| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Reflexes triggered by both chemical and neural stimuli control endocrine activity. These reflexes may be simple, involving only one hormone response, or they may be more complex and involve many hormones, as is the case with the hypothalamic control of various anterior pituitary–controlled hormones.

Humoral stimuli are changes in blood levels of non-hormone chemicals, such as nutrients or ions, which cause the release or inhibition of a hormone to, in turn, maintain homeostasis. For example, osmoreceptors in the hypothalamus detect changes in blood osmolarity (the concentration of solutes in the blood plasma). If blood osmolarity is too high, meaning that the blood is not dilute enough, osmoreceptors signal the hypothalamus to release ADH. The hormone causes the kidneys to reabsorb more water and reduce the volume of urine produced. This reabsorption causes a reduction of the osmolarity of the blood, diluting the blood to the appropriate level. The regulation of blood glucose is another example. High blood glucose levels cause the release of insulin from the pancreas, which increases glucose uptake by cells and liver storage of glucose as glycogen.

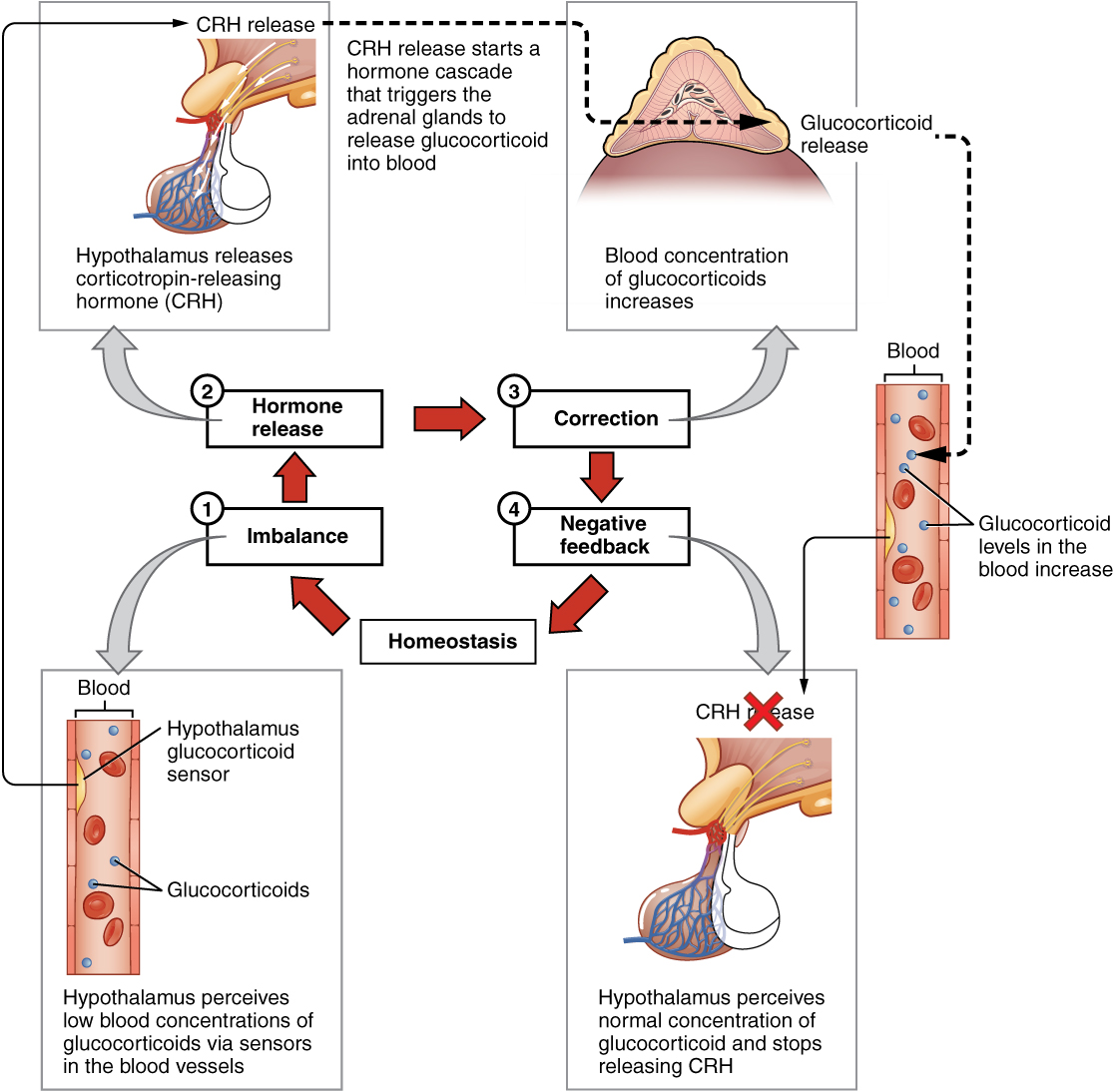

An endocrine gland may also secrete a hormone in response to the presence of another hormone produced by a different endocrine gland. Such hormonal stimuli often involve the hypothalamus, which produces releasing and inhibiting hormones that control the secretion of a variety of pituitary hormones.

In addition to these chemical signals, hormones can also be released in response to neural stimuli. A common example of neural stimuli is the activation of the fight-or-flight response by the sympathetic nervous system. When an individual perceives danger, sympathetic neurons signal the adrenal glands to secrete norepinephrine and epinephrine. The two hormones dilate blood vessels, increase the heart and respiratory rate, and suppress the digestive and immune systems. These responses boost the body’s transport of oxygen to the brain and muscles, thereby improving the body’s ability to fight or flee.

Research suggests that BPA is an endocrine disruptor, meaning that it negatively interferes with the endocrine system, particularly during the prenatal and postnatal development period. In particular, BPA mimics the hormonal effects of estrogens and has the opposite effect—that of androgens. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) notes in their statement about BPA safety that although traditional toxicology studies have supported the safety of low levels of exposure to BPA, recent studies using novel approaches to test for subtle effects have led to some concern about the potential effects of BPA on the brain, behavior, and prostate gland in fetuses, infants, and young children. The FDA is currently facilitating decreased use of BPA in food-related materials. Many US companies have voluntarily removed BPA from baby bottles, “sippy” cups, and the linings of infant formula cans, and most plastic reusable water bottles sold today boast that they are “BPA free.” In contrast, both Canada and the European Union have completely banned the use of BPA in baby products.

