| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The T H lymphocytes function indirectly to identify potential pathogens for other cells of the immune system. These cells are important for extracellular infections, such as those caused by certain bacteria, helminths, and protozoa. T H lymphocytes recognize specific antigens displayed in the MHC II complexes of APCs. There are two major populations of T H cells: T H 1 and T H 2. T H 1 cells secrete cytokines to enhance the activities of macrophages and other T cells. T H 1 cells activate the action of cyotoxic T cells, as well as macrophages. T H 2 cells stimulate naïve B cells to destroy foreign invaders via antibody secretion. Whether a T H 1 or a T H 2 immune response develops depends on the specific types of cytokines secreted by cells of the innate immune system, which in turn depends on the nature of the invading pathogen.

The T H 1-mediated response involves macrophages and is associated with inflammation. Recall the frontline defenses of macrophages involved in the innate immune response. Some intracellular bacteria, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis , have evolved to multiply in macrophages after they have been engulfed. These pathogens evade attempts by macrophages to destroy and digest the pathogen. When M. tuberculosis infection occurs, macrophages can stimulate naïve T cells to become T H 1 cells. These stimulated T cells secrete specific cytokines that send feedback to the macrophage to stimulate its digestive capabilities and allow it to destroy the colonizing M. tuberculosis . In the same manner, T H 1-activated macrophages also become better suited to ingest and kill tumor cells. In summary; T H 1 responses are directed toward intracellular invaders while T H 2 responses are aimed at those that are extracellular.

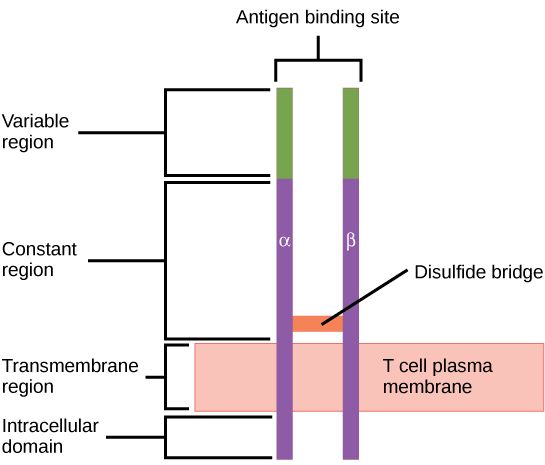

When stimulated by the T H 2 pathway, naïve B cells differentiate into antibody-secreting plasma cells. A plasma cell is an immune cell that secrets antibodies; these cells arise from B cells that were stimulated by antigens. Similar to T cells, naïve B cells initially are coated in thousands of B cell receptors (BCRs), which are membrane-bound forms of Ig (immunoglobulin, or an antibody). The B cell receptor has two heavy chains and two light chains connected by disulfide linkages. Each chain has a constant and a variable region; the latter is involved in antigen binding. Two other membrane proteins, Ig alpha and Ig beta, are involved in signaling. The receptors of any particular B cell, as shown in [link] are all the same, but the hundreds of millions of different B cells in an individual have distinct recognition domains that contribute to extensive diversity in the types of molecular structures to which they can bind. In this state, B cells function as APCs. They bind and engulf foreign antigens via their BCRs and then display processed antigens in the context of MHC II molecules to T H 2 cells. When a T H 2 cell detects that a B cell is bound to a relevant antigen, it secretes specific cytokines that induce the B cell to proliferate rapidly, which makes thousands of identical (clonal) copies of it, and then it synthesizes and secretes antibodies with the same antigen recognition pattern as the BCRs. The activation of B cells corresponding to one specific BCR variant and the dramatic proliferation of that variant is known as clonal selection . This phenomenon drastically, but briefly, changes the proportions of BCR variants expressed by the immune system, and shifts the balance toward BCRs specific to the infecting pathogen.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Biology' conversation and receive update notifications?