| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Until the middle 1990s, the practical study of the origin of planets focused on our single known example—the solar system. Although there had been a great deal of speculation about planets circling other stars, none had actually been detected. Logically enough, in the absence of data, most scientists assumed that our own system was likely to be typical. They were in for a big surprise.

In The Birth of Stars and the Discovery of Planets outside the Solar System , we discuss the formation of stars and planets in some detail. Stars like our Sun are formed when dense regions in a molecular cloud (made of gas and dust) feel an extra gravitational force and begin to collapse. This is a runaway process: as the cloud collapses, the gravitational force gets stronger, concentrating material into a protostar. Roughly half of the time, the protostar will fragment or be gravitationally bound to other protostars, forming a binary or multiple star system—stars that are gravitationally bound and orbit each other. The rest of the time, the protostar collapses in isolation, as was the case for our Sun. In all cases, as we saw, conservation of angular momentum results in a spin-up of the collapsing protostar, with surrounding material flattened into a disk. Today, this kind of structure can actually be observed. The Hubble Space Telescope, as well as powerful new ground-based telescopes, enable astronomers to study directly the nearest of these circumstellar disks in regions of space where stars are being born today, such as the Orion Nebula ( [link] ) or the Taurus star-forming region.

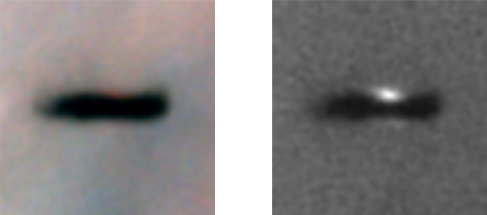

Many of the circumstellar disk s we have discovered show internal structure. The disks appear to be donut-shaped, with gaps close to the star. Such gaps indicate that the gas and dust in the disk have already collapsed to form large planets ( [link] ). The newly born protoplanets are too small and faint to be seen directly, but the depletion of raw materials in the gaps hints at the presence of something invisible in the inner part of the circumstellar disk—and that something is almost certainly one or more planets. Theoretical models of planet formation, like the one seen at right in [link] , have long supported the idea that planets would clear gaps as they form in disks.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Astronomy' conversation and receive update notifications?