| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

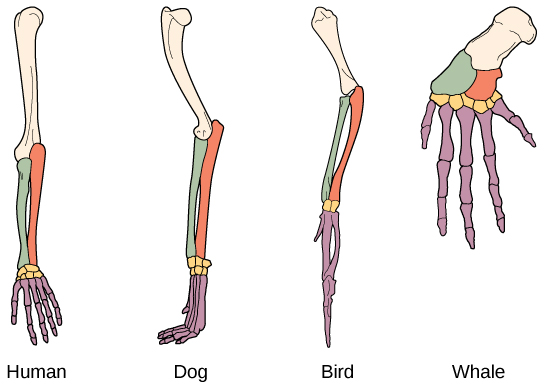

Click through the activities at this interactive site to guess which bone structures are homologous and which are analogous, and to see examples of all kinds of evolutionary adaptations that illustrate these concepts.

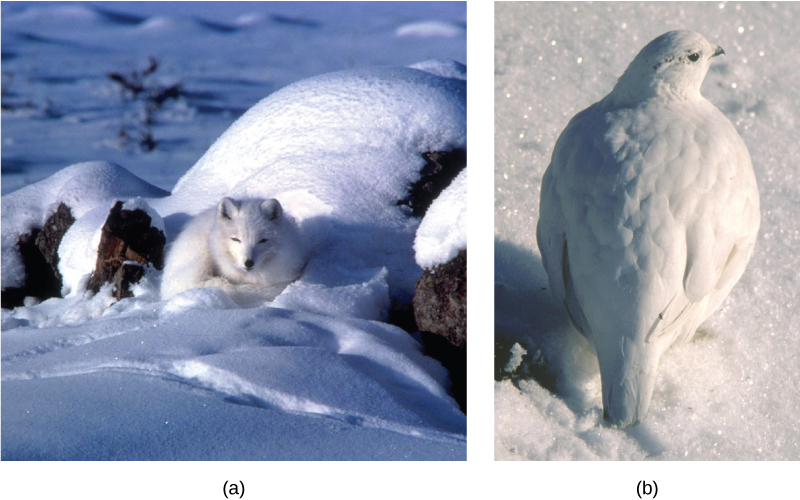

Another evidence of evolution is the convergence of form in organisms that share similar environments. For example, species of unrelated animals, such as the arctic fox and ptarmigan (a bird), living in the arctic region have temporary white coverings during winter to blend with the snow and ice ( [link] ). The similarity occurs not because of common ancestry, indeed one covering is of fur and the other of feathers, but because of similar selection pressures—the benefits of not being seen by predators.

Embryology, the study of the development of the anatomy of an organism to its adult form also provides evidence of relatedness between now widely divergent groups of organisms. Structures that are absent in some groups often appear in their embryonic forms and disappear by the time the adult or juvenile form is reached. For example, all vertebrate embryos, including humans, exhibit gill slits at some point in their early development. These disappear in the adults of terrestrial groups, but are maintained in adult forms of aquatic groups such as fish and some amphibians. Great ape embryos, including humans, have a tail structure during their development that is lost by the time of birth. The reason embryos of unrelated species are often similar is that mutational changes that affect the organism during embryonic development can cause amplified differences in the adult, even while the embryonic similarities are preserved.

