| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

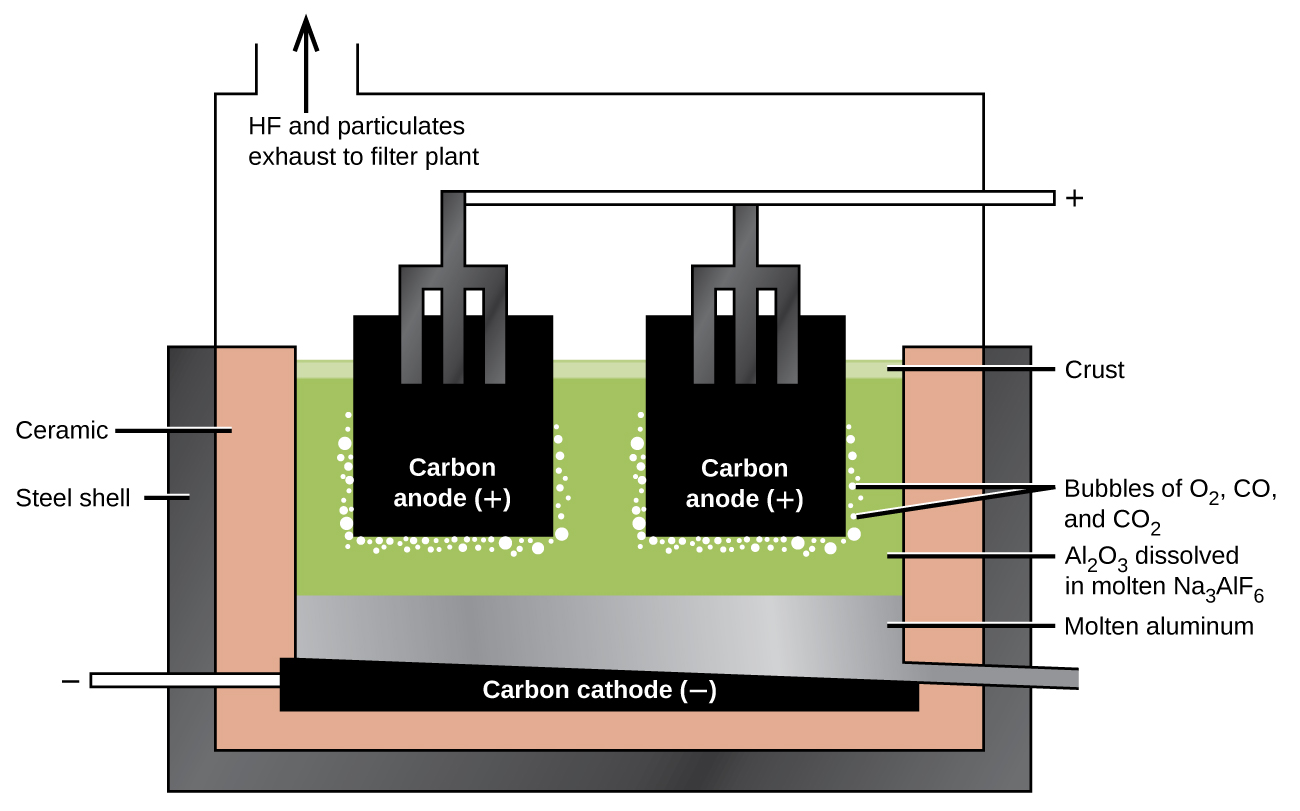

The preparation of aluminum utilizes a process invented in 1886 by Charles M. Hall , who began to work on the problem while a student at Oberlin College in Ohio. Paul L. T. Héroult discovered the process independently a month or two later in France. In honor to the two inventors, this electrolysis cell is known as the Hall–Héroult cell . The Hall–Héroult cell is an electrolysis cell for the production of aluminum. [link] illustrates the Hall–Héroult cell.

The production of aluminum begins with the purification of bauxite, the most common source of aluminum. The reaction of bauxite, AlO(OH), with hot sodium hydroxide forms soluble sodium aluminate, while clay and other impurities remain undissolved:

After the removal of the impurities by filtration, the addition of acid to the aluminate leads to the reprecipitation of aluminum hydroxide:

The next step is to remove the precipitated aluminum hydroxide by filtration. Heating the hydroxide produces aluminum oxide, Al 2 O 3 , which dissolves in a molten mixture of cryolite, Na 3 AlF 6 , and calcium fluoride, CaF 2 . Electrolysis of this solution takes place in a cell like that shown in [link] . Reduction of aluminum ions to the metal occurs at the cathode, while oxygen, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide form at the anode.

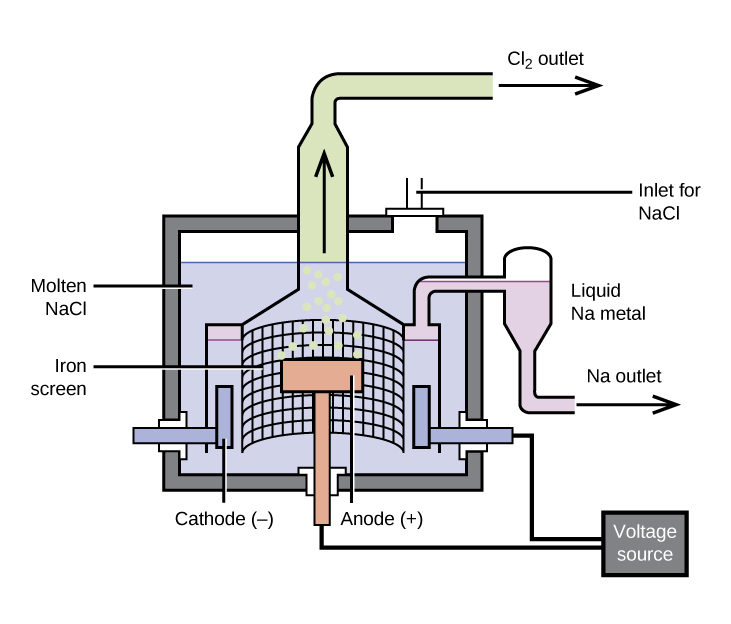

Magnesium is the other metal that is isolated in large quantities by electrolysis. Seawater, which contains approximately 0.5% magnesium chloride, serves as the major source of magnesium. Addition of calcium hydroxide to seawater precipitates magnesium hydroxide. The addition of hydrochloric acid to magnesium hydroxide, followed by evaporation of the resultant aqueous solution, leaves pure magnesium chloride. The electrolysis of molten magnesium chloride forms liquid magnesium and chlorine gas:

Some production facilities have moved away from electrolysis completely. In the next section, we will see how the Pidgeon process leads to the chemical reduction of magnesium.

It is possible to isolate many of the representative metals by chemical reduction using other elements as reducing agents. In general, chemical reduction is much less expensive than electrolysis, and for this reason, chemical reduction is the method of choice for the isolation of these elements. For example, it is possible to produce potassium, rubidium, and cesium by chemical reduction, as it is possible to reduce the molten chlorides of these metals with sodium metal. This may be surprising given that these metals are more reactive than sodium; however, the metals formed are more volatile than sodium and can be distilled for collection. The removal of the metal vapor leads to a shift in the equilibrium to produce more metal (see how reactions can be driven in the discussions of Le Châtelier’s principle in the chapter on fundamental equilibrium concepts).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Chemistry' conversation and receive update notifications?