| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

An energetic cost may be incurred, as models of fish behavior show “burst and coast” swimming, where they perform a quick burst of energy followed by gliding, which appears to be the most energetically efficient form of swimming for fish. However, within a school this becomes virtually impossible as constant changes of velocity, direction, and synchrony must occur. Therefore, only if the energy saved by decreased anti-predatory behavior or increased foraging outweighs this energetic cost is schooling a valuable strategy (Fegelya et al).

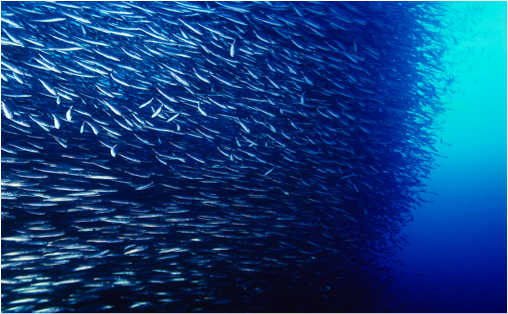

Because of the ability of schools to operate in unison and come together at important times, it seems obvious that there ought to be communication between fish. However, the ability of researchers to discern exactly how this communication occurs has been challenging and controversial. In 1887 studies proposed that fish use pheromones as alarm signals within the school, encouraging movement of the school away from a threat. Although this explanation was accepted for nearly a century, newer studies in minnows show no evidence of pheromones. Instead communication seems circumstantial and may be based upon learned behavioral cues, although it is still unclear how this may work (Magurran et al 1996). Modeling experiments show that individual movements within a school can change the direction and trajectory of the entire group, indicating that any individual can decide where the group should go (Romey 1996). In support of these models, guppies often school without an obvious leader, instead following movement cues of the neighbors to decide how to swim (Gungi 1998), which is also consistent with the ideal that neutral, attractive, and repulsive zones exist to direct spacing and movement inside the school. Additionally, it has been proposed that territorial cues such as boundaries, foraging sites, and danger zones also serve as signals for fish within the schools (Gungi1998). This behavioral signaling is extremely relevant because it indicates that schooling is much more complex than originally thought, and that many decisions are made as a group.

A new emerging area of study of schools has examined how human interactions with the environment and fish affect these schooling species. For example, it has been determined that the energetic costs of barriers, such as bridges, are larger than hypothesized because these barriers force the school to be manipulated in shape, changing the overall streamlined effect and demanding excessive energy input by each individual (Lemasson 2008). In terms of fishing, it has been seen that synthetic marine reserves increase the overall biomass of the fish, but decrease the number of catches due to increased schooling (Moustakas 2006). Additionally, another study warns that although fish populations do self regulate, and can increase reproduction in shrinking populations, excessive fishing can exploit this ability and actually irreparably damage a population (Bakun and Weeks 2006). Each of these studies reminds us that our knowledge of schools can be used for a variety of purposes, and this knowledge could help humans engage in more responsible development and fishing behavior in an effort to preserve the natural balance of fish in the wild.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Mockingbird tales: readings in animal behavior' conversation and receive update notifications?