| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

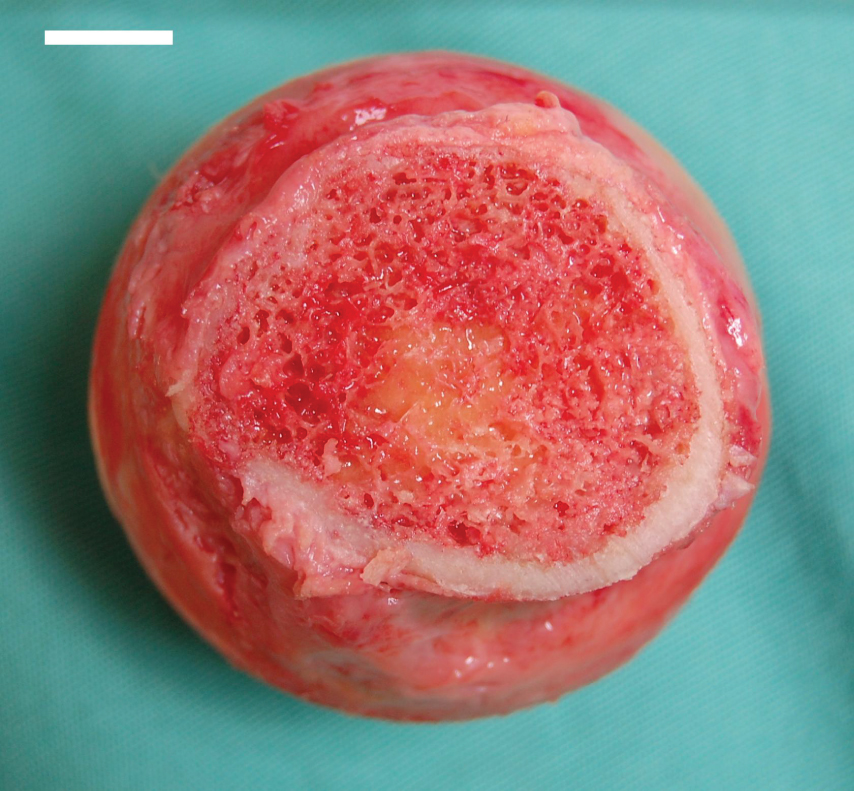

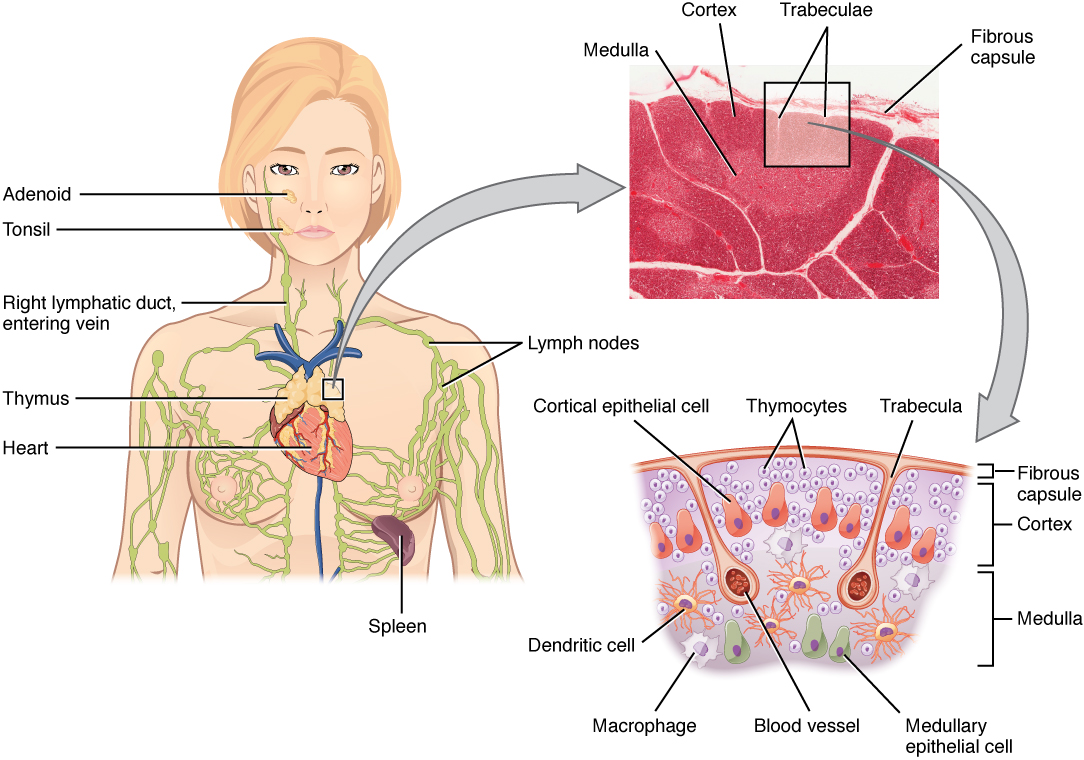

The thymus gland is a bilobed organ found in the space between the sternum and the aorta of the heart ( [link] ). Connective tissue holds the lobes closely together but also separates them and forms a capsule.

View the University of Michigan WebScope at (External Link) to explore the tissue sample in greater detail.

The connective tissue capsule further divides the thymus into lobules via extensions called trabeculae. The outer region of the organ is known as the cortex and contains large numbers of thymocytes with some epithelial cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells (two types of phagocytic cells that are derived from monocytes). The cortex is densely packed so it stains more intensely than the rest of the thymus (see [link] ). The medulla, where thymocytes migrate before leaving the thymus, contains a less dense collection of thymocytes, epithelial cells, and dendritic cells.

Thymic involution has been observed in all vertebrate species that have a thymus gland. Animal studies have shown that transplanted thymic grafts between inbred strains of mice involuted according to the age of the donor and not of the recipient, implying the process is genetically programmed. There is evidence that the thymic microenvironment, so vital to the development of naïve T cells, loses thymic epithelial cells according to the decreasing expression of the FOXN1 gene with age.

It is also known that thymic involution can be altered by hormone levels. Sex hormones such as estrogen and testosterone enhance involution, and the hormonal changes in pregnant women cause a temporary thymic involution that reverses itself, when the size of the thymus and its hormone levels return to normal, usually after lactation ceases. What does all this tell us? Can we reverse immunosenescence, or at least slow it down? The potential is there for using thymic transplants from younger donors to keep thymic output of naïve T cells high. Gene therapies that target gene expression are also seen as future possibilities. The more we learn through immunosenescence research, the more opportunities there will be to develop therapies, even though these therapies will likely take decades to develop. The ultimate goal is for everyone to live and be healthy longer, but there may be limits to immortality imposed by our genes and hormones.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Anatomy & Physiology' conversation and receive update notifications?