| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

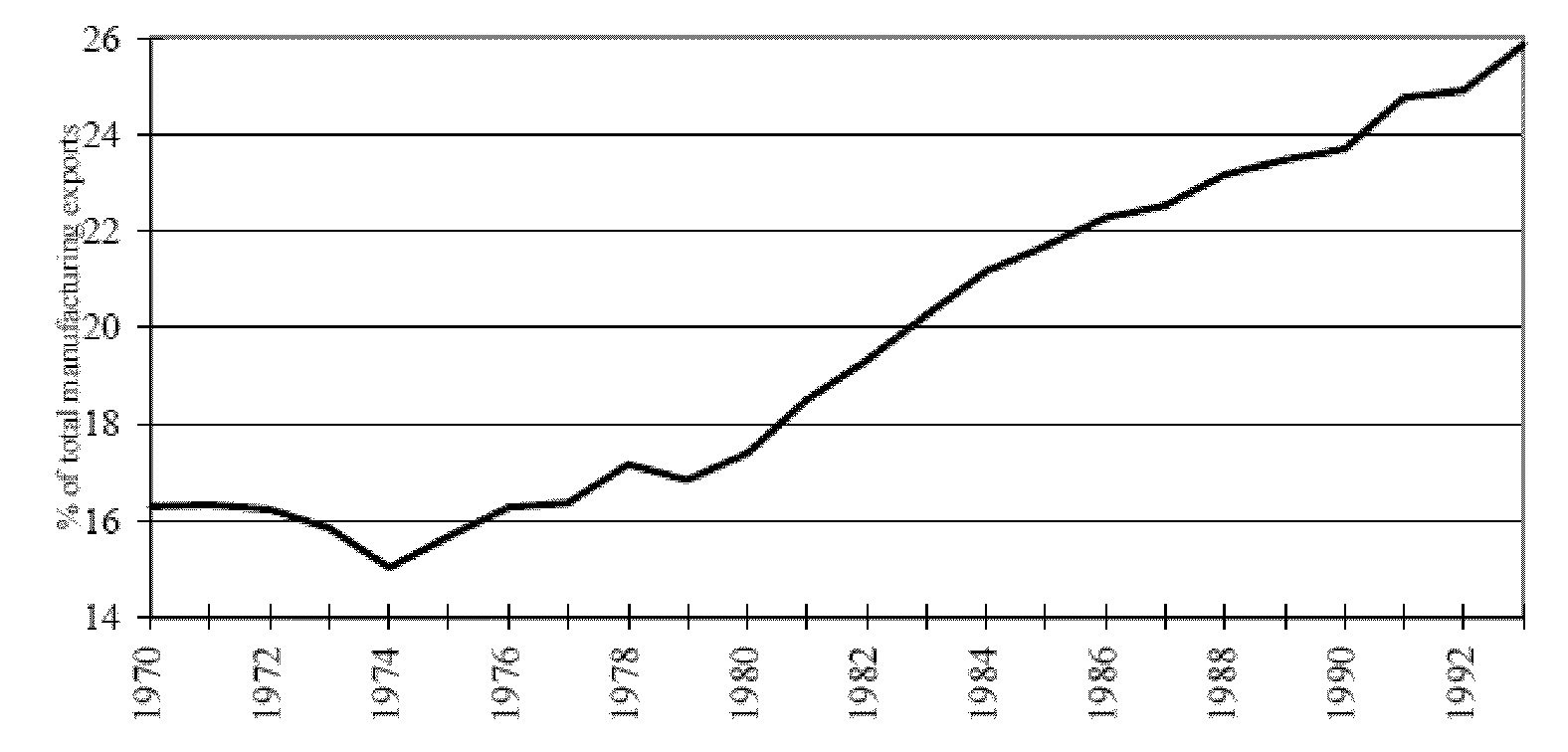

While much discussion has been made of the rise of the US Knowledge Economy during the 1990s (Porter and Stern 1999), the development of the Knowledge Economy has taken place throughout the world over a more significant timescale. This is shown in [link] where the increase in high-technology exports from all OECD nations has taken place since the end of the 1970s (OECD 1996).

The behaviour of economies has traditionally been studied in relation to the availability and application of production factors of labour, land, capital and natural resources. Economic growth has come from improvements in productivity of these factors, improved labour productivity (e.g., improved skills or longer hours), better use of land (e.g., larger farms), restructuring of industries (e.g., vertical integration) and technological change (e.g., the steam engine) or a combination thereof (Samuelson 1964). However, recent years have seen the emerging dominance of another production factor – knowledge. This also changes the way in which resources are considered for the most important ones are now created , rather than inherited (Porter 1990) This relates to creating competitive advantage at both the individual firm (Porter 1985) and national levels (Porter 1990). This is captured in the following observation by the World Bank (World Bank 1998):

“ For countries in the vanguard of the world economy, the balance between knowledge and resources has shifted so far towards the former that knowledge has become perhaps the most important factor determining the standard of living ”

Herein we examine the concept of the knowledge economy at the global, European, national and regional (Wales and South West Wales) levels.

In consideration of the Knowledge Economy it is useful to consider the core concept: knowledge itself. Traditional economic factors can be (relatively) easily defined and quantified. For example capital can be counted in pounds or dollars, land - in acres or hectares, labour (considered as a physical resource) – number of men (and women) and natural resources in volumes of reserves. There are of course other issues to consider regarding factors, such as quality (e.g., whether land is fertile or located in a useful position such as on a major river or coast, and purity of mineral resources).

However, each of the traditional resources is finite and subject to ‘ scarcity ’ whereby choices have to be made as to how they are to be applied (Samuelson 1964). Knowledge on the other hand is different in that it can be duplicated and disseminated. This means that value can often be exploited from the same instance of the resource several times. Doring and Shnellenbach (2006) provide a interesting study that investigates how this occurs, allowing growth that runs contrary to the traditional neoclassical economics suggestion that growth would only occur in step with the ‘stock’ of new knowledge. Furthermore, when knowledge is mixed with other knowledge further opportunities can be realised. This phenomenon is discussed in the context of ‘ Knowledge Spillovers ’ later in this section. Knowledge is also regarded as a public good and therefore monopolisation of its use is both difficult in terms of practicality and acceptability (World Bank 1999)

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'A study of how a region can lever participation in a global network to accelerate the development of a sustainable technology cluster' conversation and receive update notifications?