| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

NE binds to the beta-1 receptor. Some cardiac medications (for example, beta blockers) work by blocking these receptors, thereby slowing HR and are one possible treatment for hypertension. Overprescription of these drugs may lead to bradycardia and even stoppage of the heart.

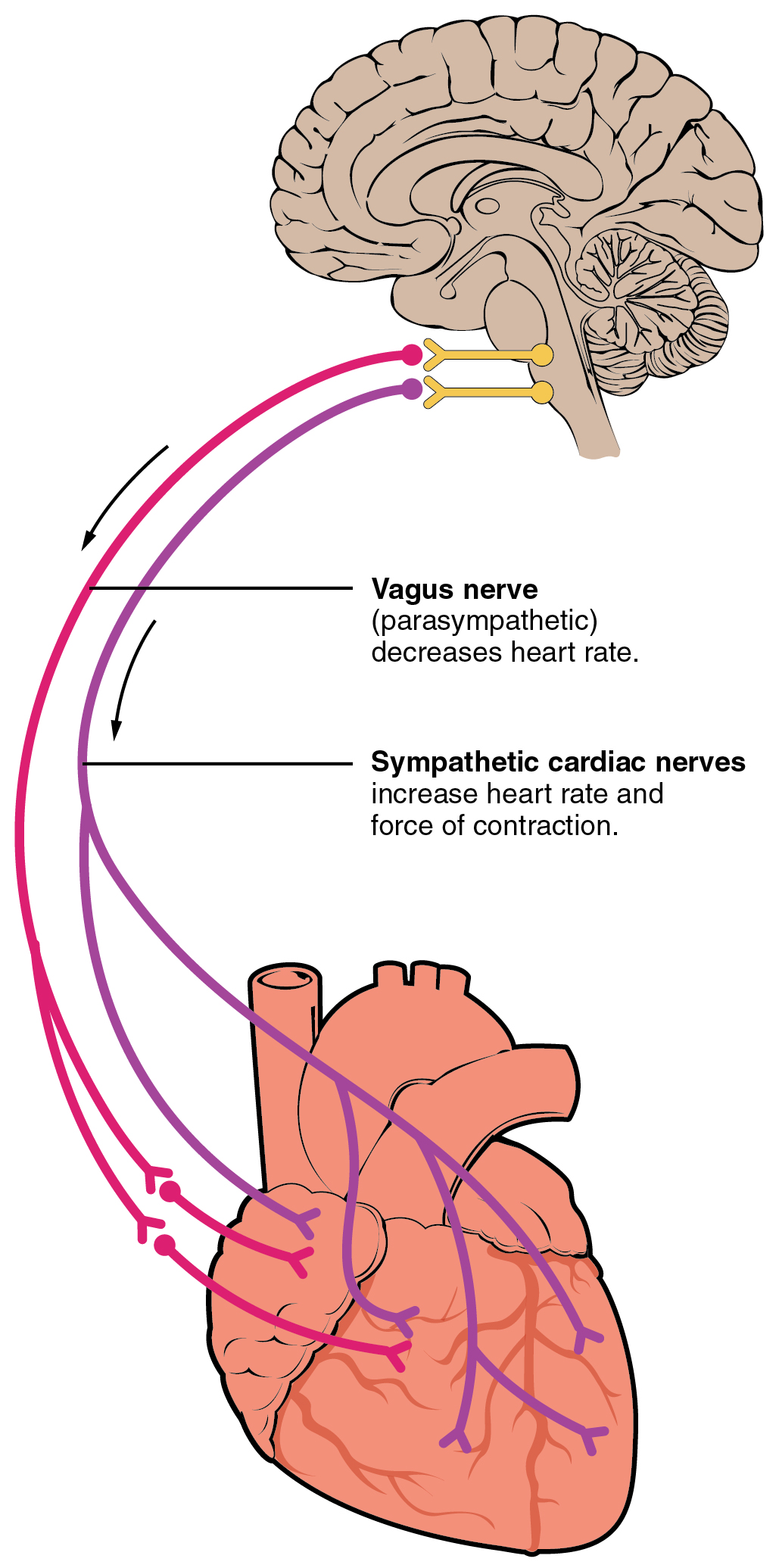

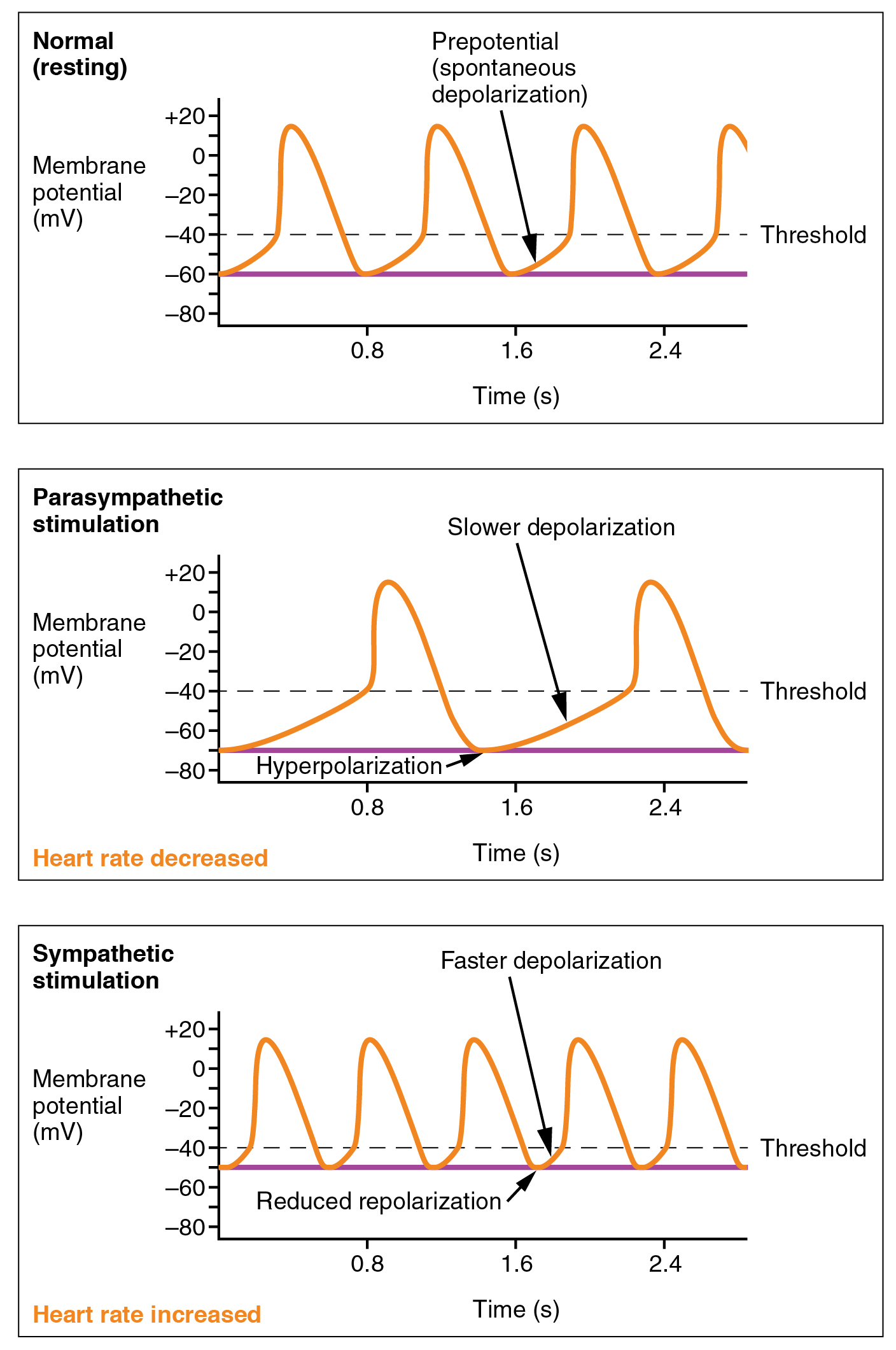

Parasympathetic stimulation originates from the cardioinhibitory region with impulses traveling via the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X). The vagus nerve sends branches to both the SA and AV nodes, and to portions of both the atria and ventricles. Parasympathetic stimulation releases the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) at the neuromuscular junction. ACh slows HR by opening chemical- or ligand-gated potassium ion channels to slow the rate of spontaneous depolarization, which extends repolarization and increases the time before the next spontaneous depolarization occurs. Without any nervous stimulation, the SA node would establish a sinus rhythm of approximately 100 bpm. Since resting rates are considerably less than this, it becomes evident that parasympathetic stimulation normally slows HR. This is similar to an individual driving a car with one foot on the brake pedal. To speed up, one need merely remove one’s foot from the break and let the engine increase speed. In the case of the heart, decreasing parasympathetic stimulation decreases the release of ACh, which allows HR to increase up to approximately 100 bpm. Any increases beyond this rate would require sympathetic stimulation. [link] illustrates the effects of parasympathetic and sympathetic stimulation on the normal sinus rhythm.

The cardiovascular center receives input from a series of visceral receptors with impulses traveling through visceral sensory fibers within the vagus and sympathetic nerves via the cardiac plexus. Among these receptors are various proprioreceptors, baroreceptors, and chemoreceptors, plus stimuli from the limbic system. Collectively, these inputs normally enable the cardiovascular centers to regulate heart function precisely, a process known as cardiac reflexes . Increased physical activity results in increased rates of firing by various proprioreceptors located in muscles, joint capsules, and tendons. Any such increase in physical activity would logically warrant increased blood flow. The cardiac centers monitor these increased rates of firing, and suppress parasympathetic stimulation and increase sympathetic stimulation as needed in order to increase blood flow.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Anatomy & Physiology' conversation and receive update notifications?