| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The fundamental insight that led to the formulation of the general theory of relativity starts with a very simple thought: if you were able to jump off a high building and fall freely, you would not feel your own weight. In this chapter, we will describe how Einstein built on this idea to reach sweeping conclusions about the very fabric of space and time itself. He called it the “happiest thought of my life.”

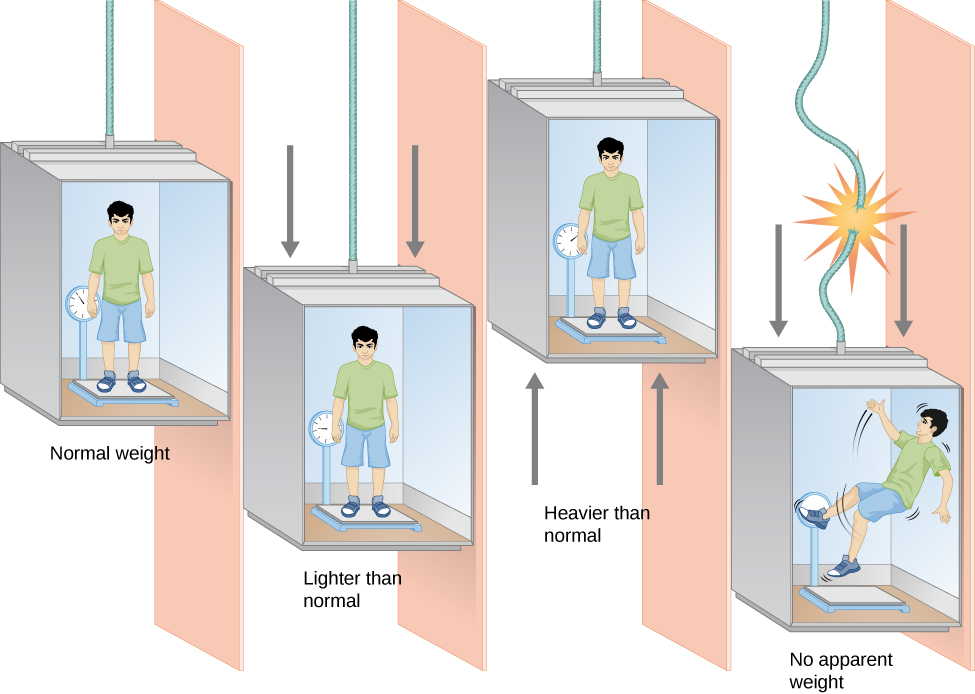

Einstein himself pointed out an everyday example that illustrates this effect (see [link] ). Notice how your weight seems to be reduced in a high-speed elevator when it accelerates from a stop to a rapid descent. Similarly, your weight seems to increase in an elevator that starts to move quickly upward. This effect is not just a feeling you have: if you stood on a scale in such an elevator, you could measure your weight changing (you can actually perform this experiment in some science museums).

In a freely falling elevator, with no air friction, you would lose your weight altogether. We generally don’t like to cut the cables holding elevators to try this experiment, but near-weightlessness can be achieved by taking an airplane to high altitude and then dropping rapidly for a while. This is how NASA trains its astronauts for the experience of free fall in space; the scenes of weightlessness in the 1995 movie Apollo 13 were filmed in the same way. (Moviemakers have since devised other methods using underwater filming, wire stunts, and computer graphics to create the appearance of weightlessness seen in such movies as Gravity and The Martian .)

Watch how NASA uses a “weightless” environment to help train astronauts.

Another way to state Einstein’s idea is this: suppose we have a spaceship that contains a windowless laboratory equipped with all the tools needed to perform scientific experiments. Now, imagine that an astronomer wakes up after a long night celebrating some scientific breakthrough and finds herself sealed into this laboratory. She has no idea how it happened but notices that she is weightless. This could be because she and the laboratory are far away from any source of gravity, and both are either at rest or moving at some steady speed through space (in which case she has plenty of time to wake up). But it could also be because she and the laboratory are falling freely toward a planet like Earth (in which case she might first want to check her distance from the surface before making coffee).

What Einstein postulated is that there is no experiment she can perform inside the sealed laboratory to determine whether she is floating in space or falling freely in a gravitational field. Strictly speaking, this is true only if the laboratory is infinitesimally small. Different locations in a real laboratory that is falling freely due to gravity cannot all be at identical distances from the object(s) responsible for producing the gravitational force. In this case, objects in different locations will experience slightly different accelerations. But this point does not invalidate the principle of equivalence that Einstein derived from this line of thinking. As far as she is concerned, the two situations are completely equivalent . This idea that free fall is indistinguishable from, and hence equivalent to, zero gravity is called the equivalence principle .

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Astronomy' conversation and receive update notifications?