| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

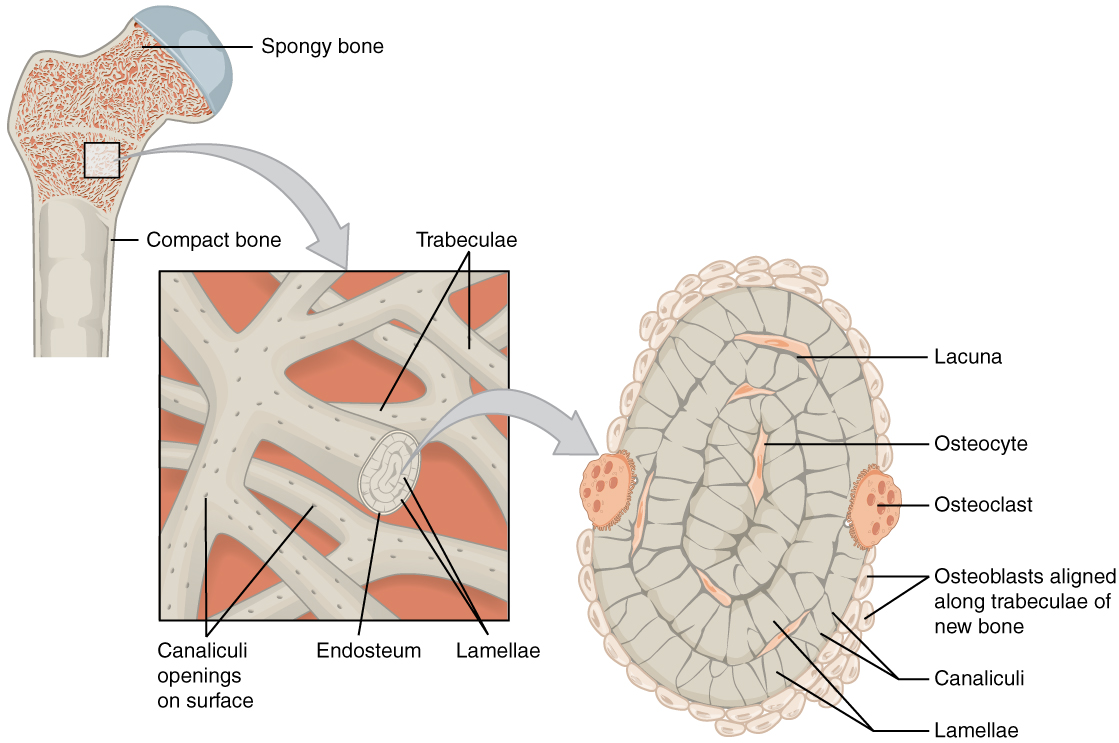

The osteoblast is the bone cell responsible for forming new bone and is found in the growing portions of bone, including the periosteum and endosteum. Osteoblasts, which do not divide, synthesize and secrete the collagen matrix and calcium salts. As the secreted matrix surrounding the osteoblast hardens, the osteoblast become trapped within it; as a result, it changes in structure and becomes an osteocyte This is the primary cell of mature bone and the most common type of bone cell. Each osteocyte is located in a space called a lacuna and is surrounded by bone tissue. Osteocytes maintain the mineral concentration of the matrix via the secretion of enzymes. They can communicate with each other and receive nutrients via long cytoplasmic processes that extend through canaliculi (singular = canaliculus), channels within the bone matrix.

Osteoblasts and osteocytes are incapable of mitosis or cell division, then how are they replenished when old ones die? The answer lies in the properties of a third category of bone cells—the osteogenic cell . These osteogenic cells are similar to stem cells and they are the only bone cells that divide. Immature osteogenic cells are found in the deep layers of the periosteum and the marrow. They differentiate and develop into osteoblasts.

