| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Bromine exists exclusively as bromide salts in the Earth’s crust, however, due to leaching, bromide salts have accumulated in sea water, but at a lower concentration than chloride. The majority of bromine is isolated from bromine-rich brines, which are treated with chlorine gas, flushing through with air. In this treatment, bromide anions are oxidized to bromine by the chlorine gas, [link] .

Two major sources of iodine are used for commercial production: the caliche (a hardened sedimentary deposit of calcium carbonate found in Chile) and the iodine containing brines of gas and oil fields in Japan and the United States. The caliche contains sodium nitrate (NaNO 3 ); in which traces of sodium iodate (NaIO 3 ) and sodium iodide (NaI) are found. During the production of sodium nitrate the sodium iodate and iodide is extracted. Iodine sourced from brine involves the acidification with sulfuric acid to form hydrogen iodide (HI), which is then oxidized to iodine with chlorine, [link] . The aqueous iodine solution is concentrated by passing air through the solution causing the iodine to evaporate. The iodine solution is then re-reduced with sulfur dioxide, [link] . The dry hydrogen iodide (HI) is reacted with chlorine to precipitate the iodine, [link] .

The physical properties of the halogens ( [link] ) encompasses gases (F 2 and Cl 2 ), a liquid (Br 2 ), a non-metallic solid (I 2 ), and a metallic metal (At).

| Element | Mp (°C) | Bp (°C) | Density (g/cm 3 ) |

| F | -219.62 | -188.12 | 1.7 x 10 -3 @ 0 °C, 101 kPa |

| Cl | -101.5 | -34.04 | 3.2 x 10 -3 @ 0 °C, 101 kPa |

| Br | -7.2 | 58.8 | 3.1028 (liquid) |

| I | 113.7 | 184.3 | 4.933 |

| At | 302 | 337 | ca . 7 |

All the halogens are highly reactive and are as a consequence of the stability of the X - ion are strong oxidizing agents ( [link] ).

| Reduction | Reduction potential (V) |

| F 2 + 2 e - → 2 F - | 2.87 |

| Cl 2 + 2 e - → 2 Cl - | 1.36 |

| Br 2 + 2 e - → 2 Br - | 1.07 |

| I 2 + 2 e - → 2 I - | 0.53 |

Chlorine gas, also known as bertholite , was first used as a weapon in World War I by Germany on April 22, 1915 in the Second Battle of Ypres. At around 5:00 pm on April 22, 1915, the German Army released one hundred and sixty eight tons of chlorine gas over a 4 mile front against French and colonial Moroccan and Algerian troops of the French 45 th and 78 th divisions ( [link] ). The attack involved a massive logistical effort, as German troops hauled 5730 cylinders of chlorine gas, weighing ninety pounds each, to the front by hand. The German soldiers also opened the cylinders by hand, relying on the prevailing winds to carry the gas towards enemy lines. Because of this method of dispersal, a large number of German soldiers were injured or killed in the process of carrying out the attack. Approximately 6,000 French and colonial troops died within ten minutes at Ypres, primarily from asphyxiation and subsequent tissue damage in the lungs. Many more were blinded. Chlorine gas forms hydrochloric acid when combined with water, destroying moist tissues such as lungs and eyes. The chlorine gas, being denser than air, quickly filled the trenches, forcing the troops to climb out into heavy enemy fire.

As described by the soldiers it had a distinctive smell of a mixture between pepper and pineapple. It also tasted metallic and stung the back of the throat and chest. The damage done by chlorine gas can be prevented by a gas mask, or other filtration method, making the fatalities from a chlorine gas attack much lower than those of other chemical weapons. The use as a weapon was pioneered by Fritz Haber ( [link] ) of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin, in collaboration with the German chemical conglomerate IG Farben, who developed methods for discharging chlorine gas against an entrenched enemy. It is alleged that Haber's role in the use of chlorine as a deadly weapon drove his wife, Clara Immerwahr, to suicide. After its first use, chlorine was used by both sides as a chemical weapon ( [link] ), but it was soon replaced by the more deadly gases phosgene and mustard gas.

