| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Market-oriented environmental policies create incentives to allow firms some flexibility in reducing pollution. The three main categories of market-oriented approaches to pollution control are pollution charges, marketable permits, and better-defined property rights. All of these policy tools, discussed below, address the shortcomings of command-and-control regulation—albeit in different ways.

A pollution charge is a tax imposed on the quantity of pollution that a firm emits. A pollution charge gives a profit-maximizing firm an incentive to figure out ways to reduce its emissions—as long as the marginal cost of reducing the emissions is less than the tax.

For example, consider a small firm that emits 50 pounds per year of small particles, such as soot, into the air. Particulate matter, as it is called, causes respiratory illnesses and also imposes costs on firms and individuals.

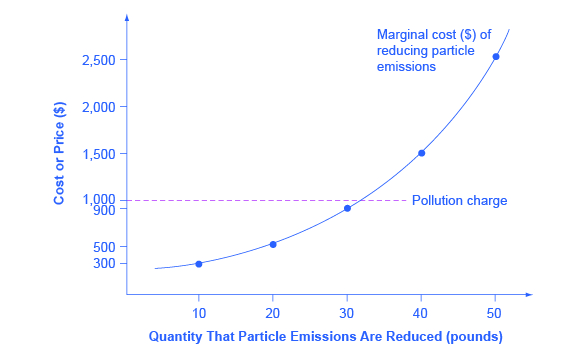

[link] illustrates the marginal costs that a firm faces in reducing pollution. The marginal cost of pollution reduction, like most most marginal cost curves increases with output, at least in the short run. Reducing the first 10 pounds of particulate emissions costs the firm $300. Reducing the second 10 pounds would cost $500; reducing the third ten pounds would cost $900; reducing the fourth 10 pounds would cost $1,500; and the fifth 10 pounds would cost $2,500. This pattern for the costs of reducing pollution is common, because the firm can use the cheapest and easiest method to make initial reductions in pollution, but additional reductions in pollution become more expensive.

Imagine the firm now faces a pollution tax of $1,000 for every 10 pounds of particulates emitted. The firm has the choice of either polluting and paying the tax, or reducing the amount of particulates they emit and paying the cost of abatement as shown in the figure. How much will the firm pollute and how much will the firm abate? The first 10 pounds would cost the firm $300 to abate. This is substantially less than the $1,000 tax, so they will choose to abate. The second 10 pounds would cost $500 to abate, which is still less than the tax, so they will choose to abate. The third 10 pounds would cost $900 to abate, which is slightly less than the $1,000 tax. The fourth 10 pounds would cost $1,500, which is much more costly than paying the tax. As a result, the firm will decide to reduce pollutants by 30 pounds, because the marginal cost of reducing pollution by this amount is less than the pollution tax. With a tax of $1,000, the firm has no incentive to reduce pollution more than 30 pounds.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of microeconomics for ap® courses' conversation and receive update notifications?