The dynamic nature of bone means that new tissue is constantly formed, and old, injured, or unnecessary bone is dissolved for repair or for calcium release. The cell responsible for bone resorption, or breakdown, is the osteoclast . They are found on bone surfaces, are multinucleated, and originate from monocytes and macrophages, two types of white blood cells, not from osteogenic cells. Osteoclasts are continually breaking down old bone while osteoblasts are continually forming new bone. The ongoing balance between osteoblasts and osteoclasts is responsible for the constant but subtle reshaping of bone. [link] reviews the bone cells, their functions, and locations.

| Bone Cells | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cell type | Function | Location |

| Osteogenic cells | Develop into osteoblasts | Deep layers of the periosteum and the marrow |

| Osteoblasts | Bone formation | Growing portions of bone, including periosteum and endosteum |

| Osteocytes | Maintain mineral concentration of matrix | Entrapped in matrix |

| Osteoclasts | Bone resorption | Bone surfaces and at sites of old, injured, or unneeded bone |

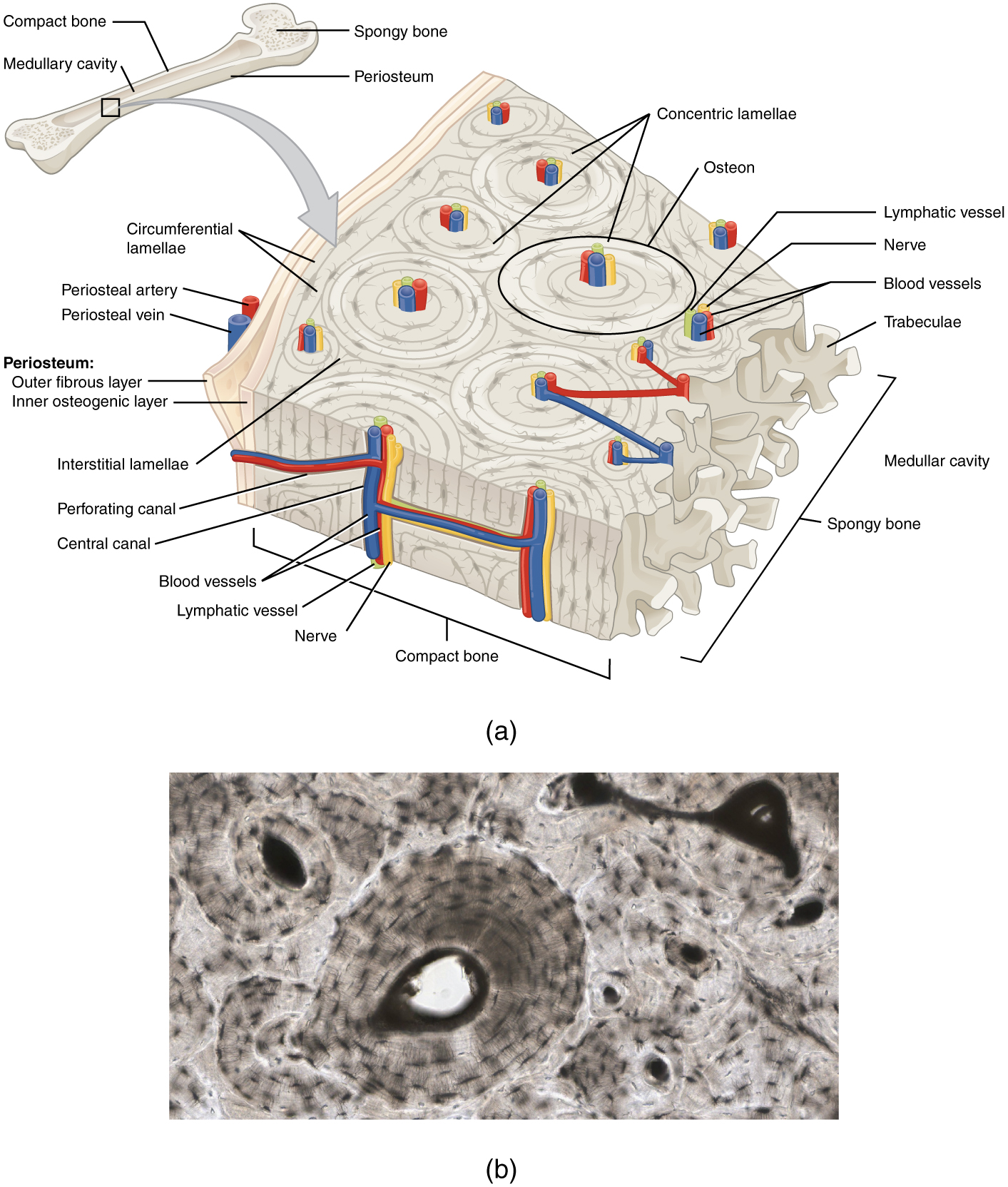

The differences between compact and spongy bone are best explored via their histology. Most bones contain compact and spongy osseous tissue, but their distribution and concentration vary based on the bone’s overall function. Compact bone is dense so that it can withstand compressive forces, while spongy or(cancellous) bone has open spaces and supports shifts in weight distribution.

