| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Until the early 1900s, astronomers generally accepted Herschel’s conclusion that the Sun is near the center of the Galaxy. The discovery of the Galaxy’s true size and our actual location came about largely through the efforts of Harlow Shapley . In 1917, he was studying RR Lyrae variable stars in globular clusters. By comparing the known intrinsic luminosity of these stars to how bright they appeared, Shapley could calculate how far away they are. (Recall that it is distance that makes the stars look dimmer than they would be “up close,” and that the brightness fades as the distance squared.) Knowing the distance to any star in a cluster then tells us the distance to the cluster itself.

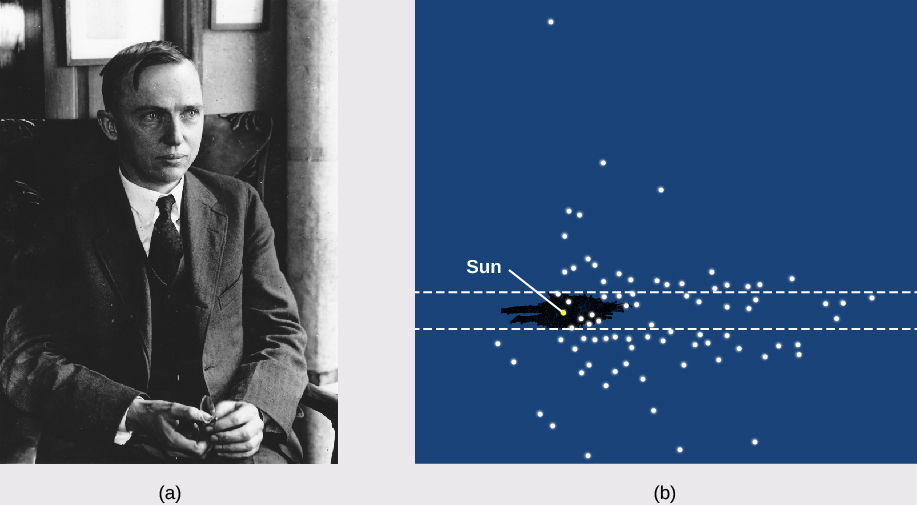

Globular clusters can be found in regions that are free of interstellar dust and so can be seen at very large distances. When Shapley used the distances and directions of 93 globular clusters to map out their positions in space, he found that the clusters are distributed in a spherical volume, which has its center not at the Sun but at a distant point along the Milky Way in the direction of Sagittarius. Shapley then made the bold assumption, verified by many other observations since then, that the point on which the system of globular clusters is centered is also the center of the entire Galaxy ( [link] ).

Shapley’s work showed once and for all that our star has no special place in the Galaxy. We are in a nondescript region of the Milky Way, only one of 200 to 400 billion stars that circle the distant center of our Galaxy.

Born in 1885 on a farm in Missouri, Harlow Shapley at first dropped out of school with the equivalent of only a fifth-grade education. He studied at home and at age 16 got a job as a newspaper reporter covering crime stories. Frustrated by the lack of opportunities for someone who had not finished high school, Shapley went back and completed a six-year high-school program in only two years, graduating as class valedictorian.

In 1907, at age 22, he went to the University of Missouri, intent on studying journalism, but found that the school of journalism would not open for a year. Leafing through the college catalog (or so he told the story later), he chanced to see “Astronomy” among the subjects beginning with “A.” Recalling his boyhood interest in the stars, he decided to study astronomy for the next year (and the rest, as the saying goes, is history).

Upon graduation Shapley received a fellowship for graduate study at Princeton and began to work with the brilliant Henry Norris Russell (see the Henry Norris Russell feature box). For his PhD thesis, Shapley made major contributions to the methods of analyzing the behavior of eclipsing binary stars. He was also able to show that cepheid variable stars are not binary systems, as some people thought at the time, but individual stars that pulsate with striking regularity.

Impressed with Shapley’s work, George Ellery Hale offered him a position at the Mount Wilson Observatory, where the young man took advantage of the clear mountain air and the 60-inch reflector to do his pioneering study of variable stars in globular clusters.

Shapley subsequently accepted the directorship of the Harvard College Observatory, and over the next 30 years, he and his collaborators made contributions to many fields of astronomy, including the study of neighboring galaxies, the discovery of dwarf galaxies, a survey of the distribution of galaxies in the universe, and much more. He wrote a series of nontechnical books and articles and became known as one of the most effective popularizers of astronomy. Shapley enjoyed giving lectures around the country, including at many smaller colleges where students and faculty rarely got to interact with scientists of his caliber.

During World War II, Shapley helped rescue many scientists and their families from Eastern Europe; later, he helped found UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. He wrote a pamphlet called Science from Shipboard for men and women in the armed services who had to spend many weeks on board transport ships to Europe. And during the difficult period of the 1950s, when congressional committees began their “witch hunts” for communist sympathizers (including such liberal leaders as Shapley), he spoke out forcefully and fearlessly in defense of the freedom of thought and expression. A man of many interests, he was fascinated by the behavior of ants, and wrote scientific papers about them as well as about galaxies.

By the time he died in 1972, Shapley was acknowledged as one of the pivotal figures of modern astronomy, a “twentieth-century Copernicus” who mapped the Milky Way and showed us our place in the Galaxy.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Astronomy' conversation and receive update notifications?