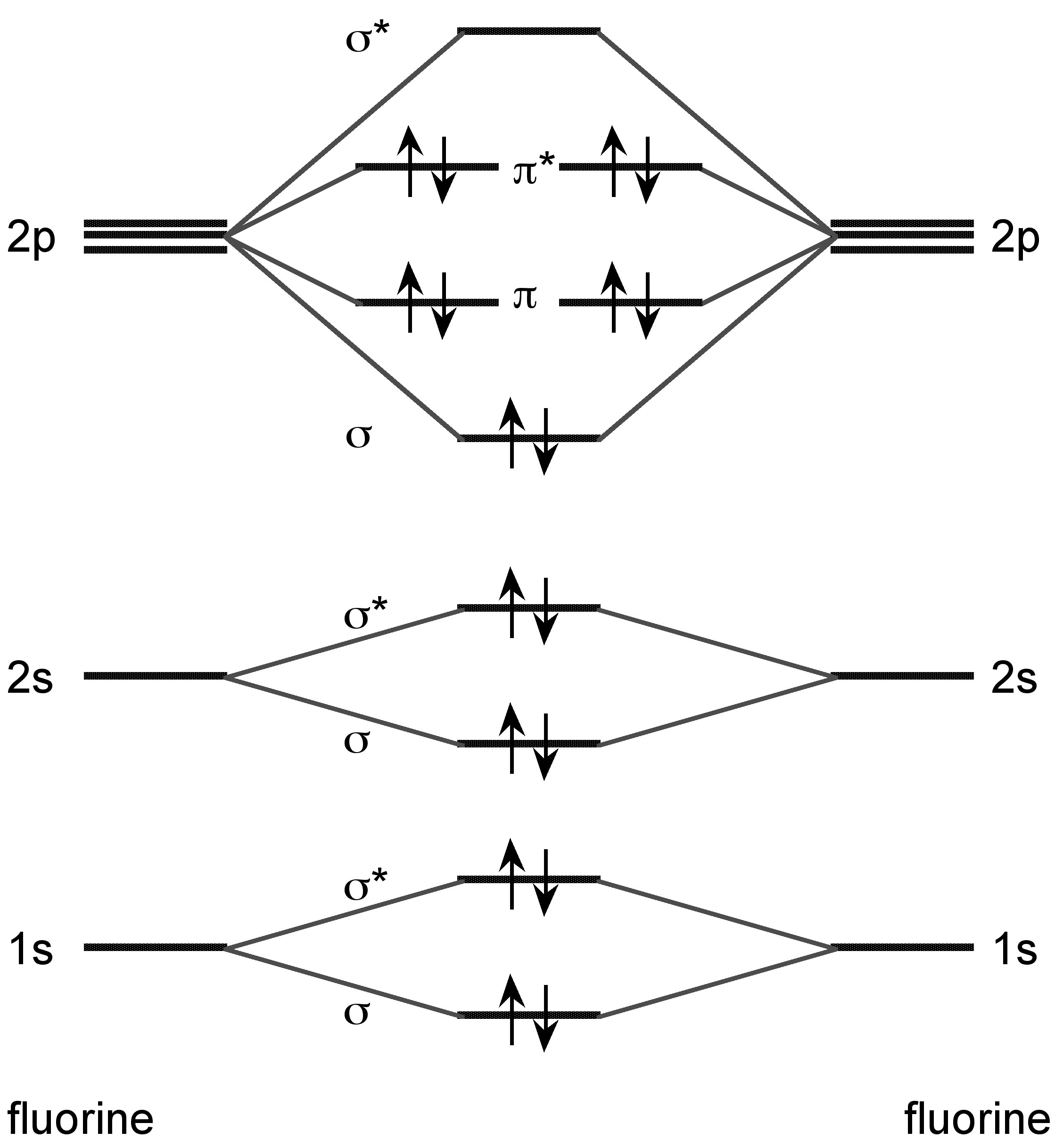

All the halogens form X 2 dimers in the vapor phase in an analogous manner to hydrogen. Unlike dihydrogen, however, the bonding is associated with the molecular orbital combination of the two p-orbitals ( [link] ). The bond lengths and energies are given in [link] .

| Element | Bond length (Å) | Energy (kJ/mol) |

| F 2 | 1.42 | 158 |

| Cl 2 | 1.99 | 243 |

| Br 2 | 2.29 | 193 |

| I 2 | 2.66 | 151 |

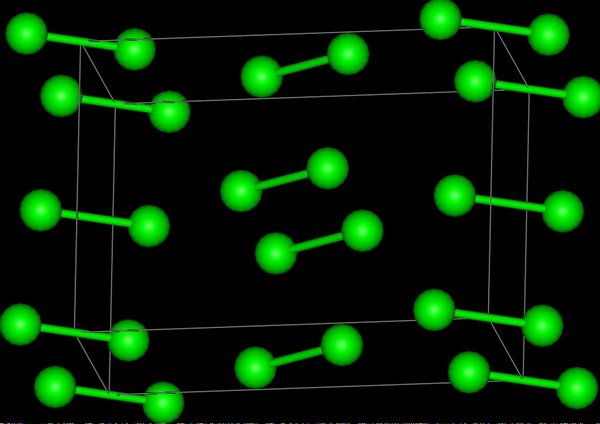

Iodine crystallizes in the orthorhombic space group Cmca ( [link] ). In the solid state, I 2 molecules still contain short I-I bond (2.70 Å).

The chemistry of the halogens is dominated by the stability of the -1 oxidation state and the noble gas configuration of the X - anion.

The use of oxidation state for fluorine is almost meaningless since as the most electronegative element, fluorine exists in the oxidation state of -1 in all its compounds, except elemental fluorine (F 2 ) where the oxidation state is zero by definition. Despite the general acceptance that the halogen elements form the associated halide anion (X - ), compounds with oxidation states of +1, +3, +4, +5, and +7 are common for chlorine, bromine, and iodine ( [link] ).

| Element | -1 | +1 | +3 | +4 | +5 | +7 |

| Cl | HCl | ClF | ClF 3 , HClO 2 | ClO 2 | ClF 5 , ClO 3 - | HClO 4 |

| Br | HBr | BrCl | BrF 3 | Br 2 O 4 | BrF 5 , BrO 3 - | BrO 4 - |

| I | HI | ICl | IF 3 , ICl 3 | I 2 O 4 | IO 3 - | IO 4 - |

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Chemistry of the main group elements' conversation and receive update notifications?