| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

But all directions on a spinning sphere are not created equal. As the protostar rotates, it is much easier for material to fall right onto the poles (which spin most slowly) than onto the equator (where material moves around most rapidly). Therefore, gas and dust falling in toward the protostar’s equator are “held back” by the rotation and form a whirling extended disk around the equator (part b in [link] ). You may have observed this same “equator effect” on the amusement park ride in which you stand with your back to a cylinder that is spun faster and faster. As you spin really fast, you are pushed against the wall so strongly that you cannot possibly fall toward the center of the cylinder. Gas can, however, fall onto the protostar easily from directions away from the star’s equator.

The protostar and disk at this stage are embedded in an envelope of dust and gas from which material is still falling onto the protostar. This dusty envelope blocks visible light, but infrared radiation can get through. As a result, in this phase of its evolution, the protostar itself is emitting infrared radiation and so is observable only in the infrared region of the spectrum. Once almost all of the available material has been accreted and the central protostar has reached nearly its final mass, it is given a special name: it is called a T Tauri star , named after one of the best studied and brightest members of this class of stars, which was discovered in the constellation of Taurus. (Astronomers have a tendency to name types of stars after the first example they discover or come to understand. It’s not an elegant system, but it works.) Only stars with masses less than or similar to the mass of the Sun become T Tauri star s. Massive stars do not go through this stage, although they do appear to follow the formation scenario illustrated in [link] .

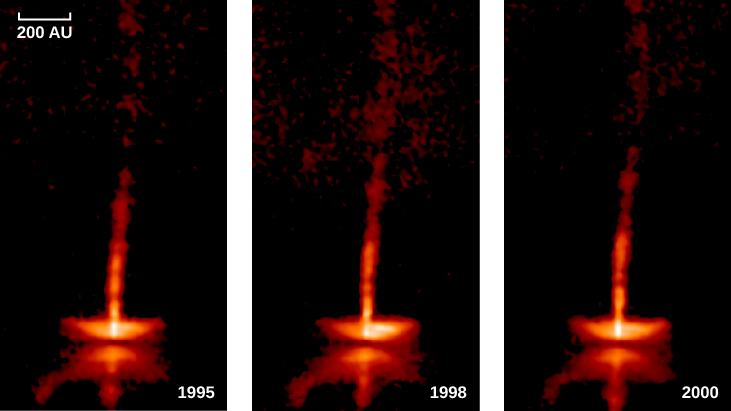

Recent observations suggest that T Tauri stars may actually be stars in a middle stage between protostars and hydrogen-fusing stars such as the Sun. High-resolution infrared images have revealed jets of material as well as stellar winds coming from some T Tauri stars, proof of interaction with their environment. A stellar wind consists mainly of protons (hydrogen nuclei) and electrons streaming away from the star at speeds of a few hundred kilometers per second (several hundred thousand miles per hour). When the wind first starts up, the disk of material around the star’s equator blocks the wind in its direction. Where the wind particles can escape most effectively is in the direction of the star’s poles.

Astronomers have actually seen evidence of these beams of particles shooting out in opposite directions from the popular regions of newly formed stars. In many cases, these beams point back to the location of a protostar that is still so completely shrouded in dust that we cannot yet see it ( [link] ).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Astronomy' conversation and receive update notifications?