| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

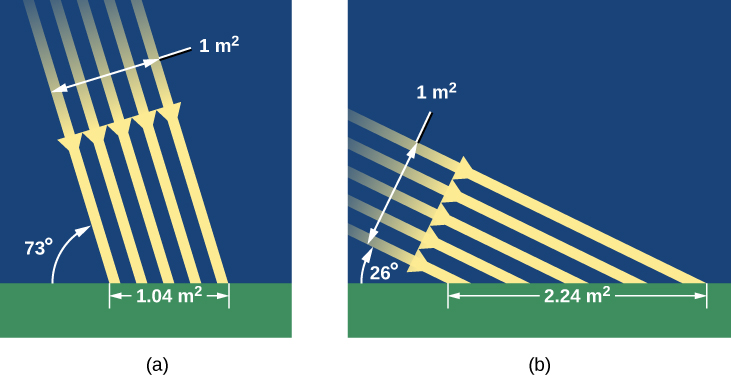

The second effect has to do with the length of time the Sun spends above the horizon ( [link] ). Even if you’ve never thought about astronomy before, we’re sure you have observed that the hours of daylight increase in summer and decrease in winter. Let’s see why this happens.

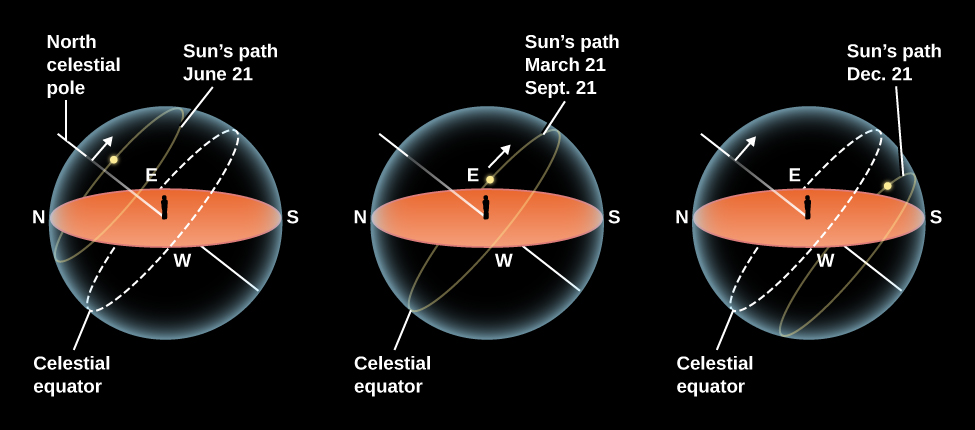

As we saw in Observing the Sky: The Birth of Astronomy , an equivalent way to look at our path around the Sun each year is to pretend that the Sun moves around Earth (on a circle called the ecliptic). Because Earth’s axis is tilted, the ecliptic is tilted by about 23.5° relative to the celestial equator (review [link] ). As a result, where we see the Sun in the sky changes as the year wears on.

In June, the Sun is north of the celestial equator and spends more time with those who live in the Northern Hemisphere. It rises high in the sky and is above the horizon in the United States for as long as 15 hours. Thus, the Sun not only heats us with more direct rays, but it also has more time to do it each day. (Notice in [link] that the Northern Hemisphere’s gain is the Southern Hemisphere’s loss. There the June Sun is low in the sky, meaning fewer daylight hours. In Chile, for example, June is a colder, darker time of year.) In December, when the Sun is south of the celestial equator, the situation is reversed.

Let’s look at what the Sun’s illumination on Earth looks like at some specific dates of the year, when these effects are at their maximum. On or about June 21 (the date we who live in the Northern Hemisphere call the summer solstice or sometimes the first day of summer), the Sun shines down most directly upon the Northern Hemisphere of Earth. It appears about 23° north of the equator, and thus, on that date, it passes through the zenith of places on Earth that are at 23° N latitude. The situation is shown in detail in [link] . To a person at 23° N (near Hawaii, for example), the Sun is directly overhead at noon. This latitude, where the Sun can appear at the zenith at noon on the first day of summer, is called the Tropic of Cancer .

We also see in [link] that the Sun’s rays shine down all around the North Pole at the solstice . As Earth turns on its axis, the North Pole is continuously illuminated by the Sun; all places within 23° of the pole have sunshine for 24 hours. The Sun is as far north on this date as it can get; thus, 90° – 23° (or 67° N) is the southernmost latitude where the Sun can be seen for a full 24-hour period (sometimes called the “land of the midnight Sun”). That circle of latitude is called the Arctic Circle .

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Astronomy' conversation and receive update notifications?