Compact bone is the denser, stronger of the two types of bone tissue ( [link] ). It can be found under the periosteum and in the diaphyses of long bones, where it provides support and protection.

The microscopic structural unit of compact bone is called an osteon , or Haversian system. Each osteon is composed of concentric rings of calcified matrix called lamellae (singular = lamella). Running down the center of each osteon is the central canal , or Haversian canal, which contains blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels. These vessels and nerves branch off at right angles through a perforating canal , also known as Volkmann’s canals, to extend to the periosteum and endosteum.

The osteocytes are located inside spaces called lacunae (singular = lacuna), found at the borders of adjacent lamellae. As described earlier, canaliculi connect with the canaliculi of other lacunae and eventually with the central canal. This system allows nutrients to be transported to the osteocytes and wastes to be removed from them.

Like compact bone, spongy bone , also known as cancellous bone, contains osteocytes housed in lacunae, but they are not arranged in concentric circles. Instead, the lacunae and osteocytes are found in a lattice-like network of matrix spikes called trabeculae (singular = trabecula) ( [link] ). The trabeculae may appear to be a random network, but each trabecula forms along lines of stress to provide strength to the bone. The spaces of the trabeculated network provide balance to the dense and heavy compact bone by making bones lighter so that muscles can move them more easily. In addition, the spaces in some spongy bones contain red marrow, protected by the trabeculae, where blood cells are formed occurs.

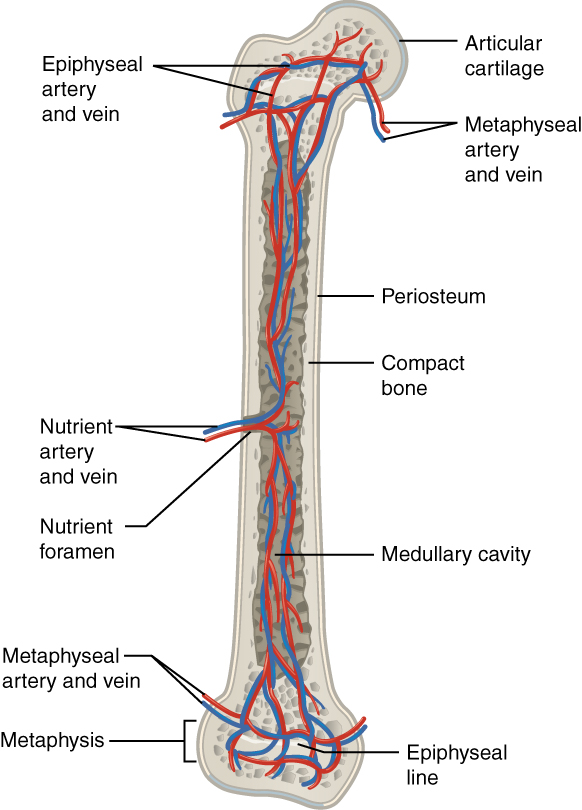

The spongy bone and medullary cavity receive nourishment from arteries that pass through the compact bone. The arteries enter through the nutrient foramen (plural = foramina), small openings in the diaphysis ( [link] ). The osteocytes in spongy bone are nourished by blood vessels of the periosteum that penetrate spongy bone and blood that circulates in the marrow cavities. As the blood passes through the marrow cavities, it is collected by veins, which then pass out of the bone through the foramina.

In addition to the blood vessels, nerves follow the same paths into the bone where they tend to concentrate in the more metabolically active regions of the bone. The nerves sense pain, and it appears the nerves also play roles in regulating blood supplies and in bone growth, hence their concentrations in metabolically active sites of the bone.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Skeletal system' conversation and receive update notifications?