will be determined by the order in which choices are presented and voted on, not by majority rule, because every choice is both preferred to some alternative and also not preferred to another alternative.

Visit this website to read about instant runoff voting, a preferential voting system.

When a firm produces a product no one wants to buy or produces at a higher cost than its competitors, the firm is likely to suffer losses. If it cannot change its ways, it will go out of business. This self-correcting mechanism in the marketplace can have harsh effects on workers or on local economies, but it also puts pressure on firms for good performance.

Government agencies, on the other hand, do not sell their products in a market; they receive tax dollars instead. They are not challenged by competitors as are private-sector firms. If the U.S. Department of Education or the U.S. Department of Defense is doing a poor job, citizens cannot purchase their services from another provider and drive the existing government agencies into bankruptcy. If you are upset that the Internal Revenue Service is slow in sending you a tax refund or seems unable to answer your questions, you cannot decide to pay your income taxes through a different organization. Of course, elected politicians can assign new leaders to government agencies and instruct them to reorganize or to emphasize a different mission. The pressure government faces, however, to change its bureaucracy, to seek greater efficiency, and to improve customer responsiveness is much milder than the threat of being put out of business altogether.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of microeconomics for ap® courses' conversation and receive update notifications?