| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The new “frontiers” of European economic development in the immediate pre-industrial period 1500-1800 included tropical regions for plantation crops, such as sugar, tobacco, cotton, rice, indigo, and opium, and temperate zones for the cultivation and export of grains. The seagoing merchants of Portugal, France, Spain, Britain and the Netherlands trawled the islands of the East Indies for pepper and timber; established ports in India for commerce in silk, cotton and indigo; exchanged silver for Chinese tea and porcelain; traded sugar, tobacco, furs and rice in the Americas; and sailed to West Africa for slaves and gold. The slave trade and plantation economies of the Americas helped shift the center of global commerce from Asia to the Atlantic, while the new oceangoing infrastructure also allowed for the development of fisheries, particularly the lucrative whale industry. All these commercial developments precipitated significant changes in their respective ecosystems across the globe—deforestation and soil erosion in particular—albeit on a far smaller scale compared with what was to come with the harnessing of fossil fuel energy after 1800.

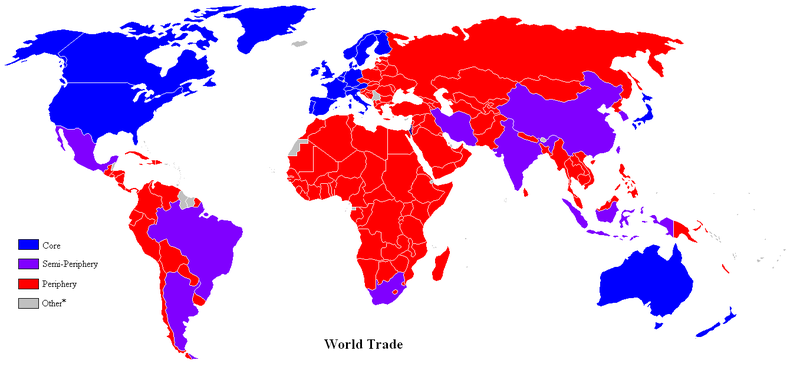

The 19 th century witnessed the most rapid global economic growth seen before or mostly since, built on the twin tracks of continued agricultural expansion and the new “vertical” frontiers of fossil fuel and mineral extraction that truly unleashed the transformative power of industrialization on the global community and its diverse habitats. For the first time since the human transition to agriculture more than 10,000 years before, a state’s wealth did not depend on agricultural yields from contiguous lands, but flowed rather from a variety of global sources, and derived from the industrialization of primary products, such as cotton textiles, minerals and timber. During this period, a binary, inequitable structure of international relations began to take shape, with a core of industrializing nations in the northern hemisphere increasingly exploiting the natural resources of undeveloped periphery nations for the purposes of wealth creation.

Despite the impact of the world wars and economic depression on global growth in the early 20 th century, the new technological infrastructure of the combustion engine and coal-powered electricity sponsored increased productivity and the sanitization of growing urban centers. Infectious diseases, the scourge of humanity for thousands of years, retreated, more than compensating for losses in war, and the world’s population continued to increase dramatically, doubling from 1 to 2 billion in 50 years, and with it the ecological footprint of our single species.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Sustainability: a comprehensive foundation' conversation and receive update notifications?