| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Contrast this with the situation today, when scientists rush to test each new hypothesis and do not accept any ideas until the results are in. For example, when two researchers at the University of Utah announced in 1989 that they had discovered a way to achieve nuclear fusion (the process that powers the stars) at room temperature, other scientists at more than 25 laboratories around the United States attempted to duplicate “cold fusion” within a few weeks—without success, as it turned out. The cold fusion theory soon went down in flames.

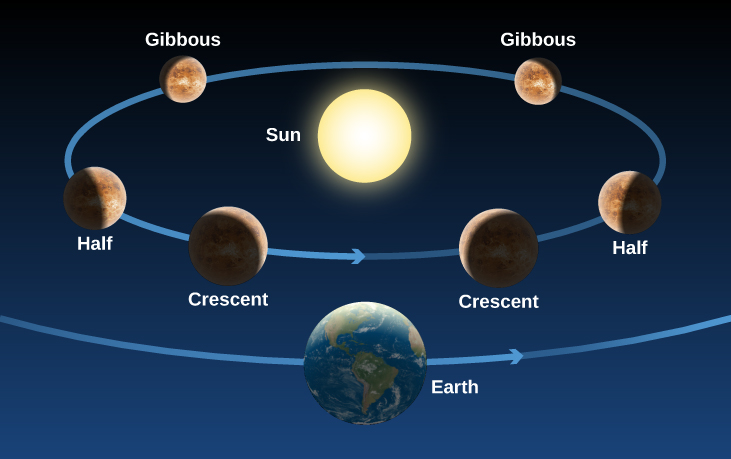

How would we look at Copernicus’ model today? When a new hypothesis or theory is proposed in science, it must first be checked for consistency with what is already known. Copernicus’ heliocentric idea passes this test, for it allows planetary positions to be calculated at least as well as does the geocentric theory. The next step is to determine which predictions the new hypothesis makes that differ from those of competing ideas. In the case of Copernicus , one example is the prediction that, if Venus circles the Sun, the planet should go through the full range of phases just as the Moon does, whereas if it circles Earth, it should not ( [link] ). Also, we should not be able to see the full phase of Venus from Earth because the Sun would then be between Venus and Earth. But in those days, before the telescope, no one imagined testing these predictions.

This animation shows the phases of Venus . You can also see its distance from Earth as it orbits the Sun.

Many of the modern scientific concepts of observation, experimentation, and the testing of hypotheses through careful quantitative measurements were pioneered by a man who lived nearly a century after Copernicus. Galileo Galilei ( [link] ), a contemporary of Shakespeare, was born in Pisa. Like Copernicus, he began training for a medical career, but he had little interest in the subject and later switched to mathematics. He held faculty positions at the University of Pisa and the University of Padua, and eventually became mathematician to the Grand Duke of Tuscany in Florence.

Galileo’s greatest contributions were in the field of mechanics, the study of motion and the actions of forces on bodies. It was familiar to all persons then, as it is to us now, that if something is at rest, it tends to remain at rest and requires some outside influence to start it in motion. Rest was thus generally regarded as the natural state of matter. Galileo showed, however, that rest is no more natural than motion.

If an object is slid along a rough horizontal floor, it soon comes to rest because friction between it and the floor acts as a retarding force. However, if the floor and the object are both highly polished, the object, given the same initial speed, will slide farther before stopping. On a smooth layer of ice, it will slide farther still. Galileo reasoned that if all resisting effects could be removed, the object would continue in a steady state of motion indefinitely. He argued that a force is required not only to start an object moving from rest but also to slow down, stop, speed up, or change the direction of a moving object. You will appreciate this if you have ever tried to stop a rolling car by leaning against it, or a moving boat by tugging on a line.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Astronomy' conversation and receive update notifications?