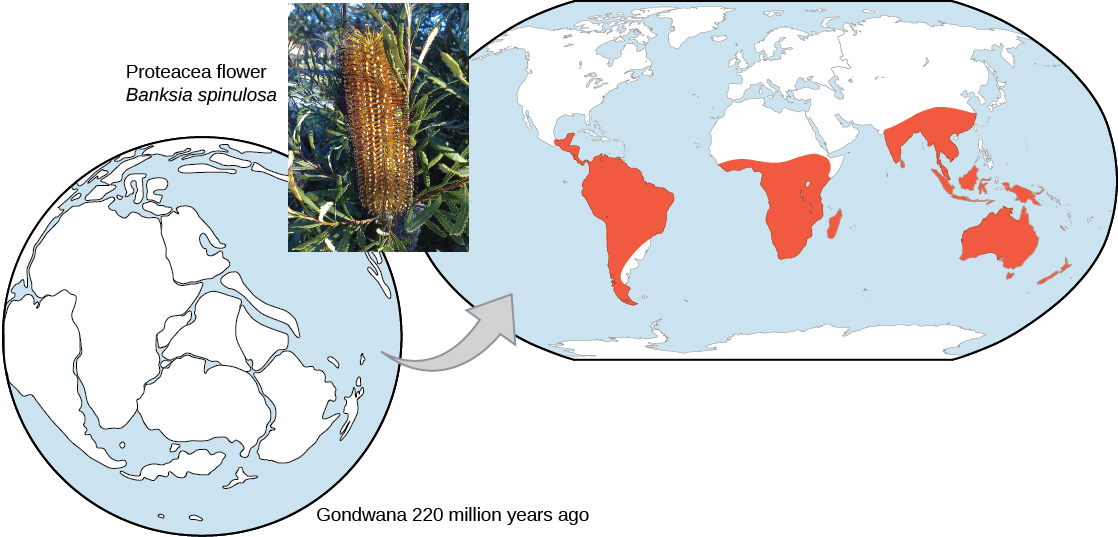

The geographic distribution of organisms on the planet follows patterns that are best explained by evolution in conjunction with the movement of tectonic plates over geological time. Broad groups that evolved before the breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea (about 200 million years ago) are distributed worldwide. Groups that evolved since the breakup appear uniquely in regions of the planet, for example the unique flora and fauna of northern continents that formed from the supercontinent Laurasia and of the southern continents that formed from the supercontinent Gondwana. The presence of Proteaceae in Australia, southern Africa, and South America is best explained by the plant family’s presence there prior to the southern supercontinent Gondwana breaking up ( [link] ).

The great diversification of the marsupials in Australia and the absence of other mammals reflects that island continent’s long isolation. Australia has an abundance of endemic species—species found nowhere else—which is typical of islands whose isolation by expanses of water prevents migration of species to other regions. Over time, these species diverge evolutionarily into new species that look very different from their ancestors that may exist on the mainland. The marsupials of Australia, the finches on the Galápagos, and many species on the Hawaiian Islands are all found nowhere else but on their island, yet display distant relationships to ancestral species on mainlands.

Like anatomical structures, the structures of the molecules of life reflect descent with modification. Evidence of a common ancestor for all of life is reflected in the universality of DNA as the genetic material and of the near universality of the genetic code and the machinery of DNA replication and expression. Fundamental divisions in life between the three domains are reflected in major structural differences in otherwise conservative structures such as the components of ribosomes and the structures of membranes. In general, the relatedness of groups of organisms is reflected in the similarity of their DNA sequences—exactly the pattern that would be expected from descent and diversification from a common ancestor.

DNA sequences have also shed light on some of the mechanisms of evolution. For example, it is clear that the evolution of new functions for proteins commonly occurs after gene duplication events. These duplications are a kind of mutation in which an entire gene is added as an extra copy (or many copies) in the genome. These duplications allow the free modification of one copy by mutation, selection, and drift, while the second copy continues to produce a functional protein. This allows the original function for the protein to be kept, while evolutionary forces tweak the copy until it functions in a new way.

The evidence for evolution is found at all levels of organization in living things and in the extinct species we know about through fossils. Fossils provide evidence for the evolutionary change through now extinct forms that led to modern species. For example, there is a rich fossil record that shows the evolutionary transitions from horse ancestors to modern horses that document intermediate forms and a gradual adaptation o changing ecosystems. The anatomy of species and the embryological development of that anatomy reveal common structures in divergent lineages that have been modified over time by evolution. The geographical distribution of living species reflects the origins of species in particular geographic locations and the history of continental movements. The structures of molecules, like anatomical structures, reflect the relationships of living species and match patterns of similarity expected from descent with modification.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Concepts of biology' conversation and receive update notifications?