The potential harmful effects of BPA have been studied in both animal models and humans and include a large variety of health effects, such as developmental delay and disease. For example, prenatal exposure to BPA during the first trimester of human pregnancy may be associated with wheezing and aggressive behavior during childhood. Adults exposed to high levels of BPA may experience altered thyroid signaling and male sexual dysfunction. BPA exposure during the prenatal or postnatal period of development in animal models has been observed to cause neurological delays, changes in brain structure and function, sexual dysfunction, asthma, and increased risk for multiple cancers. In vitro studies have also shown that BPA exposure causes molecular changes that initiate the development of cancers of the breast, prostate, and brain. Although these studies have implicated BPA in numerous ill health effects, some experts caution that some of these studies may be flawed and that more research needs to be done. In the meantime, the FDA recommends that consumers take precautions to limit their exposure to BPA. In addition to purchasing foods in packaging free of BPA, consumers should avoid carrying or storing foods or liquids in bottles with the recycling code 3 or 7. Foods and liquids should not be microwave-heated in any form of plastic: use paper, glass, or ceramics instead.

Hormones are derived from amino acids or lipids. Amine hormones originate from the amino acids tryptophan or tyrosine. Larger amino acid hormones include peptides and protein hormones. Steroid hormones are derived from cholesterol.

Steroid hormones and thyroid hormone are lipid soluble. All other amino acid–derived hormones are water soluble. Hydrophobic hormones are able to diffuse through the membrane and interact with an intracellular receptor. In contrast, hydrophilic hormones must interact with cell membrane receptors. These are typically associated with a G protein, which becomes activated when the hormone binds the receptor. This initiates a signaling cascade that involves a second messenger, such as cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). Second messenger systems greatly amplify the hormone signal, creating a broader, more efficient, and faster response.

Hormones are released upon stimulation that is of either chemical or neural origin. Regulation of hormone release is primarily achieved through negative feedback. Various stimuli may cause the release of hormones, but there are three major types. Humoral stimuli are changes in ion or nutrient levels in the blood. Hormonal stimuli are changes in hormone levels that initiate or inhibit the secretion of another hormone. Finally, a neural stimulus occurs when a nerve impulse prompts the secretion or inhibition of a hormone.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Anatomy & Physiology' conversation and receive update notifications?